|

|

【中文标题】一百张最有影响力的照片 之三

【原文标题】Most Influential Photos

【登载媒体】时代周刊

【原文作者】Ben Goldberger

【原文链接】http://100photos.time.com/photos/harold-edgerton-milk-drop

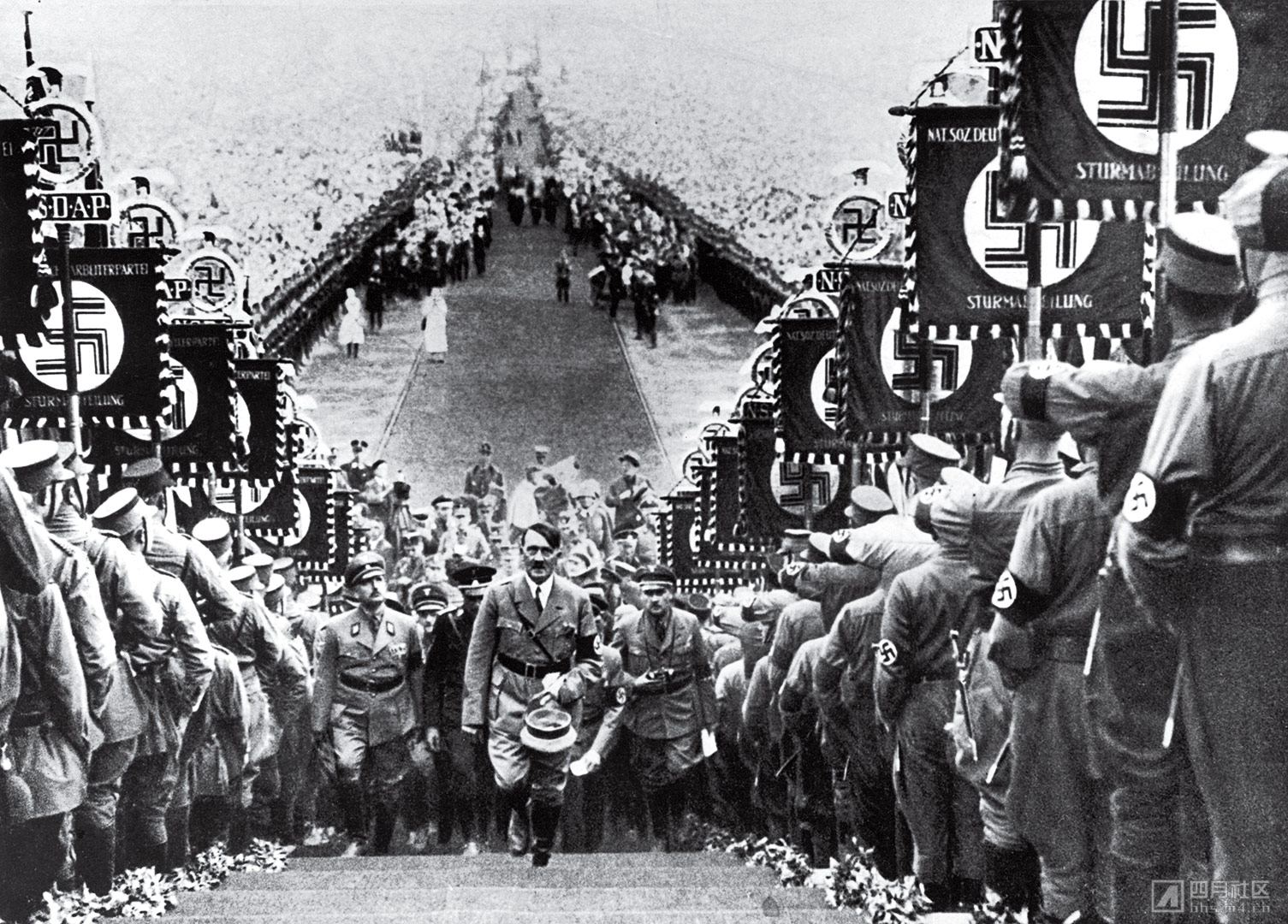

纳粹党集会上的希特勒

海因里希•霍夫曼

1934年

宏大的仪式就像是纳粹的氧气,海因里希•霍夫曼是彰显希特勒盛大权力象征的关键人物。霍夫曼在1920年加入纳粹党,成为了希特勒的私人摄影师和密友,他被要求设计第三帝国的宣传盛况,并强加给受伤的德国民众。他最成功的表现发生在1934年9月30日,在巴克博格丰收节一张左右严格对称的照片上,冷酷的元首大摇大摆地走在瓦格纳风格的崇拜和致敬军队中间。通过这张照片,以及其它很多夸张的造型,霍夫曼——他共拍摄了200万张希特勒的照片——给帝国巨大的宣传机器提供了无限的素材,延伸了它的统治梦想。这些照片在希特勒的第三帝国中无处不在,而帝国巧妙地利用霍夫曼的照片、纳粹旗帜上的标志和雷妮•瑞芬舒丹的纪录片,营造出雅利安人应该得到上帝般崇拜的景象。在遭受了一战失败的羞辱、惩罚性的战争赔款和经济大萧条之后,一个渴望重获尊严的国家被希特勒的表情和他似乎不可置疑的拨乱反正的欲望凝聚在一起。霍夫曼用大师手法呈现出的宣传攻势,证明了摄影改变国家,让世界陷入战争的力量。

