|

|

【中文标题】中印战争50周年:印度会和中国再次发生冲突吗?

【原文标题】The Sino-Indian War: 50 Years Later, Will India and China Clash Again?

【登载媒体】时代周刊

【原文作者】Ishaan Tharoor

【原文链接】http://world.time.com/2012/10/21/the-sino-indian-war-50-years-later-will-india-and-china-clash-again/

印度士兵在与中国的边境战争中。

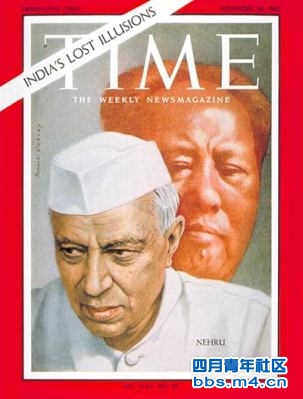

现代史上,印度和中国进行过唯一一场战争,它的结束就像开始一样突然。1962年10月20日,中国在多条战线突然发起攻势,打破了喜马拉雅冰川地带的宁静,摧毁了印度措手不及、武器落后的防线,印度士兵望风而逃。几天时间里,中国人在西面占领了克什米尔地区的阿克塞钦高原,东部逼近了印度主要茶叶种植区阿萨姆邦。到了11月21日,北京突然单方面停火,并从印度东北部撤军,但依然控制着贫瘠的阿克塞钦。《时代周刊》在1962年11月30日的封面报道中,洋洋得意地宣扬美国式和平:“红色中国在东方如此高深莫测的行事,让整个亚洲都困惑不解。”

五十年之后,依然有一些问题让人困惑不解:为什么本应尘封在19世纪档案中的领土纠纷,依然在困扰着21世界两个亚洲超级力量之间的关系。印中的经济纽带关系在不断强化,每年双边贸易额达700亿美元,这个数字在三年后将达到1000亿美元。但是,尽管进行了多次磋商,双方仍然没有解决延续了几十年、长达2100英里的边境线争端。那里依然是世界上最紧张的军事地带之一,这片遥远、多山的边境线还在在牵动着新德里和北京的紧张情绪。

争议的核心问题是麦克马洪线——由英国殖民政府与当时独立的西藏政府代表,在1914年划下的一条模糊、曲折的边境线。中国当然拒绝承认这条边境线,而是坚持声称拥有更久以前清朝地图所划定的领土。当时,满洲皇帝对西藏高原实施松散的宗主管理。1962年,不确定的历史、模糊的边境线,以及两个相对年轻的国家——毛的人民共和国和在尼赫鲁首相带领下刚独立的印度——导致中国对印度摧枯拉朽式的进攻。据统计,双方共有5000名士兵丧生。1962年,《时代周刊》把中国的进攻描述为“人海战术”,像“一群提着冲锋枪的红蚂蚁”。北京占领了一片“遍布白色石头的不毛之地”——阿克塞钦,从未归还,那里是连接西藏和中国西部地区新疆的战略要地。前印度外交官、新德里中国问题研究所荣誉会员基尚•拉纳说:“印中战争爆发的背景是一系列的误会。双方关系还在继续发展,边界尽管存在未解决的纠纷,但今天依然是平静的。”

然而,就像中国的经济改革未能使其政治制度彻底开放一样,印度和中国间强大的贸易关系也未能解开边界迷局。当前的边境或许相当“平静”,但近年来幕后暗流不断涌动。中国重申其对印度东北部省份阿鲁纳恰尔邦拥有全部主权,中国人在1962年占领该地,称其为“南西藏”,而印度也逐渐开始在长期以来不甚关注的东北部地区加强军事布署。西藏问题对印中关系影响深远。1959年,达赖喇嘛流亡到印度,北京至今对印度收容达赖一事耿耿于怀。最近,他来到阿鲁纳恰尔邦一座历史名寺中发表演讲,中国政府对此做出官方抗议。北京大学中印关系专家张华说:“印度和中国的领土纠纷中包含着西藏问题和国家尊严问题,整体局势相当复杂。双方总是不能用客观、理性的态度看待对方。”

