本帖最后由 满仓 于 2013-12-19 22:48 编辑

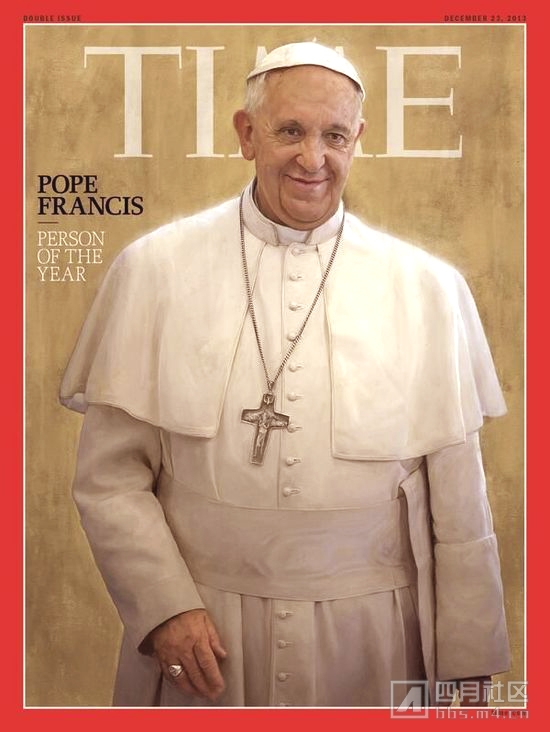

【中文标题】2013年度人物——教皇方济各

【原文标题】Pope Francis, The People’s Pope

【登载媒体】时代周刊

【原文作者】Howard Chua-Eoan、Elizabeth Dias

【原文链接】http://poy.time.com/2013/12/11/person-of-the-year-pope-francis-the-peoples-pope/

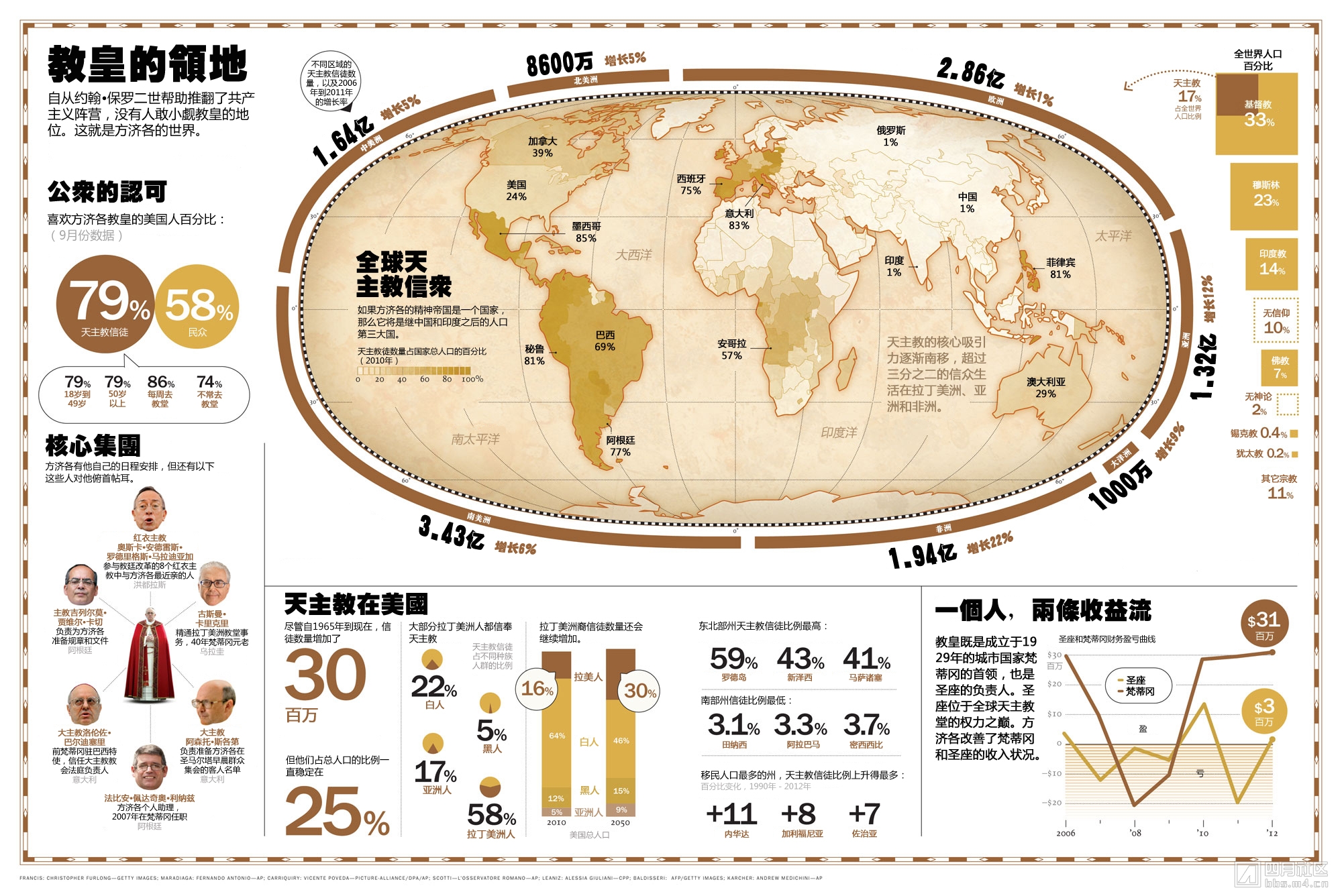

他以谦卑的圣徒之名,呼吁教堂成为疗伤的场所。1200年来第一任非欧洲裔的教皇,即将改变一个若干世纪以来死水一潭的地方。

在布宜诺斯艾利斯城市的边缘,有一条小小的街道,叫帕萨赫C区。这是一条泥泞、肮脏的小路,通往一个贫民窟,进而连接一条大路——马里诺阿科塔。帕萨赫的西班牙语意思是“通道”,尽头有一所教堂——纯真玛利亚堂。有一次,当地的牧师和几个惊恐万状的居民躲在圣堂里,几个贩毒帮派在外面火拼。穿过教堂,帕萨赫C区的小路延伸到其它地区:同样布满泥泞的车辙、水泥墙面剥落的帕萨赫A区到K区。用来建造临时住所的砖块堆满人行道,一所被焚毁的房子漆黑的墙面上潦草地喷着asesino(凶手),这所房屋在几天前因为报复一个枪击事件而被焚烧殆尽。几只狗趴在废弃的汽车下面,孩子们毫无顾忌地在路中间走来走去,因为汽车在这条坎坷不平的道路上开不了多快。但是,即使是帕萨赫C区也能通往罗马。

作为布宜诺斯艾利斯这座1350万人口的城市的红衣主教和大主教,豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥每年都会来到这个充满污秽和悲伤的地方,履行牧师巡游的职责。他从市中心的大教堂走到距离最近的地铁站,大教堂的柱子和穹顶完美体现了阿根廷的权威。他还经常一个人搭乘满是涂鸦的有轨电车去马里诺阿科塔,和其它地铁无法到达的地方。他徒步走完全程,拖着沉重的黑色矫正靴子进入帕萨赫C区。他有时还会来到城市其它的贫民窟,这样的地方实在太多了,但贫穷和肮脏从未阻止教堂巡游王子的脚步。“Reza por mí”,他向每一个见到的人打招呼,“为我祈祷”。

3月13日,贝尔高利奥继承了天堂之匙保管者圣彼得的王座,他向全世界发出了同样的声音。“为我祈祷。”他的辞职信——其中连带要求所有超过75岁的主教辞职——已经放在梵蒂冈的办公室里,等待最终批准。阿根廷的朋友们发现他的行动越来越迟缓,影响力不再。可突然之间,他脱胎换骨,称自己是追随阿西西圣徒的方济各。作为教皇,他是梵蒂冈的君主。他领导的这个机构如此庞大,信众数量超过中国人口;如此沉溺于传统的秩序,官僚风气横行;有如此广大的博爱心怀;丑闻重压之下如此狼狈;信奉教义的人的观点如此分化;教外之人看来如此神秘。这一切在他和天下穷苦大众之间划下了一道不可逾越的鸿沟——直到第266任罗马教皇穿着沉重的靴子走下宝座,自己掏钱支付酒店的费用。