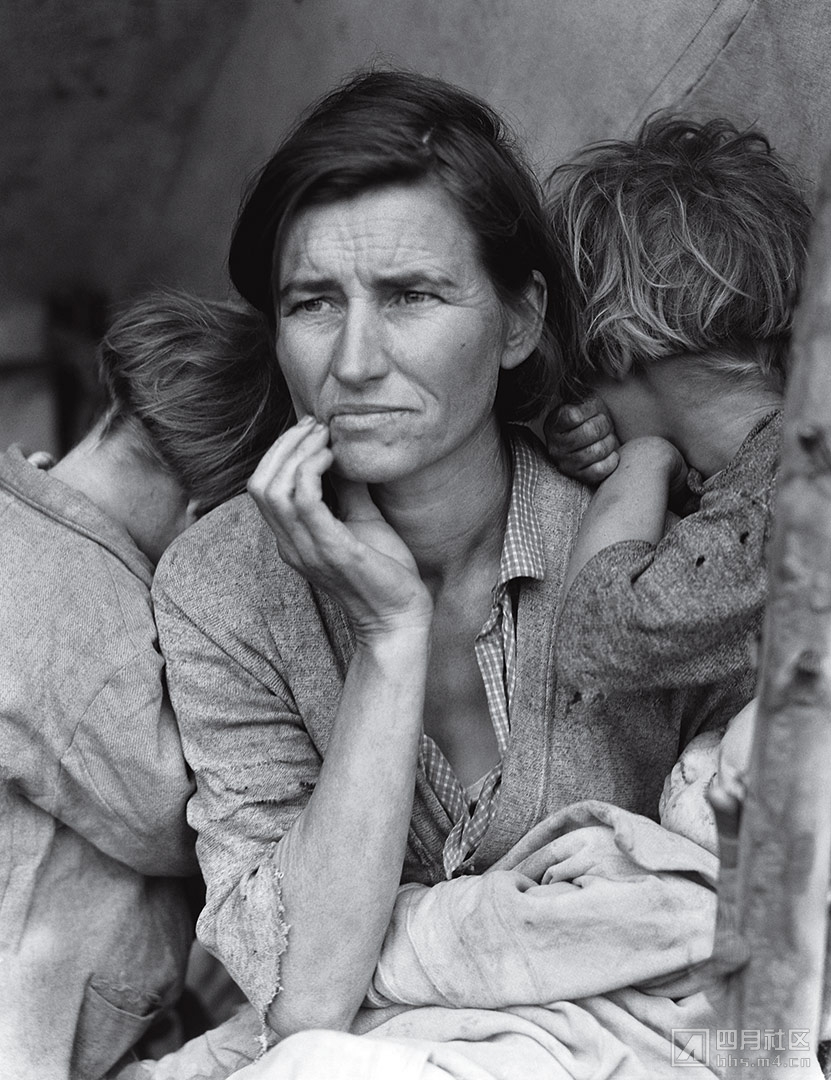

移民母亲

多萝西•兰格

1936年

这张用超越一切的笔触,人性化表现大萧条所造成的代价的照片,差一点就没能出现。多萝西•兰格驾车路过洛杉矶北部尼波莫粗制滥造的“豌豆采摘营”标志牌之后,又开了20英里。但是政府居民再安置办公室的一些信息似乎让这位摄影师想到了什么,于是她调头往回开。在营地里,出生在纽约霍博肯的兰格看见到了弗朗西斯•欧文斯•汤普森,她立即知道自己来对了。兰格在后来写到:“我看到这位饥饿、绝望的母亲坐在临时搭建的破帐篷里,向她走近,就好像被一块磁石吸引。”田里都是冻土,这些无家可归的采摘客没有工作可做,32岁的汤普森只好卖掉车上的轮胎,买一些食物,加上孩子们捉到的几只鸟,权作充饥。兰格相信近距离的观察可以更好地了解对方,于是把相机的取景框对准孩子和母亲。母亲的目光充满焦虑和沮丧,她望着远方。兰格用她的4×5格拉菲相机拍了6张照片,后来写到:“我知道,我的相机已经记录下我这份工作的精华所在。”后来,兰格把营地居民的困苦状告告诉当局,他们送来了2万磅的食物。在兰格和其他摄影师为居民再安置办公室拍摄的16万张照片中,“移民母亲”是大萧条时期标志性的代表。通过对全国各地牺牲品的形象刻画,兰格展示了一个国家痛苦挣扎的面孔。

倒下的士兵

罗伯特•卡帕

1936年

罗伯特•卡帕拍摄这张造成巨大影响的西班牙内战照片时,并没有看取景器。这张照片被广泛认为是历史上最优秀的战争摄影作品之一,第一个在战争行动中被子弹击中的镜头。1947年,卡帕在电台接受采访时说,他当时和共和国民兵躲在战壕里。民兵试图冲上地面,夺取由效忠弗朗西斯科•佛朗哥的军队控制的机枪,但每一次冲锋都被对方的射击压制。一次冲锋时,卡帕把相机举过头顶,按下快门,结果出现了这张士兵中弹倒地的戏剧性动作场面。