民族主义的怨恨情绪不仅仅存在于国家权力核心的内部。皮尤全球项目在上周发布的一项调查结果显示,62%的中国人对印度持“不友好”态度。新德里政策研究中心的战略研究教授、美国人Brahma Chellaney的类似调查结果是48%,他担心这种情绪会影响北京的政治决策。在白热化的政治大环境中,中国领导层恐怕不能对强硬派民族主义者打击印度的呼声置之不理。Chellaney写道:

在印度看来,1962年的教训是,为了确保和平,就必须随时准备捍卫和平。中国嫉恶如仇的外交政策是双方关系紧张的根本原因,同时还有可能让北京禁不住给印度“第二次教训”,尤其是当第一次教训所获取的政治成果已经逐渐淡化的时候。中国的战略方针极为重视突袭和时机的选择,以图“速战速决”。如果中国再次发动闪电战,胜败将取决于一个关键因素:印度禁受首轮攻击的能力和绝地反击的决心。

中国在1962年之所以决定从其占领的大部分土地上撤军,主要是因为印度从英国和美国获得了大量的武器援助。华盛顿当时全神贯注处理古巴导弹危机,一些历史学家认为中国趁机发动了这次进攻。《时代周刊》1962年的封面文章对73岁的尼赫鲁痛加斥责——“他的头发雪白、稀疏,他的皮肤泛着灰色,眼神涣散。”他“用傲慢的态度无休止地〔教训〕西方,要与共产主义和平共处”。

亨利•鲁斯(译者注:著名的美国出版商,创办了《时代周刊》、《财富 (杂志)》与《生活》三大杂志)是个根深蒂固的冷战分子,他的《时代周刊》认为战争带给人们的教训,应当是尼赫鲁不结盟政策的消亡。所谓不结盟政策,是他与一些刚刚独立的国家共同采取的一种有原则的社会主义立场,不受美国和苏联的影响。《时代周刊》撰文称:“尼赫鲁头脑中永远挥之不去的念头是,共产主义也算是进步的象征,比‘帝国主义’对新兴国家造成的威胁要小。”他对亚洲团结一厢情愿的幻想,加上拒绝认可“印度真正的朋友”——也就是美国——带来了战争的羞辱。《时代周刊》在1962年的文章中毫不掩饰地希望印度军队为自身的权利,成为“一种政治力量的崛起”。对很多冷战中的美国人来说,与共产主义的伟大抗争,远比为一个羽翼未丰的民主国家的未来考虑重要得多。

与中国的战争恶化了尼赫鲁的身体状况,他在不到两年后去世。但是他对印度的贡献——民主——延续了下来,印度的军队——与邻国巴基斯坦需要与美国阵营更紧密结合的军队不同——避免了与印度政治同流合污的命运。

战争真正的遗留物并不是尼赫鲁愚蠢的理想,而是这片冰冻的土地:印度和中国这片纷扰的边境地带依然是这两个国家争执不休的牺牲品,在大规模军队的围困下奄奄一息。在西藏和新疆,任何异见动向和民族分裂主义分子都被无情打击。印度的克什米尔和东北部省份依然在实施非常时期的法律,即使是小小的选举权,也被几十年来的军队驻扎、禁欲式的管制和基础设施建设的严重不足所剥夺。《时代周刊》在1962年描述了阿萨姆邦的一条“吉普车道路”,70英里的路程走了18个小时。五十年后,印度东北部的状况并没有太多的改变。新德里曾经承诺要把这个地区转变成东南亚的经济中心,但迟迟未见行动。

大车队定期从曾经被称为拉达克的印度克什米尔出发,沿山路辗转而行,前往现在位于新疆境内的叶尔羌和和田,这早已成为久远的历史。拉萨的藏僧无法拜访位于印度东北区的佛教圣地。在新德里和北京冷酷对峙的局面下,印中边境居民生活所依赖的关系网络,以及真正的“世界屋脊”已经逐渐消失。阿鲁纳恰尔邦的一位下议院议员在今年年初对我说:“我们曾经有那么多共同之处,但都已经成为历史了。”

原文:

Indian troops training for the boarder war with China.