教皇的职位既神秘又具有魔力,它把一个七十多岁的老者变成一个超级明星,却并没有透露他的任何个人信息。它在世界各个角落点燃了无法达成的希望,因为这些希望永远无法调和。年长的传统人士渴望老式的拉丁语弥撒,年轻的虔诚女性盼望成为牧师,他们都有希望。梵蒂冈教廷里野心勃勃的主教和远在菲律宾村庄里布道的执事也都有希望。任何教皇都无法取悦所有的人。

但是,让这位教皇与众不同的是,他迅速地捕捉到了数百万早已对教堂放弃希望的信众心中的想法。人们厌倦了无休止的性伦理讨论,以及争夺权力时相互推诿的内讧,与此同时(借用弥尔顿的话)“饥饿的绵羊抬起头,却没有食物”(译者注:语出《失乐园》)。在几个月时间里,方济各赋予教堂重要的疗伤任务——教堂以仆人和抚慰者的身份救助在残酷的现实世界中受伤的人们,这超越了他的前任所严格奉行的说教和监管责任。约翰•保罗二世和本笃十六世都曾经是神学院的教授,而方济各曾经是看门人、夜店保镖、化学剂师和文学教师。

在谦逊的外表之下,他是一个精明的管理者。他熟练地使用21世纪的工具运作1世纪的庞大机构。他给一个女性罪犯洗脚,与参观梵蒂冈的年轻人自拍,拥抱一个满脸长疣包的人。在谈到因为贫穷或遭受强奸而选择堕胎的问题,他说:“面对如此悲惨的遭遇,怎能有人不动容?”对于同性恋,他说:“如果有人是同性恋,而能怀善心追寻上帝,我有何资格论断?”对于离婚和再婚的天主教信徒按规定不能出席圣餐的问题,他说,重要的圣餐仪式“不是对完美的嘉奖,而是治疗伤痛的良药。”

这些话清醒、圆滑地传达了耶稣的旨意,就像福音书中的叙述。新教皇或许已经找到了走出20世纪文化战争的道路,这场战争让天主教堂在西欧大部分地区经营不善、奄奄一息,从都柏林到洛杉矶饱受批评。教皇这个职位的矛盾之处在于,一个新人的成功总是要背负前任教皇成功的辉煌。历史上沉重的教义和信条经过一个又一个世纪、一个又一个天才的积累,复杂地交织在一起,它们既是教皇权力的来源,也是限制其施展作为的桎梏。这些教条来自罗马的每一座雕像、每一个地窖、每一张手绘的古老卷轴,也来自世界各地的教堂、图书馆、医院、大学和博物馆。一个教皇要想施展自己的作为,必须遵循几个世纪以来被设定好的道路。

方济各虽然在用同样的答案回应一些尖锐的问题,但同时传达出伟大变革的信号。对于女性牧师的问题,他回答:“我们将会更加深入地研究女性神学体系。”意思就是,不。不可以堕胎,因为生命起始于怀孕。不赞成同性恋婚姻,因为男女结合是上帝的旨意。“教堂的教诲……很明确,我是教堂之子,但是”——他为自己祷告——“任何时候都不需要讨论这些问题。”

如果他的祷告可以得到回应,如果方济各可以通过自己活泼的个性让教堂与反对者和异见者形成一种崭新的关系——认可分裂教会的不同意见,更积极地从事散播仁爱的重要任务,那么他将会让世人看到自己辉煌的一面。“少说多做”是我们这个时代典型的治愈系格言,我们有太多的问题要面对了。方济各说,不要再争吵,卷起袖子做事情吧。不要让完美成为优秀的对立面——这个世界需要听到这样的话,尤其它是出自一个被世人认为没有缺点的人的口中。

数千人走上街头欢迎方济各每两周谒见信众的活动。

改变的教皇

这一任教皇开始于一个名字,豪尔赫•贝尔高利奥,是第一个选择13世纪穷人的守护神、阿西西的方济各作为自己名字的教皇。在十四世克莱门特、十六世本笃和二十一世约翰之后,这显然是个充满个人色彩的选择。据传说记载,13世纪的方济各皈依天主教,是因为听到耶稣受难像的呼唤,请他来修补上帝的房屋。他于是离开富有的丝绸生意家庭,与穷人住在一起。他是个和平倡导者,第一个进入埃及试图阻止十字军东征的天主教领袖。他把仁慈作为一生最重要的使命。

这个名字引出了方济各的很多行为。在本笃十六世看来,天主教堂是一种严格限定的精神药方,但方济各在接受耶稣会杂志《Civiltà Cattolica》编辑安东尼奥•斯帕德罗神父的采访时说,他认为“教堂就是战场上的医院”。这篇文章在9月期的杂志上发表。他眼中的教堂是田园式的、亲民的,而不是教条主义的,这将引导圣座把精力从如何吸引信众遥远的崇拜,转移到拥抱穷人、精神缺少寄托和孤独的人群上。他在288场宗座劝谕——又称为Evangelii gaudium(福音的喜乐)——中进一步扩展了他的思想。他写道:“我更喜欢一个破旧、残败、肮脏的教堂,因为这说明它被民众充分使用了,而不喜欢一个只为自身安全着想,被森严护卫的教堂。”他明确地表示不想谈更多,想要具体的改变。

他不再向牧师们授予崇高的主教头衔,以遏制追求名利的风气,而是更多地关注牧师们的布道。他告诉自己的使者,请他们在自己的国家物色大主教的人选。候选人必须“温和、耐心、仁慈、受内心贫穷情结所激励、体现主的自由、外表朴素、生活清贫”。在方济各看来,贫穷不仅仅关乎慈善,更关乎正义。教堂不仅仅代表罗马,也应当代表穷人。

这可以解释,为什么他把一度无人知晓的梵蒂冈施赈所——一个存在了800年的机构,一直供年老的天主教特使使用——交给充满活力的50岁波兰大主教康拉德•克拉约斯基,并告诉他把这个地方作为圣座的前厅。方济各告诉克拉约斯基:“你可以卖掉你的桌子,你不需要它。你应该走出梵蒂冈,别等人找上门来,你要主动出去接触穷人。”大主教给穷人发放了少量的救济,包括1600张电话卡,让一个沉船事故中幸存的移民可以打电话给厄立特里亚的家人。方济各经常给克拉约斯基几袋子信件,让他帮助这些给他写信的穷人。克拉约斯基曾经暗示,方济各有时候会打扮成普通人偷偷溜出梵蒂冈。梵蒂冈官方给予否认,这或许是个必要的预防措施。

方济各还亲自收拾梵蒂冈银行的烂摊子,美国财政部官员私下曾经表示,这家银行腐败问题严重。当选之后不久,他组建了一个委员会来彻底调查银行,这项工作最终落到一家独立审计公司身上。方济各还启动了反洗钱行动,严密监管梵蒂冈的财务状况。10月份,这家银行在其125年的历史上首次发布了年度财务报告。

在人事政策上,方济各忙得不可开交,他任新弃旧的行为撼动了整个教廷。彰显他严肃的用人态度的一件事是,弃用本笃的国务卿泰西修•贝尔托内,任命伯多禄•帕罗林为委内瑞拉大主教。这是继尤金尼奥•帕切利之后这个职位最年轻的人选,这个人在1939年成为教皇庇护十二世。

4月,方济各组建了一个小规模的会议,8名来自世界各地思想相近的大主教每年与他会面数次,梳理教会中的大问题。这一举动在某种程度上削减了传统上主教大会的权威。他在接受采访时说:“我不想举办象征性的讨论会,而是要实质性的讨论。”目前看来,他基本达到了这个目的。会议的成员说明了一切:来自智利、刚果、洪都拉斯、慕尼黑、澳大利亚和波士顿的红衣主教。8月,另一位成员,印度红衣主教奥斯瓦尔德•格拉西亚斯发表了天主教有史以来对待同性恋最开明的表态。他说尽管教堂不赞成同性恋婚姻,但同性恋不是罪。他在一封写给孟买LGBT(译者注:女同性恋、男同性恋、双性恋者、跨性别者英文首字母缩写)组织的信中说:“说其它性取向的人有罪是错误的。我们在布道和在公开场合讲话时必须严谨,我会通知我们的牧师。”