到了20世纪70年代,这张照片在法国杂志上发表了几十年之后,一名南非记者O•D•加拉戈尔说,卡帕告诉他这那张照片是摆拍的。但这一点一直没有被确认,大部分人相信卡帕的照片是一名西班牙民兵中弹倒地的真实记录。卡帕的照片把战争摄影提升到一个新的高度,记者们在很久之后才正式进入军队,让人们看到摄影师参与战争是多么的至关重要,又是多么的危险。

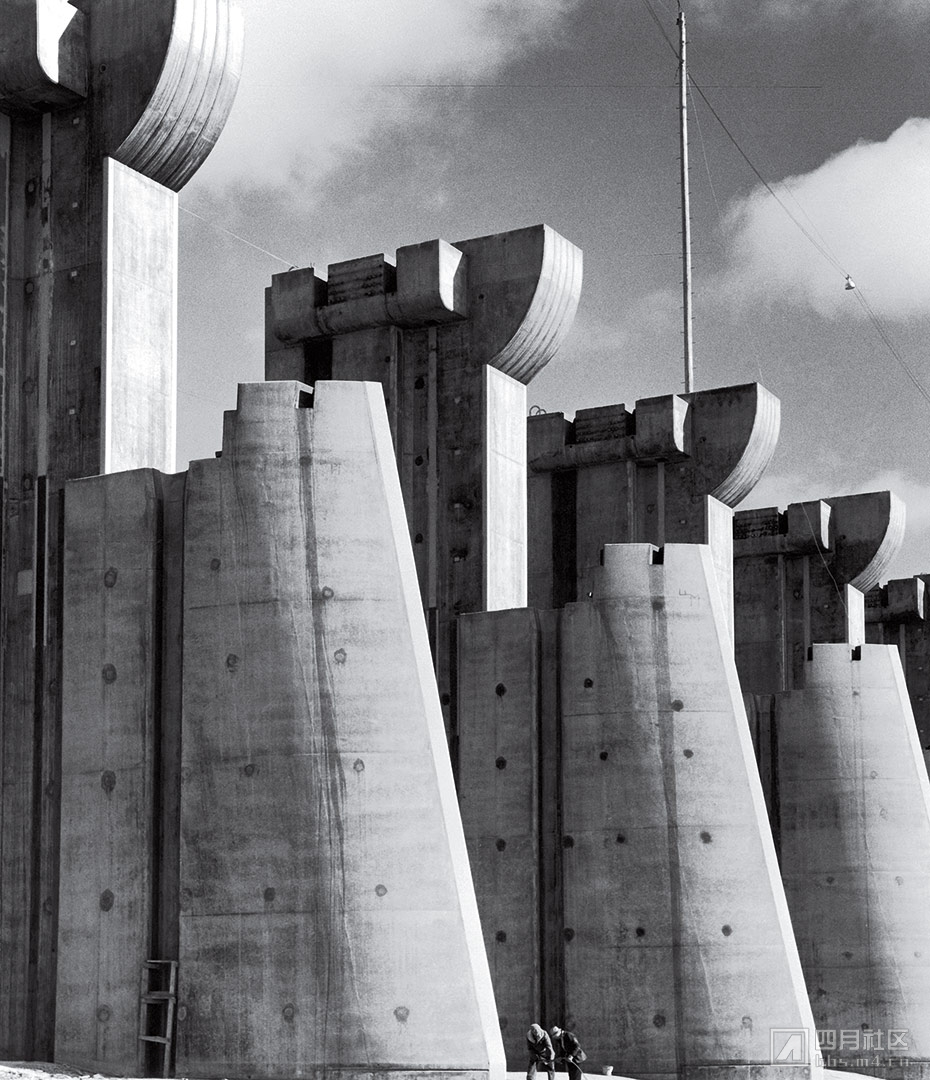

佩克堡大坝

玛格丽特•博克•怀特

1936年

《生活》杂志的目的是迅速成为当时最有影响力的新闻和图片媒体,因此它在1936年11月创刊号上骄傲地宣布,它会用独特的视觉角度讲述具有巨大影响力和复杂内容的新闻故事。还有谁比得上亨利•卢斯的《财富》杂志摄影师玛格丽特•博克•怀特拍摄的《生活》照片故事——修建中的蒙大拿佩克堡大坝照片呢?博克•怀特用城堡一样的建筑结构照片和一篇介绍文章,把世界上最大的泥土大坝赋予了人性的感觉。她关注的焦点不仅仅是罗斯福新政下密苏里河盆地的这项巨大工程所面临的技术挑战,而且提到了狂野西部那种“破旧不堪的城镇”的氛围,一个“充满了建筑工人、工程师、电焊工、江湖医生、酒吧女招待和妓女”的地方。博克•怀特的封面决定了这份杂志的新闻摄影风格,也为《生活》杂志后来出现的那些伟大的摄影师奠定了基调。正如她的同事、杰出的战争摄影记者卡尔•麦单斯所说,博克•怀特的影响力“无法估量”。