The only major war in modern history fought between India and China ended almost as abruptly as it began. On Oct. 20, 1962, a multi-pronged Chinese offensive burst the glacial stillness of the Himalayas and overwhelmed India’s unprepared and ill-equipped defenses, scattering its soldiers. Within days, the Chinese had wrested control of Kashmir’s Aksai Chin plateau in the west and, in the east, neared India’s vital tea-growing heartlands in Assam. Then, on Nov. 21, Beijing called a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew from India’s northeast, while keeping hold of barren Aksai Chin. TIME’s Nov. 30, 1962 cover story started off with a Pax Americana smirk: “Red China behaved in so inscrutably Oriental a manner last week that even Asians were baffled.”

Fifty years later, there are other reasons to be baffled: namely why a territorial spat that ought be consigned to dusty 19th century archives still rankles relations between the 21st century’s two rising Asian powers. Economic ties between India and China are booming: they share over $70 billion in annual bilateral trade, a figure that’s projected to reach as much as $100 billion in the next three years. But, despite rounds of talks, the two countries have yet to resolve their decades-old dispute over the 2,100-mile-long border. It remains one of the most militarized stretches of territory in the world, a remote, mountainous fault-line that still triggers tensions between New Delhi and Beijing.

At the core of the disagreement is the McMahon Line, an imprecise, meandering boundary drawn in 1914 by British colonial officials and representatives of the then independent Tibetan state. China, of course, refuses to recognize that line, and still refers much of its territorial claims to the maps and atlases of the long-vanished Qing dynasty, whose ethnic Manchu emperors maintained loose suzerainty over the Tibetan plateau. In 1962, flimsy history, confusion over the border’s very location and the imperatives of two relatively young states—Mao’s People’s Republic and newly independent India led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—led to China humiliating India in a crushing defeat where, by some accounts, nearly 5,000 soldiers died on both sides. In 1962, TIME described the Chinese offensive as a “human-sea assault,” like a “swarm of red ants” toting burp-guns. Beijing seized and has never relinquished Aksai Chin—”the desert of white stone”—a strategic corridor that links Tibet to the western Chinese region of Xinjiang. “The India-China war took place through a complex series of actions misunderstandings,” says Kishan S. Rana, a former Indian diplomat and honorary fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies in New Delhi. “Bilateral relations are, however, moving forward. The border, despite unresolved issues, today is a quiet border.”

Yet, just as China’s economic liberalization hasn’t led to an opening up of its political system, the strength of India and China’s trade ties have yet to unwind the border impasse. The border may be “quiet,” but tensions have spiked in recent years, with China reiterating its claim to almost the entirety of Arunachal Pradesh, a northeastern Indian state that the Chinese overran in 1962 and consider to be “Southern Tibet,” while India has steadily beefed up its military deployments in the long-neglected Northeast. The issue of Tibet casts a long shadow—in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India, an accommodation that Beijing still resents. When he went recently to speak at a historic monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, the Chinese government lodged a formal complaint. “The territorial dispute between India and China is intertwined with the Tibet issue and national dignity, making the whole situation more complicated,” says Zhang Hua, a Sino-Indian relations expert at Peking University. “When the two countries look at each other, they cannot see the counterparty in an objective and rational view.”