点击查看大图

12月5日,8人团体在酝酿了很久之后,任命了一个新的性虐案调查委员会,牧师侵犯儿童的事件让他们发誓要保护弱势群体的权利。这是在讲求存在的年代中,教堂最黑暗的存在主义问题。委员会的目的是研究保护儿童更好的方法、选择一些有关儿童的项目、建议创造安全环境的新方法、遴选负责这些项目的牧师。红衣主教们至少会为遍布世界各地的教区设立一个榜样,最好的结果是,他们承认梵蒂冈过于关注在法律层面挑战性虐待危机,而相对忽视了行为层面的问题。

方济各用他的布道和第一次宗座劝谕来支持他自己的行为。当他写道“为什么一个无家可归的老人在街头死去无法成为新闻,而股市下挫两点反而是新闻?”他简直无法控制自己的愤怒。在演讲中,他直接炮轰资本主义和全球化进程:“有些人依然在为涓滴经济理论辩护,这套理论认为自由市场竞争推动的经济增长,必然会给世界带来更大范围的正义和包容。这种观点……从未被实践印证过。”他说,教堂的工作必须“消除贫穷的结构性原因”,“教皇爱每一个人,无论贵贱,他以基督的名义有责任提醒富人,必须帮助、尊重穷人。”

教堂一贯把穷人作为自己的首要任务,这对于财政步履维艰的梵蒂冈来说是一个痛苦的两难选择。但方济各明确指出这是牧师的首要责任。他在5月份的演讲中说:“缺少警觉性,让牧师们半心半意、心不在焉、容易健忘,甚至颇不耐烦。吸引他们的是职业前景、金钱的诱惑和对世俗欲望的妥协。牧师变得懒惰,越来越像政府官员,只关心他自己和周围的组织结构,忘记了上帝子民的真善。”为了避免有人误解他的意思,他解除了德国林堡一位牧师的职务,这个人花费了4250万美元装修教堂的居室,其中包括一只价值2.05万美元的浴缸。贝尔高利奥的发言人吉列尔莫•马可说:“我们终于有了一个做过牧师的教皇。”

阿根廷的成长之路

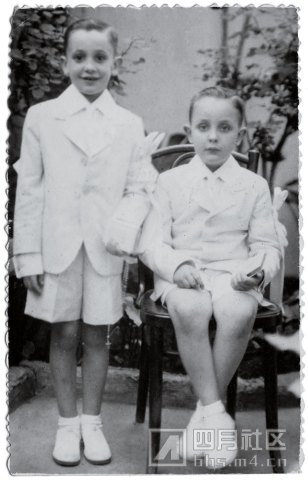

如果打算在布宜诺斯艾利斯度过一个周末,你可以参加一个3.5小时的汽车旅游,参观豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥长大的地方。汽车停在布宜诺斯艾利斯佛洛雷斯区的卡莱孟博里拉,导游问:“这是什么地方?”然后自己回答:“这是他的出生地。”他的父亲马里奥——意大利皮德蒙特人——和雷吉娜——皮埃蒙特的阿根廷后裔——1934年在这个小教堂相遇。他们次年结婚,在1936年12月17日生下第一个孩子豪尔赫•马里奥。

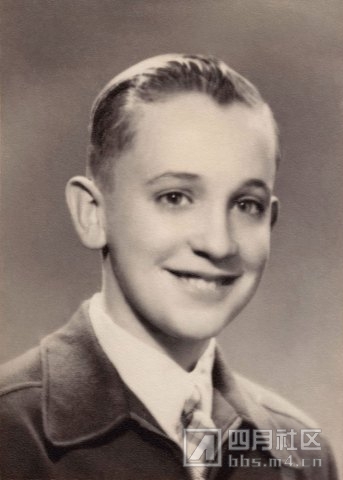

贝尔高利奥家族是虔诚的天主教信徒,是那种在教堂遇到未婚人士、社会主义者和美学家都要担心的人。但未来的教皇并不如此教条化,在他意识到自己即将成为一名牧师,和真正进入神学院之间的4年里,他说他“尽管没有超群的智慧,但还是有一些政治上的顾虑”。他承认自己喜欢阅读共产党的出版物,但从未加入共产党。一些贝尔高利奥观察人士——这在阿根廷已经形成了一个小小的产业——认为,他对于贫民的关注部分来源于阿根廷的庇隆主义运动。这是一种社会主义和资本主义思想奇怪的结合,40年代在这个国家兴起,根基是广大的工人阶级贫民。其意识形态渗透到阿根廷的每一个角落,直到现在。

对于职业选择,贝尔高利奥显得很神秘,一次和朋友们欢度假期的途中,他在一座教堂短暂停留。弗朗西斯卡•安布罗盖蒂和塞尔吉奥•鲁宾为在采访贝尔高利奥时,他说:“我极为震惊,一下子抛掉了所有的戒备。”他们的书《教皇方济各:与豪尔赫•贝尔高利奥的交谈》今年在美国出版。他对作者说,他直到1957年才进入神学院,“这就是我的宗教经历,竟然有人永远在那里等着和你见面。上帝打开一扇门,等了我几年。”

豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥(左)和他的弟弟奥斯卡在阿根廷布宜诺斯艾利斯。

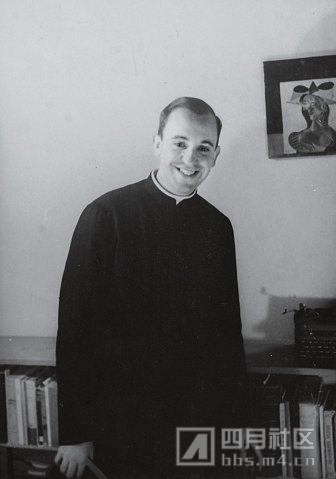

年轻的豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥

豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥(前排左二)在学校的戏剧节中穿着西装和领结,打扮成侍者的样子。

1966年,阿根廷神学院学生豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥在布宜诺斯艾利斯的萨尔瓦多学校教文学和心理学课程。

1998年豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥主教(中)在何塞•玛利亚•德宝拉和当地居民的陪同下,访问布宜诺斯艾利斯的贫民区。

2001年2月21日,在豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥荣升梵蒂冈红衣大主教之后,教皇约翰•保罗二世拥抱贝尔高利奥。

2005年3月24日,耶稣升天节,布宜诺斯艾利斯大主教、红衣主教豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥在萨尔达妇产医院为一名妇女洗脚。

2008年3月24日,豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥布宜诺斯艾利斯地铁车厢中与一位男人谈话。

2011年3月24日,红衣主教豪尔赫•马里奥•贝尔高利奥在布宜诺斯艾利斯举起圣罗伦佐足球队的小旗。

2013年3月14日,新当选的教皇方济各在罗马期间离开教堂提供的住所时,坚持自己支付费用,尽管这实际上就是他自己的产业。

他曾经是夜店的保镖,21岁在神学院学习时,右边的肺叶由于感染差点被切除,这或许是他现在背部经常疼痛的原因。他之所以加入耶稣会,是因为天主教堂发布的反改革法令要求“加入教堂的前线工作,严格遵守各项纪律”。他承认自己不大守规矩,因此需要一些约束。他与生俱来的天赋是同情心和与别人交谈的能力,在被授予牧师的圣职之前,他就非常受耶稣学校的学生和教会年长人士的欢迎。1937年,36岁的他在任职牧师3年之后,被任命为阿根廷耶稣会的会长。这个组织极富声望,承担着巨大的责任,而且给他的工作带来了长达二十年的动荡,几乎让他的职业生涯就此了结。

他的危机起始于两名耶稣会会士,奥兰多•尤里奥神父和弗朗西斯科•亚历克斯神父。在1975年初之后的一年时间里,他们拒绝执行命令离开贫民窟。当时国家陷入政治动乱,军方把贫民窟的牧师都当作反叛,而且已经有迹象要执掌阿根廷政权。无所不在的恐怖分子让国家分崩离析,很多阿根廷人,包括一些主教和牧师,都渴望有一个强大的势力重新执掌这个国家。因此很多人欢迎1976年3月24日的军事政变。