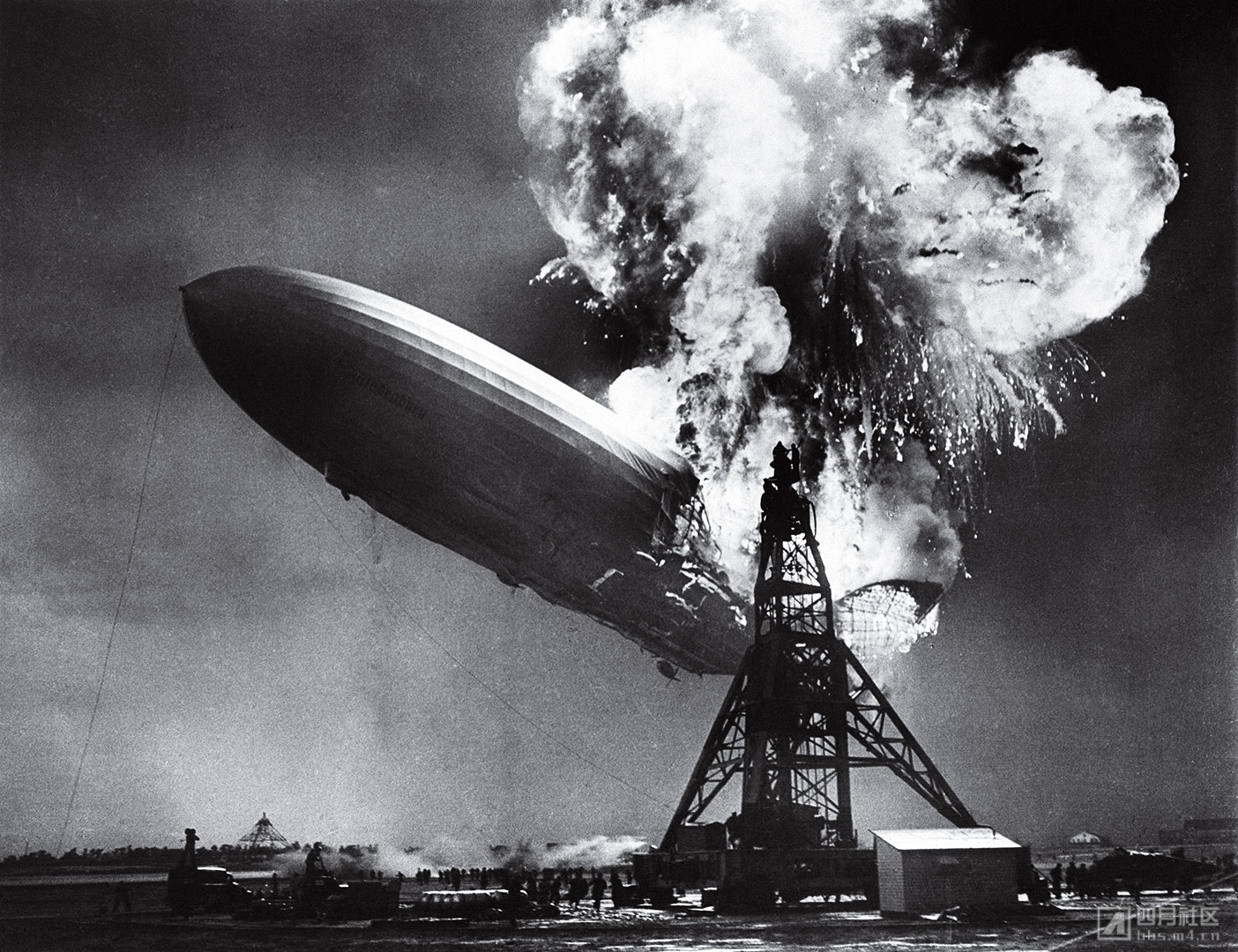

兴登堡空难

山姆•希尔

1937年

齐柏林是雄伟壮观的客运飞行器,这些装饰豪华的庞然大物象征着财富和权力。飞艇到达之处都会引起当地新闻界的关注,这就是为什么国际新闻照片社的山姆•希尔会在1937年5月6日纽约莱克赫斯特海军航空站冒雨等待,804英尺长的LZ129型来自法兰克福的兴登堡号缓缓飘近。突然之间,就在各路媒体的注视下,飞艇的氢气燃料着火,闪出耀眼的黄色火焰,36人丧生。数十名摄影记者匆忙记录下这祸从天降的时刻,希尔是其中之一。他那张具有无比直观性和巨大恐惧感的照片最为著名,因为它出现在全世界所有著名媒体和《生活》杂志的首页。三十多年之后,它还被用作齐柏林飞船乐队第一张专辑的封面。这场灾难为飞艇航空时代画上了句号。希尔具有强大视觉冲击力的照片作为世界上最早的空难现场直击,长久以来警示着人们,人类的错误将会导致死亡和毁灭。几乎与希尔的照片同样铭刻于心的是芝加哥播音员赫伯特•莫里森痛苦的声音。当看到人们从空中跌落时,他失声痛哭:“它着火了……太可怕了。这是世界上最恐怖的灾难……噢,人类啊!”