That nationalist ill-will is not just confined to those in the corridors of power. In a survey published last week, the Pew Global Attitudes Project found that 62% of Chinese hold an “unfavorable” view of India—compared to 48% feeling the same way of the U.S. Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, fears such sentiment driving the political calculus in Beijing. In a more heated climate, the Chinese leadership may not be immune to the calls of its more hardline nationalists to strike out at India, writes Chellaney:

For India, the haunting lesson of 1962 is that to secure peace, it must be ever ready to defend peace. China’s recidivist policies are at the root of the current bilateral tensions and carry the risk that Beijing may be tempted to teach India “a second lesson”, especially because the political gains of the first lesson have been frittered away. Chinese strategic doctrine attaches great value to the elements of surprise and good timing in order to wage “battles with swift outcomes.” If China were to unleash another surprise war, victory or defeat will be determined by one key factor: India’s ability to withstand the initial shock and awe and fight back determinedly.

China’s decision to withdraw from much of the territory it seized in 1962 was spurred by the arrival of significant amounts of aid and weaponry in India from the U.K. and the U.S.—Washington, at the time, was locked in the Cuban Missile Crisis, an imbroglio some historians suggest China exploited to its advantage in launching its assault. TIME’s 1962 cover story on the Sino-Indian war breathes fire on the 73-year-old Nehru—”his hair is snow-white and thinning, his skin greyish and his gaze abstracted”—and his “morally arrogant pose” of “endlessly [lecturing] the West on the need for peaceful coexistence with Communism.”

An inveterate Cold Warrior, Henry Luce’s TIME reckoned the chief lesson of the war ought to be the demise of Nehru’s policy of Nonalignment, his principled Socialist stand with a number of other recently independent states to chart a third path on the world stage, away from the influence of both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. (I’ve written about nonalignment at length here, here and here.) “Nehru has never been able to rid himself of that disastrous cliche that holds Communism to be somehow progressive and less of a threat to emergent nations than ‘imperialism,’” TIME declared. His dreamy belief in Asian solidarity and unwillingness to see who really were “India’s friends”—namely, the U.S.—led to India’s humiliation. Tellingly, the TIME 1962 story hopes for the Indian army to “emerge as something of a political force” in its own right—for many Americans during the Cold War, the grand struggle against Communism outranked any concern for the future of fledgling democracies.

The shock of the war with China is believed to have worsened Nehru’s health; he died less than two years later. But his gift to India—its democracy—has endured and its military—unlike that of neighboring Pakistan, which would be drawn much more firmly into the American camp—has avoided meddling in its politics.

The war’s real legacy lies less in the folly of Nehru’s ideals and more in the frozen landscape where the battles were fought: India and China’s restive borderlands remain the victim of the two countries’ longstanding dispute, locked down by vast military presences. In Tibet and Xinjiang, any trace of dissent or separatist ethnic nationalism is ruthlessly suppressed. In Indian Kashmir and in its northeastern states, emergency laws are still in effect—that small bonus of being able to vote somewhat dampened by decades of army occupation, woeful governance and inadequate investment in basic things like infrastructure. TIME, in 1962, described the journey down a “Jeep path” in Assam where it took 18 hours to cover 70 miles. Fifty years on, the conditions haven’t improved much in many parts of the Indian northeast; New Delhi’s belated efforts to transform the region into an economic hub with Southeast Asia have yet to take hold.

Long gone are the days when caravans would regularly depart from Ladakh, in what’s now Indian Kashmir, and wind their way around the mountains toward the Silk Road cities of Yarkhand and Khotan, now in Xinjiang. Tibetan monks in Lhasa can’t visit some of the most sacred sites of their faith that lie in the Indian northeast. The myriad connections that bound the communities living along the Indian-Chinese border, the veritable “roof of the world,” have been lost amid New Delhi and Beijing’s icy standoff. As one Member of Parliament from Arunachal Pradesh told me earlier this year, “There’s a lot we shared in common, but that’s now all a thing of the past.”

|

评分

-

1

查看全部评分

-

|