5月,两名耶稣会会士被捕,并遭到虐待。耶稣会人人痛苦万分,尤里奥(死于2000年)的家属至今还谴责贝尔高利奥放弃从军阀手中拯救牧师,他们当时提交了无数份文件,但官僚政府最终未能给贫民窟的牧师提供一个安全的庇护所。贝尔高利奥说他立即想办法让他们重获自由,尤里奥和亚历克斯在5个月之后被释放。很少有“消失”——阿根廷人管“绑架”叫做“消失”——的人重新出现。

即使当贝尔高利奥在1979年完成他的耶稣会会长任期之后,他依然是一个富有争议性的人物。1988年,他在布宜诺斯艾利斯的一所学校担任客座神学讲师,与当地大主教维克多•佐辛发生了矛盾,后者把贝尔高利奥安排到布宜诺斯艾利斯西北400英里的科尔多瓦去工作。据记者、方济各自传《生活和革命》一书的作者伊丽莎白•皮克描述,从1990年6月到1992年5月,他未经准许不能打电话,通信也被“控制”。佐辛说:“(贝尔高利奥)付出了巨大的代价接受这样的变化,但痛苦让他成长。”

幸运的转折点到来了,一名红衣主教非常欣赏贝尔高利奥的工作,也赞赏他擅于用人、组织高效会议的能力。他找到他,把他带出科尔多瓦这个流放地,并且推动他在教堂的等级阶层中扶摇直上。他从主教升为大主教,进而升为红衣主教,贝尔高利奥从未离开贫民窟,也就是尤里奥和亚历克斯拒绝离开的那种地方。亚历克斯现在住在巴伐利亚,四十年来他对这件事一直保持沉默。贝尔高利奥荣膺方济各之后,他发表了一份声明,说:“豪尔赫•贝尔高利奥从未抛弃过奥兰多•尤里奥和我……我曾经以为我们是民众口诛笔伐的受害者。但在90年代末期,了解很多事实真相之后,很明显我错了。”

1988年晋升为大主教之后,贝尔高利奥以简朴的生活方式出名。他出行的方式一般是公共汽车和地铁,住在教堂附近的简陋公寓中,而没有搬到教区的豪华住宅里。谦逊的态度不但赢得了普通阿根廷民众的欢迎,也感染了拉丁美洲其他大主教。他在流放之后令人眼花缭乱的晋升在2005年4月似乎达到了顶峰,约翰•保罗二世的去世让他来到罗马,进入了梵蒂冈史学家们所谓的papabili——教皇候选人——名单中。德国籍红衣主教若瑟•拉青格被选为教皇本笃十六世之后的一个星期三,贝尔高利奥与他的新闻秘书马可一起吃午餐。据马可叙述,他从未透露作为一名拉美裔红衣主教,他赢得的选票让他在教皇选举会议中排名第二。有人说,贝尔高利奥建议他的支持者把选票投给拉青格,以避免拖延选举过程,给外界造成教派内部意见不一致的印象。

他回到布宜诺斯艾利斯准备退休。他已经选好了度过余生的地方——弗洛勒斯一所老旧的房子,那是他出生的地方——并且在2011年75岁时向教皇提交了辞职书。他在2010年说:“我开始考虑不得不放下一切选择,每个人都想见证最终的辉煌……但是死亡在我脑海中挥之不去。”为了证明他并不消沉,他依然和信徒们在一起拍照。但是他的面目隐藏不了真相,一位教区居民曾经对他说:“豪尔赫教士,如果你不换张脸,这张照片就没法看了。”

然后,2月11日,本笃十六世没有任何征兆地宣布放弃教皇的职位,这是600年来第一个辞职的教皇。布宜诺斯艾利斯大主教再一次飞往罗马,本以为自己不会是教皇职位的热门人选。但是3月13日,出乎整个世界意料之外,贝尔高利奥以方济各的身份出现在圣彼得大教堂的洋台上。

阿根廷人在他的脸上看到了其它人所无法感知的迹象:悲伤、憔悴的表情一去不返,喜悦就像划破夜空的彗星。

教皇方济各在圣彼得广场接见群众。

万圣节,一名朝圣客在罗马公墓参加弥撒。

在梵蒂冈保安的护卫下,教皇方济各在圣彼得广场亲吻一个婴儿。

祈祷钟声为教皇方济各敲响时,群众挥舞手中的小旗。

一名瑞士保安的身后,教皇向圣彼得广场的人群致意。

梵蒂冈内部,一名瑞士保安在站岗。

教皇在梵蒂冈准备会见哥斯达黎加总统。

在与意大利共和国总统参观奎里纳尔宫时,红衣主教亚斯科(中)与其他梵蒂冈官员在等待。

与意大利总统见面之后,教皇方济各准备回到梵蒂冈。

教皇在一次弥撒中向人群致意,标志着信德年的结束。

在接见“意大利运送病患至露德及国际朝圣地国家联合会”以纪念这个组织成立110周年时,孩子们向教皇方济各致意。

教皇在圣彼得教堂大厅里领导弥撒人群。

改革的限制

方济各教皇职位所给出的承诺和局限性可以用一个7个字的问句来概括:“我有何资格论断?”这是7月份一位记者提出有关同性恋的问题时,他给出的回答。很多人以为,方济各用这样的语言来改变教义,但其实他只是改变了回答问题的腔调,尝试用更务实的方法来接近信众,信徒们已经对教堂的说教极为厌烦。与教区牧师共事多年让他了解到,教堂似乎更愿意面对限制性问题,而不是人类的复杂性问题,在讨价还价的过程中,教民和教堂的可信度都在流失。他敦促团队站在更长远的角度考虑问题。就像他对斯帕达罗所说:“告解神父究竟应该做什么?我们不能紧紧抓住堕胎、同性恋婚姻和避孕问题不放,这不是解决问题的方法。我不大经常接触这类话题,人们因此对我不满。但如果我们要讨论这些问题,我们必须要了解具体事情的背景。”

简言之,就是要用轻松的态度对待热点问题。在美国和其他发达国家这似乎并不算是伟大的进步,但教皇对性取向的敏感度在很多发展中国家造成了一些影响。对同性恋的憎恶已经形成了制度,被广泛的人群所认可。同样,方济各也意识到,富裕的西方国家中出现了给女性授予圣职的自由主义抗议声。他同时知道,在目前的天主教教义中,无法确立女性牧师的合法地位。他曾经说:“在做出重大的决定时,我们总是需要优秀的女性参与。”但这并不包括授予女性圣职。在近期的一次讲话中,他说他希望减少全部由男性担任牧师的数量。不能说因为他们垄断了圣礼,就可以证明他们是唯一得到教堂授权的性别。

在现实的法律框架下,期盼得到平等保护和权力的女性恐怕不会有任何收获。但这些新迹象真正的效果,更可能出现在女性对权力的争取不仅仅局限在得到圣职的国家。在天主教发展最迅速的国家,方济各的话预示了文化战争的伟大进展,女性和其它弱势群体不会永远是输家。亚的斯亚贝巴大主教贝汉内耶苏斯•索拉菲尔谈到女性与教堂的关系时,想到了撒哈拉以南非洲地区的危机,那里普遍存在女性割礼的现象。他试图联合天主教会筹集资金,成立高校,让女性接触更多的教育。索拉菲尔认为方济各有关女性的讲话体现了重要的变革,“这会有很大帮助,因为他说女性在教会和社会中都扮演了重要的角色。”

但是,如果说同性恋和女性地位的问题还多少有些松动的余地,那么对堕胎问题的回答则是毫无悬念的。方济各说:“没有所谓的改革或者‘现代化’进程,为夺走一个人的生命寻找理由无论如何不是一种‘进步’。”尽管如此,方济各在阐述这个问题上时的语调让一些教内保守人士——尤其是在美国——有些坐立不安。有一些主教从前拒绝为赞同堕胎政策的政客提供圣餐服务。这些人的数量不得而知,但没人否认他们的存在。圣母玛利亚大学的神学教授布莱恩•戴利说:“已经出现了一些来自传统组织、保守派的反击,人们觉得他的步子迈得太快了,脱离了本笃的礼拜和牧师任命方式。但这毕竟只是一小部分人。”