血腥星期六(译者注:中文媒体称之为“中国娃娃”。)

王小亭

1937年

20世纪30年代蹂躏欧洲的帝国主义势力已经把触角伸向了亚洲,但是很多美国人依然在考虑是否要介入这个远在天边陌生国度的武装冲突。当日本军队的铁蹄在1937年夏天踏过上海时,这个观点逐渐发生了变化。战争开始于8月,不间断和空袭和轰炸造成了市区的巨大恐慌和伤亡。但是其它国家对于受害者不屑一顾,直到他们看到了8月28日日本轰炸机所造成的破坏。赫斯特新闻摄影师王小亭——绰号“新闻短片”——来到遭到破坏的上海南站,他描述刚刚过去的大屠杀:“我的鞋被血水浸透了。”在一片废墟中,王看到一个大哭的中国男孩,他的母亲的尸体倒在旁边的铁轨上。他说他迅速拍完了相机里剩下的胶卷,然后把孩子抱到安全的地方,后来孩子的父亲冲过来,把孩子抱走。这张受伤、无助的婴儿的照片被传往纽约,出现在赫斯特新闻短片和《生活》杂志上——这是一张照片有可能被最多人看到的机会。1.36亿人看到了这张照片,它拨动了人们超越种族和地理范围的心弦。在很多人看来,婴儿的伤痛代表了中国的苦难和日本的杀戮欲。被称作“血腥星期六”的这张照片成为了有史以来最强大的新闻素材。它的作用证明了一张照片可以左右官方和民间态度的强大力量。王的照片让美国、英国和法国正式抗议攻击时间,同时西方民众的情绪开始倾向于介入这个导致第二次世界大战亚洲战场的事件。

温斯顿•丘吉尔

尤素福•卡什

1941年

1941年,英国孤立无援。当时,波兰、法国和大部分欧洲国家都落入纳粹党势力范围,只有这个小国的飞行员、士兵和水手英联邦成员国的一些人,牵制邪恶势力的兵力。温斯顿•丘吉尔坚定地认为英伦三岛的光芒必将继续闪耀。1941年12月,日本袭击珍珠港,让美国全面参加二战,丘吉尔到渥太华拜访议会,感谢加拿大和盟国的协助。丘吉尔不知道尤素福•卡什要给他拍一张照片。当他走出会议室看到这位出生在土耳其的加拿大摄影师时,他点燃一支雪茄,吐出一口烟说:“我怎么不知道?你只可以拍一张。”在卡什做准备时,丘吉尔拒绝拿掉含在嘴里的雪茄。卡什准备就绪之后,走到首相面前,说:“请原谅我,先生。”伸手拿走丘吉尔口中的雪茄。“当我走回照相机,他看起来怒火冲天,似乎要一口把我吞掉。就在这个时候,我按下了快门。”丘吉尔毕竟是个政治家,他笑着说:“你可以再拍一张。”他与卡什握了握手,对他说:“你有本事让一头咆哮的狮子摆好拍照的姿势。”

卡什驯狮天赋所带来的成果是一张历史上被传阅最多的照片,也形成了政治肖像照的分水岭。卡什那张斗牛犬式丘吉尔的照片首先发表在《美国午间新闻》上,最后登上《生活》杂志封面。它为当代摄影师打开了一扇大门,为领导人拍摄真实、甚至批判性的肖像照。

悲伤

德米特里•巴尔特曼茨

1942年

出生在波兰的德米特里•巴尔特曼茨本打算成为一名数学教师,但后来爱上了摄影。二战爆发时,他接到了他的老板从苏联政府报纸《消息报》打来的电话:“我们的军队明天将会跨越边境,准备好拍摄一些兼并西乌克兰的照片!”当时,苏联还把纳粹德国当作盟友。但是当阿道夫•希特勒与亲密战友反目成仇并入侵苏联之后,巴尔特曼茨的任务也发生了改变。在报道后来被称为伟大的卫国战争题材时,他既拍到了士兵享受短暂的休息时刻,也拍到了堆满尸体的道路。1942年1月,他来到新解放的城市克里米亚刻赤,两个月前,纳粹死亡小队包围了这座城市里的7000名犹太人。巴尔特曼茨在多年后回忆到:“他们把所有的家庭成员赶出来——女人、老人、孩子。把他们赶到反坦克壕沟里,向他们射击。”巴尔特曼茨看到了一片堆满尸体的地区,老年人和年轻人的尸体伸出双手,定格在最后一个乞求的姿势上。聚集在这里的城镇居民开始痛哭,他们挥舞着双手,其它人努力控制自己不表露出过分的悲伤。巴尔特曼茨已经无法接受更多这样的场景,他记录下看到的一切。但是,纳粹在苏联土地上大规模屠杀的图像对领导人来说具有太大的视觉冲击力了,他们担心这会过分宣扬人民的痛苦情绪。所以和他拍摄的很多其它照片一样,这张照片被禁止发布,直到60年代自由主义思想逐渐渗入到俄罗斯社会中。被公之于众之后,巴尔特曼茨的照片让几代人重新回忆起这场伟大的战争。他阴郁第说:“你尽力做好自己的工作,总有一天会有人看到。”