几十年来对堕胎和同性恋深恶痛绝的人惊恐地发现,支持他们理论的根基已经在动摇。一些对方济各最尖锐的传统批评人士警告,教皇的角色已经变成了一个普通的主教——当然教皇还在罗马——而不是罗马教宗。他们认为,这样的趋势将终结数百年来世界对教皇的印象。10月初,在玛利亚电台工作的保守派伦理学家马里奥•帕马洛与他人合写了一篇文章《我们不喜欢这个教皇》,其中暗示方济各其实是反基督的人,因为他利用各类媒体来宣扬他的异端邪说。尤其让帕马洛愤怒的是,方济各接受《意大利共和报》无神论编辑的采访,说:“我相信上帝,但不是天主教的上帝。”因为抨击上级领导,帕马洛被电台开除。但是在11月,帕马洛卧病在床时,方济各打电话安慰他。帕马洛对记者说:“接到电话让我很感动,哽咽得无法继续说话。他就是想告诉我,他在为我祈祷。”帕马洛说他没有改变对方济各政策的看法。

保守派批评的部分内容是,方济各的语言和表态无法与前任教皇所遗留下来的内容保持一致。方济各明显意识到这种潜在的争议,他有策略地引用前任罗马教皇的著作,强调一致性。作为第二次梵蒂冈大公会议之后以牧师身份当选的第一位教皇,他对召开改革者大会的约翰二十三世的观点极为慷慨。但这对方济各来说是个微妙的任务,因为他有一个自15世纪以来所有教皇都没有的东西:一个依然健在的前任教皇。尽管本笃已经在梵蒂冈的花园中享受恬静的生活,但他依然保持着巨大的号召力,尤其是对那些担心方济各对教义的把控过于松弛的人来说。到目前为止,方济各和本笃表面上相处融洽,两个人互相恭维,方济各在近期的演说中大量引用本笃的话。方济各无论如何要确保前任教皇站在他这边,因为是本笃把很多天主教信徒心目中的英雄约翰•保罗二世的保守派观点汇编成册。

方济各延续了约翰•保罗二世和本笃的政策,与犹太教保持兄弟间的亲密关系(方济各计划在5月出访耶路撒冷)。但是鉴于他与阿根廷穆斯林移民共事过的经历,方济各或许会比本笃对伊斯兰教采取更温柔的态度。本笃曾经在一次无关紧要的讲话中,对伊斯兰教的神职人员大发脾气。在布宜诺斯艾利斯大教堂,他曾经下跪接受五旬节牧师的祝福,以此证明自己对新教徒、福音教派和愤怒的保守派天主教徒持包容的态度。

当他还在阿根廷时,这位未来的教皇就说,僧侣的独居生活是新生事物(可以追溯到公元1000年),目前似乎面临改变。他还曾经让保守人士大为吃惊地出席了一位反叛主教的葬礼,这位主教离开教堂,与一个寡妇结婚,这个女人曾经和他的丈夫共同出席弥撒。方济各对婚姻不幸的人群报有同情心,他唯一健在的妹妹玛丽亚•艾莉纳•贝尔高利奥就曾经离婚。在阿根廷,他与离婚和再婚的天主教徒关系密切,有些人依然还在参加礼拜活动。教皇在2014年10月召开了一个规模庞大的主教大会,这种规模的会议是50年来的第三次。主要讨论在现代化家庭、性伦理、离婚、同居和生育条件下,牧师所面临的挑战。

一个以世纪为计时单位的场所不大容易发生变化。我们需要知道的是,方济各担任教皇还不到一年时间,一个教皇的态度完全可能发生变化。1846年,教皇庇护九世登基,雄心勃勃地解放天主教会。但到他任期结束时,他变成了保守主义最大的拥护者——就像新成立的意大利国家一样与世俗世界的权力激烈对抗。教堂内部根深蒂固的环境会改变改革者。

生活中的一天

方济各的一天从开始到结束,穿插着无数次祷告。他早上5点起床,祷告到7点,然后在卡萨圣玛尔塔小教堂做早弥撒。之后再次祷告到吃早饭。8点,一天的工作开始。他批阅文件到10点,与部长、红衣主教、主教、牧师和普通信徒会面,直到中午。午餐后是半个小时的午睡时间。接下来是连续6个小时的工作,然后是晚餐和祷告。他承认有时在祷告中会打盹,但他说:“在上帝的注视下入睡是件好事。”他通常晚上10点就寝。

每星期三的午餐时间,他会在圣彼得广场举办教宗接见,通常会有大量群众到场。12月阳光灿烂的一天,有3万人参加接见。这是辉煌的季节,方济各在讲述耶稣复活。他似乎有点感冒,袍子里掖着手帕。但他的声音依然有力,有时高亢,有时低沉,就像一个讲故事的人要模仿故事里不同人物的声音来吸引听众。他手持一份讲稿,每念一段,就有几位牧师用法语、德语、西班牙语、葡萄牙语、英语和阿拉伯语重复一遍。

但他往往无法忍受这样刻板的布道。他放下讲稿,身体前倾,看着群众开始讲话。他的手在空中挥舞,声音愈发有力。他说,耶稣再世!有一天我们也将经历轮回!似乎听众还没有领会他的意思,他继续说:“这不是一个谎言!这是事实!”“你们相信耶稣依然在世吗?”人群回应道:“相信!”他又问:“你们相信吗?”人群回应:“相信!”现在他放心了,人群已经完全领会了他的意思。他谈到基督的爱,就像一个人发现了一个完美的事物,迫不及待地要和别人分享。方济各说:“他在等着我们。”布道即将结束的时候,他再次放下了讲稿:“我们满怀希望!我们正在前往轮回的道路上。这就是我们的喜悦,有一天我们会找到耶稣,一起见到耶稣,所有人一起——不是在这个广场上,而是另外一个地方——与耶稣共享欢愉。这就是我们的宿命。”

布道结束之后,他向讲台上出席的红衣主教致意。然后走下讲台与群众会面,首先与病人见面,然后是特别嘉宾。很多人带给他礼物和纪念品:祭坛上的耶稣圣诞小雕像、基督画像、来自奥地利的装饰画册。一个人与他并肩站在一起拍照,其他人不愿放开他的手。引导员和保安试图让他继续前进,但他还有更多的话要说,更多的人要会见,更多的任务要启动,在这一天过去之前。

我们很难想象遥远的帕萨赫C区究竟是什么样子,但既然方济各可以走到罗马来,那里或许也并不遥远。

原文:

He took the name of a humble saint and then called for a church of healing. The first non-European pope in 1,200 years is poised to transform a place that measures change by the century

On the edge of Buenos Aires is a nothing little street called Pasaje C, a shot of dried mud leading into a slum from what passes for a main road, the garbage-strewn Mariano Acosta. There is a church, the Immaculate Virgin, toward the end of the pasaje—Spanish for passage—where, on one occasion, the local priest and a number of frightened residents took refuge deep in the sanctuary when rival drug gangs opened fire. Beyond the church, Pasaje C branches into the rest of the parish: more rutted mud and cracked concrete form Pasajes A to K. Brick chips from the hasty construction of squatter housing coagulate along what ought to be sidewalks. The word asesino— murderer—is scrawled in spray-paint on the sooty wall of a burned-out house, which was torched just days before in retaliation for yet another shooting. Packs of dogs sprawl beneath wrecked cars. Children wander heedless of traffic, because nothing can gather speed on these jagged roads. But even Pasaje C can lead to Rome.

As Cardinal and Archbishop of Buenos Aires, a metropolis of some 13.5 million souls, Jorge Mario Bergoglio made room in his schedule every year for a pastoral visit to this place of squalor and sorrow. He would walk to the subway station nearest to the Metropolitan Cathedral, whose pillars and dome fit easily into the center of Argentine power. Traveling alone, he would transfer onto a graffiti-blasted tram to Mariano Acosta, reaching where the subways do not go. He finished the journey on foot, moving heavily in his bulky black orthopedic shoes along Pasaje C. On other days, there were other journeys to barrios throughout the city—so many in need of so much, but none too poor or too filthy for a visit from this itinerant prince of the church. Reza por mí, he asked almost everyone he met. Pray for me.

When, on March 13, Bergoglio inherited the throne of St. Peter—keeper of the keys to the kingdom of heaven—he made the same request of the world. Pray for me. His letter of retirement, a requirement of all bishops 75 and older, was already on file in a Vatican office, awaiting approval. Friends in Argentina had perceived him to be slowing down, like a spent force. In an instant, he was a new man, calling himself Francis after the humble saint from Assisi. As Pope, he was suddenly the sovereign of Vatican City and head of an institution so sprawling—with about enough followers to populate China—so steeped in order, so snarled by bureaucracy, so vast in its charity, so weighted by its scandals, so polarizing to those who study its teachings, so mysterious to those who don’t, that the gap between him and the daily miseries of the world’s poor might finally have seemed unbridgeable. Until the 266th Supreme Pontiff walked off in those clunky shoes to pay his hotel bill.

The papacy is mysterious and magical: it turns a septuagenarian into a superstar while revealing almost nothing about the man himself. And it raises hopes in every corner of the world—hopes that can never be fulfilled, for they are irreconcilable. The elderly traditionalist who pines for the old Latin Mass and the devout young woman who wishes she could be a priest both have hopes. The ambitious monsignor in the Vatican Curia and the evangelizing deacon in a remote Filipino village both have hopes. No Pope can make them all happy at once.

But what makes this Pope so important is the speed with which he has captured the imaginations of millions who had given up on hoping for the church at all. People weary of the endless parsing of sexual ethics, the buck-passing infighting over lines of authority when all the while (to borrow from Milton), “the hungry Sheep look up, and are not fed.” In a matter of months, Francis has elevated the healing mission of the church—the church as servant and comforter of hurting people in an often harsh world—above the doctrinal police work so important to his recent predecessors. John Paul II and Benedict XVI were professors of theology. Francis is a former janitor, nightclub bouncer, chemical technician and literature teacher.

And behind his self-effacing facade, he is a very canny operator. He makes masterly use of 21st century tools to perform his 1st century office. He is photographed washing the feet of female convicts, posing for selfies with young visitors to the Vatican, embracing a man with a deformed face. He is quoted saying of women who consider abortion because of poverty or rape, “Who can remain unmoved before such painful situations?” Of gay people: “If a homosexual person is of good will and is in search of God, I am no one to judge.” To divorced and remarried Catholics who are, by rule, forbidden from taking Communion, he says that this crucial rite “is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

Through these conscious and skillful evocations of moments in the ministry of Jesus, as recounted in the Gospels, this new Pope may have found a way out of the 20th century culture wars, which have left the church moribund in much of Western Europe and on the defensive from Dublin to Los Angeles. But the paradox of the papacy is that each new man’s success is burdened by the astonishing successes of Popes past. The weight of history, of doctrines and dogmas woven intricately century by century, genius by genius, is both the source and the limitation of papal power. It radiates from every statue, crypt and hand-painted vellum text in Rome—and in churches, libraries, hospitals, universities and museums around the globe. A Pope sets his own course only if he can conform it to paths already chosen.

And so Francis signals great change while giving the same answers to the uncomfortable questions. On the question of female priests: “We need to work harder to develop a profound theology of the woman.” Which means: no. No to abortion, because an individual life begins at conception. No to gay marriage, because the male-female bond is established by God. “The teaching of the church … is clear,” he has said, “and I am a son of the church, but”—and here he adds his prayer for himself—“it is not necessary to talk about those issues all the time.”

If that prayer should be answered, if somehow by his own vivid example Francis could bring the church into a new relationship with its critics and dissidents—agreeing to disagree about issues that divide them while cooperating in the urgent mission of spreading mercy—he might unleash untold good. “Argue less, accomplish more” could be a healing motto for our times. We have a glut of problems to tackle. Francis says by example, Stop bickering and roll up your sleeves. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good—an important thing for the world to hear, especially from a man who holds an office deemed infallible.

Thousands turn out in Rome to greet Francis during his biweekly audiences.

A Changing Papacy

This papacy begins with a name. Jorge Bergoglio is the first Pope to choose as his namesake Francis of Assisi, the 13th century patron saint of the poor. The choice, coming after 14 Clements, 16 Benedicts and 21 Johns, is clearly and pointedly personal. The 13th century Francis turned to the ministry when, as legend has it, he heard a voice calling to him from a crucifix to repair God’s house. He left his prosperous silk-merchant family to live with the poor. He was a peacemaker, the first Catholic leader to travel to Egypt to try to end the Crusades. He placed mercy at the core of his life.

From that name follows much of Francis’ agenda. While the Catholic Church envisioned by Benedict XVI was one of tightly calibrated spiritual prescriptions, Francis told Father Antonio Spadaro, editor of the Jesuit magazine Civiltà Cattolica, in an interview published at the end of September, that he sees “the church as a field hospital after battle.” His vision is of a pastoral—not a doctrinaire—church, and that will shift the Holy See’s energies away from demanding long-distance homage and toward ministry to and embrace of the poor, the spiritually broken and the lonely. He expanded on this idea in a 288-section apostolic exhortation called “Evangelii Gaudium,” or “The Joy of the Gospel.” “I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security,” he wrote. He made it clear that he does not just want talk—he wants actual transformation.

He has halted the habit of granting priests the honorific title of monsignor as a way to stem careerism in the ranks and put the focus instead on pastoring. He told a gathering of his diplomats that he wanted them to identify candidates for bishop in their home countries who are, he said, “gentle, patient and merciful, animated by inner poverty, the freedom of the Lord and also by outward simplicity and austerity of life.” To Francis, poverty isn’t simply about charity; it’s also about justice. The church, by extension, should not reflect Rome; it should mirror the poor.

Which helps explain why he has turned the once obscure Vatican Almoner, an agency that has been around for about 800 years and is often reserved for an aging Catholic diplomat, over to the dynamic 50-year-old Polish Archbishop Konrad Krajewski and told him to make it the Holy See’s new front porch. “You can sell your desk,” Francis told Krajewski. “You don’t need it. You need to get out of the Vatican. Don’t wait for people to come ringing. You need to go out and look for the poor.” The Archbishop hands out small amounts to the needy, including a recent gift of 1,600 phone cards to immigrant survivors of a capsized boat so they could call family back in Eritrea. Francis often gives Krajewski stacks of letters with his instructions to help the people who have written to him and asked for aid. In what sounds like a necessary precaution, the Vatican recently issued a denial after Krajewski hinted that Francis himself sometimes slips out of the Vatican dressed as an ordinary priest to hand out alms.

Francis also moved early to tame the mess that is the Vatican Bank, an institution even U.S. Treasury officials privately say is corrupted. Soon after he was elected, he named a special commission to investigate the bank, which in turn handed the matter off to an independent firm for an audit. Francis also issued initiatives to counter money laundering and increase the monitoring of the Vatican’s finances. In October, the bank disclosed an annual report for the first time in its 125-year history.

And if personnel is policy, Francis has been particularly busy, shaking up the Curia with his preference for new faces over old ones. In a move that signifies he means business, he tossed Benedict’s Secretary of State, Tarcisio Bertone, and named ambassador to Venezuela Archbishop Pietro Parolin, the youngest man to hold the post since Eugenio Pacelli, who went on to become Pope Pius XII in 1939.

In April, Francis tapped a boarding party of eight like-minded bishops from around the world to meet with him several times a year to comb through difficult problems, a move that diffused some of the traditional power of the Synod of Bishops. “I don’t want token consultations,” he explained in an interview, “but real consultations.” That, at least so far, appears to be what he is getting. The membership is telling: Cardinals from Chile, Congo and Honduras as well as Munich, Australia and Boston are on the panel. In August, another member, Cardinal Oswald Gracias of India, issued one of the most expansive comments about gays that the church has ever made, stating that while the church does not allow gay marriage, homosexuality is not a sin. “To say that those with other sexual orientations are sinners is wrong,” he wrote to an LGBT group in Mumbai. “We must be sensitive in our homilies and how we speak in public and I will so advise our priests.”

And on Dec. 5, in a long overdue move, the group of eight named a new commission on sex abuse, the problem of priests preying on children they had vowed to protect. It is the church’s darkest existential problem in an era of existential problems; the commission aims to study better ways to protect children, screen programs that involve children and suggest new ways to create safe environments and choose the priests to lead them. At worst, the Cardinals are laying out a new set of best practices for far-flung dioceses to follow. At best, they are admitting that the Vatican had focused too much attention on the legal challenges of the sex-abuse crisis rather than on the behavioral problems at its core.