美国式哥特

戈登•帕克斯

1942年

作为堪萨斯州一个黑人佃农家庭的第15个孩子,戈登•帕克斯知道贫穷的滋味。但是,在他作为美国农场安全管理局的学者于1942年来到华盛顿之前,他从未体验过这里猖獗的种族主义情绪。作为《生活》杂志的第一位非裔美国摄影师,帕克斯震惊了。他说:“白人餐厅让我从后门进入,白人的剧院甚至都不让我进门。”帕克斯不愿被现实压倒,他到处寻找非裔美国人,记录他们如何面对无处不在的侮辱。这时他遇到了在美国农场安全管理局大楼里工作的艾拉•沃特森。她向他讲述了痛苦的生活;一个父亲被滥施私刑的暴徒杀;一个丈被枪击身亡。他在沃特森的一个正常工作日里给他拍了一张照片,成就了他的巅峰作品“美国式哥特”,明显是在效仿格兰特•伍德1937年标志性的油画。这是对非裔美国人出境的控诉,强调了“自由土地”上极大的不平等,成为了美国民权运动以前的标志性作品。帕克斯后来说:“相机的任务是曝光种族主义丑恶,展示最痛苦的人群。”

贝蒂•格莱宝

弗兰克•保沃尔尼

1943年

特洛伊的海伦,这位希腊神话中的半神引发了特洛伊战争和“数千艘船只的海战”,但她与来自圣路易斯的贝蒂•格莱宝没有什么关系。这位金发碧眼的好莱坞女明星有一双能激励美国士兵、水手、空军和海军的美腿,让他们敢于从轴心国的势力中拯救人类的文明。与海伦不同,贝蒂代表有血有肉的“家乡女孩”,不疾不徐地撩拨着男人的心。弗兰克•保沃尔尼把贝蒂送到军队中纯属偶然。作为一名二十世纪福克斯的摄影师,他负责为1943年的影片《舞台玫瑰》拍摄宣传照。贝蒂同意拍摄一张“后背照”。这家工作室把这张照片变成了最早期的流行海报,很快军队就开始每个月订购5万张海报。男人无论去到哪里,都把贝蒂带在身边,她的海报被贴在军营的墙上,被喷涂在轰炸机上,男人最贴近心窝的口袋里总有两三张她的照片。在玛丽莲•梦露出现之前,贝蒂的微笑和她的美腿——据说由伦敦劳埃德公司承保100万美元——凝聚了无数在战场上想家的年轻男人(其中就包括一个年轻人休•海夫纳,他说正是她的照片让她创办了《花花公子》)。格莱宝说:“我就是士兵的女孩。”战争期间,她每天都要在数百张海报上签字。“这就是这些士兵们的战争。”

原文:

Hitler at a Nazi Party Rally

Heinrich Hoffmann

1934

Spectacle was like oxygen for the Nazis, and Heinrich Hoffmann was instrumental in staging Hitler’s growing pageant of power. Hoffmann, who joined the party in 1920 and became Hitler’s personal photographer and confidant, was charged with choreographing the regime’s propaganda carnivals and selling them to a wounded German public. Nowhere did Hoffmann do it better than on September 30, 1934, in his rigidly symmetrical photo at the Bückeberg Harvest Festival, where the Mephistophelian Führer swaggers at the center of a grand Wagnerian fantasy of adoring and heiling troops. By capturing this and so many other extravaganzas, Hoffmann—who took more than 2 million photos of his boss—fed the regime’s vast propaganda machine and spread its demonic dream. Such images were all-pervasive in Hitler’s Reich, which shrewdly used Hoffman’s photos, the stark graphics on Nazi banners and the films of Leni Riefenstahl to make Aryanism seem worthy of godlike worship. Humiliated by World War I, punishing reparations and the Great Depression, a nation eager to reclaim its sense of self was rallied by Hitler’s visage and his seemingly invincible men aching to right wrongs. Hoffmann’s expertly rendered propaganda is a testament to photography’s power to move nations and plunge a world into war.

Migrant Mother

Dorothea Lange

1936

The picture that did more than any other to humanize the cost of the Great Depression almost didn’t happen. Driving past the crude “Pea-Pickers Camp” sign in Nipomo, north of Los Angeles, Dorothea Lange kept going for 20 miles. But something nagged at the photographer from the government’s Resettlement Administration, and she finally turned around. At the camp, the Hoboken, N.J.–born Lange spotted Frances Owens Thompson and knew she was in the right place. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother in the sparse lean-to tent, as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange later wrote. The farm’s crop had frozen, and there was no work for the homeless pickers, so the 32-year-old Thompson sold the tires from her car to buy food, which was supplemented with birds killed by the children. Lange, who believed that one could understand others through close study, tightly framed the children and the mother, whose eyes, worn from worry and resignation, look past the camera. Lange took six photos with her 4x5 Graflex camera, later writing, “I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment.” Afterward Lange informed the authorities of the plight of those at the encampment, and they sent 20,000 pounds of food. Of the 160,000 images taken by Lange and other photographers for the Resettlement Administration, Migrant Mother has become the most iconic picture of the Depression. Through an intimate portrait of the toll being exacted across the land, Lange gave a face to a suffering nation.