Francis has backed up his deeds with homilies and his first apostolic exhortation. He can barely contain his outrage when he writes, “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?” Elsewhere in his exhortation, he goes directly after capitalism and globalization: “Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion … has never been confirmed by the facts.” He says the church must work “to eliminate the structural causes of poverty” and adds that while “the Pope loves everyone, rich and poor alike … he is obliged in the name of Christ to remind all that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor.”

The church has always made the poor a priority— a mission that has been the biting paradox of the treasure-laden Vatican. But Francis has made it clear that they are a priest’s first responsibility. “A lack of vigilance, as we know, makes the Pastor tepid; it makes him absentminded, forgetful and even impatient,” he preached in May. “It tantalizes him with the prospect of a career, the enticement of money and with compromises with a mundane spirit; it makes him lazy, turning him into an official, a state functionary, concerned with himself, with organization and structures, rather than with the true good of the People of God.” In case anyone missed the point, he suspended a bishop in Limburg, Germany, for overseeing a $42.5 million renovation of the church residence that included a $20,500 bathtub. Says Father Guillermo Marcó, who was Bergoglio’s spokesman from 1998 to 2006: “It is the first time we have had a priest as Pope.”

An Argentine’s Way

On weekends in Buenos Aires, you can take a 31⁄2-hour bus tour of the neighborhoods where Jorge Mario Bergoglio grew up. “What’s coming up on this street?” the tour guide Daniel Vega asks as the bus pulls up on Calle Membrillar in the Flores district of Buenos Aires. “The house where he was born,” comes the answer. There’s the chapel where his father Mario, a native of the Piedmont region of Italy, and Regina, an Argentine of Piedmontese descent, met in 1934. They married the next year and had their firstborn, Jorge Mario, on Dec. 17, 1936.

The Bergoglios were very strict Catholics, the kind who worry about meeting people who were not married in the church or who were socialists or atheists. But the future Pope was never that doctrinaire: in the four years between realizing he was called to the priesthood and actually entering seminary, he said he had “political concerns, though I never went beyond simple intellectualizing.” He admits to reading and liking publications of the Communist Party but says he was never a member. Many Bergoglio watchers—a minor industry in Argentina—believe that his concern for the destitute is partly rooted in Argentina’s experience with Peronism, a strange socialist-capitalist amalgam that evolved in the country in the 1940s and was powered by a deep, working-class populism. That ideology suffused everything Argentine then—and now.

Bergoglio is quite mystical about his career choice, which hit him when he stopped off at church on his way to join friends to celebrate a holiday. “It surprised me, caught me with my guard down,” he told Francesca Ambrogetti and Sergio Rubin, who interviewed him for their 2010 book, published this year in the U.S. as Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio. “That is the religious experience: the astonishment of meeting someone who has been waiting for you all along.” He did not enter seminary until 1957, telling the authors, “Let’s say God left the door open for me for a few years.”

He was briefly a nightclub bouncer and would as a 21-year-old seminarian lose most of his right lung to an infection, a condition that may contribute to his back problems today. He chose to join the Jesuits because the order—founded as the Catholic Church launched th e counterreformation—was at “the front lines of the Church, grounded in obedience and discipline.” He claimed to not be disciplined himself and thus in need of the structure. What he did have was a talent for empathy and for engaging people in conversation. Even before he was ordained, he was a popular and attractive figure to his students at Jesuit schools as well as to many superiors. In 1973, at 36—just three years a priest—he was named the head of the Society of Jesus in Argentina and the boss of Jesuits many years his senior. The office came with prestige, huge responsibilities and, as it turned out, the seeds of almost two decades of turmoil for himself, which nearly derailed his career.

His crisis centered around two Jesuits, Father Orlando Yorio and Father Francisco Jalics, who refused his orders over the period of about a year beginning in 1975 to leave the slums as the country spiraled into political chaos and the military, which considered slum priests to be likely rebels, was clearly moving to take over Argentina. As terrorists on the right and left tore the nation apart, many Argentines— including some bishops and priests—longed for a strong hand to reassert control over the country, and many welcomed the military coup of March 24, 1976.

In May the two Jesuits were arrested and subjected to torture. Bitterness has lingered among some Jesuits and the relatives of Yorio (who died in 2000), who to this day accuse Bergoglio of virtually giving up the priests to the junta, citing a flurry of bureaucratic paperwork that ultimately failed to provide cover for the clerics to stay on in the slums. Bergoglio said he immediately tried to win their freedom (as he would do for many others), and Yorio and Jalics were released after five months. Very few of the “disappeared”—as abducted Argentines were called—reappeared alive.

Even after Bergoglio served out his term as Jesuit provincial in 1979, he remained a divisive figure. In 1988, when he was serving as a theology lecturer at a school in Buenos Aires, he came into conflict with the provincial at the time, Father Victor Zorzín, who reassigned Bergoglio to Córdoba, more than 400 miles (640 km) northwest of Buenos Aires. From June 1990 to May 1992, according to journalist Elisabetta Piqué, author of the biography Francis: Life and Revolution, he could make no phone calls without permission, and his correspondence was “controlled.” Zorzín says “it cost [Bergoglio] a lot to accept the change. But pain can ripen into something else.”

In what would prove to be a providential turn, a Cardinal who admired Bergoglio’s work as provincial— including his ability to assess the talents of others and organize productive meetings—came seeking him and, rescuing him from Córdoba exile, turbocharged his ascent in the church hierarchy. And as he rose from bishop to Archbishop to Cardinal, Bergoglio began ministering to the slums—the same kind of districts that Yorio and Jalics refused to leave at his orders. Jalics, who now lives in Bavaria, kept silent about the case for nearly four decades but released a statement after Bergoglio became Francis, declaring that “Orlando Yorio and I were never given up by Jorge Bergoglio … I used to think we had been victims of an accusation. But by the late 90s, after many conversations, it was clear to me that I was wrong.”

After becoming Archbishop in 1998, Bergoglio was known for his frugality, for taking the bus and the subway and for living in a simple apartment on the same block as the cathedral, not at the opulent archdiocesan residence. That kind of humility increased his appeal not only with ordinary Argentines but also among his fellow Archbishops in Latin America. His meteoric postexile rise seemed to climax in April 2005, when the death of John Paul II brought Bergoglio to Rome and to the ranks of what Vaticanologists call I papabili—the Cardinals who might become Pope. The Wednesday after Germany’s Joseph Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI, Bergoglio had lunch with his press secretary Marcó and, according to Marcó, never let on that the Latin American Cardinals had gathered enough support to make him the runner-up in the conclave. Some accounts have Bergoglio signaling to his supporters to shift their votes to Ratzinger so as not to prolong the process and give an impression of a divided College of Cardinals.

He returned to Buenos Aires and looked to retirement. He had already picked out the residence where he would live out the rest of his life—an old-age home for priests in Flores, where he was born—and handed his letter of resignation to the Pope when he turned 75 in 2011. “I’m starting to consider the fact that I have to leave everything behind,” he said in 2010. “It makes me want to be fair with everyone always, to sign the final flourish … But death is in my thoughts every day.” He insisted he was not sad, and he went on posing for pictures with the faithful. But his face gave him away, and one parishioner called him on it: “Padre Jorge, if you’re going to put on that face, you’re going to ruin the photo.”

Then without warning on Feb. 11, Benedict XVI announced that he was abdicating the papacy, the first time a Pope had resigned in 600 years. The Archbishop of Buenos Aires once again flew to Rome, though he was no longer on the hot list of I papabili. But on the night of March 13, to the world’s surprise, Bergoglio emerged on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica as Francis.

Argentines saw on his face what millions of others could not have divined: the sad, haggard look was gone. Joy cometh in the evening.

Francis has made society’s most vulnerable—the sick, the elderly, immigrants and children—the focus of his ministry.

The Limits Of Reform

The five words that have come to define both the promise and the limits of Francis’ papacy came in the form of a question: “Who am I to judge?” That was his answer when asked about homo sexuality by a reporter in July. Many assumed Francis, with those words, was changing church doctrine. Instead, he was merely changing its tone, searching for a pragmatic path to reach the faithful who had been repelled by their church or its emphasis on strict dos and don’ts. Years of working closely with parish priests have taught him that the church seemed more comfortable with narrow issues than human complexity, and it lost congregants and credibility in the bargain. He is urging his army to think more broadly. As he told Spadaro, “What is the confessor to do? We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods. That is not possible. I have not spoken much about these things and I was reprimanded for that. But when we speak about these issues, we have to talk about them in a context.”