The Falling Soldier

Robert Capa

1936

Robert Capa made his seminal photograph of the Spanish Civil War without ever looking through his viewfinder. Widely considered one of the best combat photographs ever made, and the first to show battlefield death in action, Capa said in a 1947 radio interview that he was in the trenches with Republican militiamen. The men would pop aboveground to charge and fire old rifles at a machine gun manned by troops loyal to Francisco Franco. Each time, the militiamen would get gunned down. During one charge, Capa held his camera above his head and clicked the shutter. The result is an image that is full of drama and movement as the shot soldier tumbles backward.

In the 1970s, decades after it was published in the French magazine Vu and LIFE, a South African journalist named O.D. Gallagher claimed that Capa had told him the image was staged. But no confirmation was ever presented, and most believe that Capa’s is a genuine candid photograph of a Spanish militiaman being shot. Capa’s image elevated war photography to a new level long before journalists were formally embedded with combat troops, showing how crucial, if dangerous, it is for photographers to be in the middle of the action.

Fort Peck Dam

Margaret Bourke-White

1936

It was to quickly become the most influential news and photography magazine of its time, and LIFE’s November 1936 debut issue proudly announced that it would cover stories of enormous scope and complexity in a uniquely visual way. What better person, thought publisher Henry Luce, than his Fortune magazine photographer Margaret Bourke-White to shoot LIFE’s premier story, on the construction of Montana’s Fort Peck Dam? There, on the cover with the castle-like structure and a photo essay inside, Bourke-White used pictures to give a human feel to an article on the world’s largest earth-filled dam. She did this by focusing not only on the technical challenges of the massive New Deal project in the Missouri River Basin but also on the Wild West vibe in “the whole ramshackle town,” a place “stuffed to the seams with construction men, engineers, welders, quack doctors, barmaids, fancy ladies.” Bourke-White’s cover became the defining image of the magazine that helped define a style of photojournalism and set the tone for the other great LIFE photographers who followed her. As her colleague Carl Mydans, the great war photojournalist, put it, Bourke-White’s influence “was incalculable.”

The Hindenburg Disaster

Sam Shere

1937

Zeppelins were majestic skyliners, luxurious behemoths that signified wealth and power. The arrival of these ships was news, which is why Sam Shere of the International News Photos service was waiting in the rain at the Lakehurst, N.J., Naval Air Station on May 6, 1937, for the 804-foot-long LZ 129 Hindenburg to drift in from Frankfurt. Suddenly, as the assembled media watched, the grand ship’s flammable hydrogen caught fire, causing it to spectacularly burst into bright yellow flames and kill 36 people. Shere was one of nearly two dozen still and newsreel photographers who scrambled to document the fast-moving tragedy. But it is his image, with its stark immediacy and horrible grandeur, that has endured as the most famous—owing to its publication on front pages around the world and in LIFE and, more than three decades later, its use on the cover of the first Led Zeppelin album. The crash helped bring the age of the airships to a close, and Shere’s powerful photograph of one of the world’s most formative early air disasters persists as a cautionary reminder of how human fallibility can lead to death and destruction. Almost as famous as Shere’s photo is the anguished voice of Chicago radio announcer Herbert Morrison, who cried as he watched people tumbling through the air, “It is bursting into flames ... This is terrible. This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world ... Oh, the humanity!”

Bloody Saturday

H.S. Wong

1937

The same imperialistic desires festering in Europe in the 1930s had already swept into Asia. Yet many Americans remained wary of wading into a conflict in what seemed a far-off, alien land. But that opinion began to change as Japan’s army of the Rising Sun rolled toward Shanghai in the summer of 1937. Fighting started there in August, and the unrelenting shelling and bombing caused mass panic and death in the streets. But the rest of the world didn’t put a face to the victims until they saw the aftermath of an August 28 attack by Japanese bombers. When H.S. Wong, a photographer for Hearst Metrotone News nicknamed Newsreel, arrived at the destroyed South Station, he recalled carnage so fresh “that my shoes were soaked with blood.” In the midst of the devastation, Wong saw a wailing Chinese baby whose mother lay dead on nearby tracks. He said he quickly shot his remaining film and then ran to carry the baby to safety, but not before the boy’s father raced over and ferried him away. Wong’s image of the wounded, helpless infant was sent to New York and featured in Hearst newsreels, newspapers and life magazine—the widest audience a picture could then have. Viewed by more than 136 million people, it struck a personal chord that transcended ethnicity and geography. To many, the infant’s pain represented the plight of China and the bloodlust of Japan, and the photo dubbed Bloody Saturday was transformed into one of the most powerful news pictures of all time. Its dissemination reveals the potent force of an image to sway official and public opinion. Wong’s picture led the U.S., Britain and France to formally protest the attack and helped shift Western sentiment in favor of wading into what would become the world’s second great war.

Winston Churchill

Yousuf Karsh

1941

Britain stood alone in 1941. By then Poland, France and large parts of Europe had fallen to the Nazi forces, and it was only the tiny nation’s pilots, soldiers and sailors, along with those of the Commonwealth, who kept the darkness at bay. Winston Churchill was determined that the light of England would continue to shine. In December 1941, soon after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was pulled into the war, Churchill visited Parliament in Ottawa to thank Canada and the Allies for their help. Churchill wasn’t aware that Yousuf Karsh had been tasked to take his portrait afterward, and when he came out and saw the Turkish-born Canadian photographer, he demanded to know, “Why was I not told?” Churchill then lit a cigar, puffed at it and said to the photographer, “You may take one.” As Karsh prepared, Churchill refused to put down the cigar. So once Karsh made sure all was ready, he walked over to the Prime Minister and said, “Forgive me, sir,” and plucked the cigar out of Churchill’s mouth. “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” Ever the diplomat, Churchill then smiled and said, “You may take another one” and shook Karsh’s hand, telling him, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.”

The result of Karsh’s lion taming is one of the most widely reproduced images in history and a watershed in the art of political portraiture. It was Karsh’s picture of the bulldoggish Churchill—published first in the American daily PM and eventually on the cover of LIFE—that gave modern photographers permission to make honest, even critical portrayals of our leaders.

Grief

Dmitri Baltermants

1942

The Polish-born Dmitri Baltermants had planned to be a math teacher but instead fell in love with photography. Just as World War II broke out, he got a call from his bosses at the Soviet government paper Izvestia: “Our troops are crossing the border tomorrow. Get ready to shoot the annexation of western Ukraine!” At the time the Soviet Union considered Nazi Germany its ally. But after Adolf Hitler turned on his comrades and invaded the Soviet Union, Baltermants’ mission changed too. Covering what then became known as the Great Patriotic War, he captured grim images of body-littered roads along with those of troops enjoying quiet moments. In January 1942 he was in the newly liberated city of Kerch, Crimea, where two months earlier Nazi death squads had rounded up the town’s 7,000 Jews. “They drove out whole families—women, the elderly, children,” Baltermants recalled years later. “They drove all of them to an antitank ditch and shot them.” There Baltermants came upon a bleak, corpse-choked field, the outstretched limbs of old and young alike frozen in the last moment of pleading. Some of the gathered townspeople wailed, their arms wide. Others hunched in paroxysms of grief. Baltermants, who witnessed more than his share of death, recorded what he saw. Yet these images of mass Nazi murders on Soviet soil were too graphic for his nation’s leaders, wary of displaying the suffering of their people. Like many of Baltermants’ photos, this one was censored, being shown only decades later as liberalism seeped into Russian society in the 1960s. When it finally emerged, Baltermants’ picture allowed generations of Russians to form a collective memory of their great war. “You do your work the best you can,” he somberly observed, “and someday it will surface.”

American Gothic

Gordon Parks

1942

As the 15th child of black Kansas sharecroppers, Gordon Parks knew poverty. But he didn’t experience virulent racism until he arrived in Washington in 1942 for a fellowship at the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Parks, who would go on to became the first African-American photographer at LIFE, was stunned. “White restaurants made me enter through the back door. White theaters wouldn’t even let me in the door,” he recalled. Refusing to be cowed, Parks searched out older African Americans to document how they dealt with such daily indignities and came across Ella Watson, who worked in the FSA’s building. She told him of her life of struggle, of a father murdered by a lynch mob, of a husband shot to death. He photographed Watson as she went about her day, culminating in his American Gothic, a clear parody of Grant Wood’s iconic 1930 oil painting. It served as an indictment of the treatment of African Americans by accentuating the inequality in “the land of the free” and came to symbolize life in pre-civil-rights America. “What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism,” Parks later observed, “by showing the people who suffered most under it.”

Betty Grable

Frank Powolny

1943

Helen of Troy, the mythic Greek demigod who sparked the Trojan War and “launch’d a thousand ships,” had nothing on Betty Grable of St. Louis. For that platinum blond, blue-eyed Hollywood starlet had a set of gams that inspired American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines to set forth to save civilization from the Axis powers. And unlike Helen, Betty represented the flesh-and-blood “girl back home,” patiently keeping the fires burning. Frank Powolny brought Betty to the troops by accident. A photographer for 20th Century Fox, he was taking publicity pictures of the actress for the 1943 film Sweet Rosie O’Grady when she agreed to a “back shot.” The studio turned the coy pose into one of the earliest pinups, and soon troops were requesting 50,000 copies every month. The men took Betty wherever they went, tacking her poster to barrack walls, painting her on bomber fuselages and fastening 2-by-3 prints of her next to their hearts. Before Marilyn Monroe, Betty’s smile and legs—said to be insured for a million bucks with Lloyd’s of London—rallied countless homesick young men in the fight of their lives (including a young Hugh Hefner, who cited her as an inspiration for Playboy). “I’ve got to be an enlisted man’s girl,” said Grable, who signed hundreds of her pinups each month during the war. “Just like this has got to be an enlisted man’s war.”

|

|