In short, ease up on the hot-button issues. That might not seem like significant progress in the U.S. and other developed nations. But the Pope’s sensitivity to sexual orientation has a different impact in many developing countries, where homo phobia is institutionalized, widespread and sanctioned. Similarly, Francis is aware of the liberal clamor in the affluent West for the ordination of women. He also recognizes that Catholic doctrine, as it is currently formulated, cannot be made to justify women as priests. “The feminine genius is needed wherever we make important decisions,” he has said. But that does not involve ordination as priests. Instead, in his recent exhortation, he says he wants to diminish the primacy of the all-male priesthood, arguing that just because they monopolize the sacraments does not mean their gender should be the only one empowered in the church.

That won’t make the grade for women who expect equal protection and rights under secular law. But the real significance of these new horizons will likely come in countries where the stakes for women are far higher than just the question of ordination. In the places where the Catholic Church is growing fastest, Francis’ words may portend significant advances in culture wars where women and other disadvantaged groups have always been on the losing side. When Catholic Archbishop Berhaneyesus Souraphiel of Addis Ababa talks of women in the church, he thinks of the crisis in sub-Saharan African regions where female genital mutilation is common. He is trying to rally Catholics to raise money to build a university where women can have greater access to education. Souraphiel sees great progress in Francis’ statements about women. “It could help a lot,” he says, “because he is saying women have a great role in the church and in society.”

But if there appears to be some wiggle room on homosexuality and the role of women, there is none for abortion. “This is not something subject to alleged reforms or ‘modernizations,’” Francis says. “It is not ‘progressive’ to try to resolve problems by eliminating a human life.” Even so, Francis’ tonal shifts on doctrine have unsettled some church conservatives, particularly in the U.S., where some bishops in the past have declined to offer Communion to elected officials who favor abortion. The exact size of this group is unknown, but no one denies it exists. “Already there has been a lot of backlash from traditionalist groups, conservative groups, people who feel he is moving too quickly away from the traditional style of Benedict on liturgy, on clerical appointments,” says Brian Daley, a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame. “But that’s probably a relatively small group of people.”

Those who have inveighed against abortion and homosexuality for decades may fear that the ground is shifting underneath their feet. Some of the harshest criticisms of Francis have come from traditionalists alarmed at his emphasizing the Pope’s role as just another bishop— albeit of Rome—rather than Supreme Pontiff. They argue that this path would lead to the end of the papacy as the world has known it for centuries. In early October, Mario Palmaro, a conservative bioethicist who worked for Radio Maria, went so far as to co-author an essay titled “We Do Not Like This Pope” that hinted that Francis was the Antichrist because of his all-too-knowing use of the media to propagate heterodox ideas. Palmaro was particularly appalled by the interview Francis granted the atheist editor of the Italian daily La Repubblica, in which the Pope was quoted as saying, “I believe in God, not a Catholic God.” The station fired Palmaro for criticizing the boss. But in November, after Palmaro came down with a debilitating disease, Francis telephoned to console him. “I was so moved by the phone call that I was not able to conduct much conversation,” Palmaro told reporters. “He just wanted to tell me that he is praying for me.” Palmaro says he has not changed his opinion of Francis’ policy.

Part of the conservative critique is that Francis’ words and gestures cannot be fully reconciled with the legacy of previous Popes. Apparently aware of that potential for controversy, Francis has been skillfully citing the writings of former Pontiffs, stressing continuity. As the first Pontiff to be ordained a priest after Vatican II, he has been generous to the opinions of John XXIII, who convened that reformist council. But it is a delicate task given that Francis has one thing no Pope has had since the 15th century: a living predecessor. While Benedict resides in quiet retirement in the Vatican Gardens, he remains a potential rallying point for those who fear that Francis may hold the doctrinal reins too loosely. So far, Francis and Benedict appear to get on well: both men flatter each other, and Francis was especially generous with quotations from Benedict in his recent exhortation. In any case, Francis needs to keep his predecessor on his side, for it was Benedict who codified the conservative views of John Paul II, the hero of many Catholics, particularly those on the right of the spectrum.

Francis will continue the policy of both John Paul II and Benedict on détente and fraternal relations with Judaism. (Francis plans to visit Israel in May.) But with his experience working with the Muslim immigrant population of Argentina, Francis will extend a warmer hand toward Islam than Benedict, who famously infuriated that religion’s clerics with a scholarly aside in an otherwise innocuous speech. And he has proved himself amenable to Protestant, evangelical piety, scandalizing conservative Catholics in Argentina by kneeling and being blessed by Pentecostal preachers in a Buenos Aires auditorium.

While still in his home country, the future Pope also said that priestly celibacy is a recent development (it dates to about the year 1000) and has seemed open to change. Again, in Argentina, he startled conservatives by attending the funeral of a rebel bishop who left the church to marry, comforting the deceased prelate’s widow, who used to concelebrate Mass with her husband. Francis is sympathetic to people whose marriages have fallen apart: his only surviving sibling, María Elena Bergoglio, is divorced. In Argentina, he worked very closely with Catholics who were divorced and remarried, some of whom continue to take Communion. The Pope has called an Extraordinary Synod of Bishops—only the third such gathering in almost 50 years—in October 2014 to discuss pastoral challenges that face modern families, including sexual ethics, divorce, cohabitation and reproduction.

A place that measures change in terms of centuries doesn’t do relaunches often. It is important to remember that Francis has been Pope for less than a year, and a papacy can change character in midstream. In 1846, Pope Pius IX came to the throne as the great hope to liberalize Catholicism but by the end of his pontificate had become the great champion of conservatism—the font of infallibility and angry confrontation with secular powers like the newborn Italian state. The entrenched dynamics of the church can transform the would-be transformer.

A Day In The Life

Francis begins, ends and dots his day with prayer. He rises at 5 a.m. and prays until 7 before celebrating morning Mass at the Casa Santa Marta chapel. He prays after Mass and again before breakfast. Then at 8 a.m., the day begins. He works through papers until 10, then meets with secretaries, Cardinals, bishops, priests and laypeople until noon, followed by lunch and a half-hour siesta. Six hours of work follow, then dinner and more prayer in front of the Blessed Sacrament. He admits he sometimes nods off at this point, but says, “It is good to fall asleep in God’s presence.” He is usually in bed by 10.

On Wednesdays, he has a general audience around lunchtime in St. Peter’s Square, which brings in the multitudes. On a bright December day, the festive crowd numbers about 30,000. It’s the season of light, and Francis is talking about the Resurrection. He appears to have a cold; he needs the handkerchief tucked in his robes. But his voice is strong, though higher than you’d expect, and more musical, like that of a storyteller with a full range of context and characters to bring to his mission of making you listen. He has a script in hand because once he finishes the lesson, it will be repeated by priests reading in French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, English and Arabic.

Francis hopes to bring the gospel of mercy to the church—and the world.

But every so often, he can’t help himself. The script falls to his lap and he leans forward, looks out over the crowd and just starts talking, his hands in the air, his voice stronger now, doing his own call and response. Jesus is risen, and so shall we be one day, he tells them. And as though they might not quite grasp the implication, he pushes them: “But this is not a lie! This is true!” he says. “Do you believe that Jesus is alive? Voi credete?” “Yes!” the crowd calls back, and he asks again, “Don’t you believe?” “Yes,” they cry. And now he has them. They have become part of the message. He talks about Christ’s love like a man who has found something wondrous and wants nothing more than to share it. “He is waiting for us,” Francis says. And when he comes to the end of his homily, the script drops once more. “This thought gives us hope! We are on the way to the Resurrection. And this is our joy: one day find Jesus, meet Jesus and all together, all together—not here in the square, the other way—but joyful with Jesus. This is our destiny.”

Once the service ends, he greets the Cardinals in attendance on the dais, then walks over to meet first with the sick, then with special guests. Many have brought him gifts, mementos: a small statue of a merry Jesus on a yellow silk altar, a painting of Christ, a coffee-table book of photos from Austria. One man poses with him for a selfie; others do not want to let go of his hand. The ushers and security guards try to keep him moving, but he has more words to speak, pilgrims to meet and missions to launch before the day is over.

It’s hard to imagine a setting farther from Pasaje C. But if Francis can order his steps, it’s not so far at all.

|