|

|

【中文标题】一百张最有影响力的照片 之四

【原文标题】Most Influential Photos

【登载媒体】时代周刊

【原文作者】Ben Goldberger

【原文链接】http://100photos.time.com/photos/harold-edgerton-milk-drop

华沙投降的犹太男孩

摄影师不详

1943年

照片中这个心怀恐惧、举起双手的小男孩,是被集中在华沙犹太人区的50万名犹太人之一。这片街区被纳粹党改造成一个用围墙环绕的充满了饥饿和死亡的地带。从1942年7月开始,德国占领军开始每天把5000名华沙居民送入集中营。当种族灭绝的消息传来,这里的居民组建了一支抵抗组织。年轻的组织领导人默德采•阿涅莱维奇写到:“我们认为自己是命运悲惨的地下犹太人,我们的时间就要到了,没有希望,也没有救援。”1943年4月19日,时间终于到了。当纳粹军队开始抓铺其余的犹太人时,装备可怜的爱国者奋起抵抗,但最终被德国坦克和喷火兵镇压。起义于5月16日结束,5.6万名幸存者面临被处决或者流放到集中营和劳改营的命运。纳粹党卫军少将于尔根•斯特鲁普对于自己清理犹太人区的工作甚感骄傲,他制作了一份“斯特里普报告”。这份牛皮封面的粘贴簿有75页,包括一个自吹自擂的战利品清单、每日杀人数量和数十张令人心痛的照片,其中就有男孩举起双手的照片。这份文件证明了他的罪行,不但让那些冢中枯骨有了本来的面容,这些照片还显示了摄影作为记录手段的力量。在纽伦堡战犯审判中,这个粘贴簿作为指证斯特里普的关键证据,让他在1951年犹太人区附近被处以绞刑。大屠杀过程中有很多让人不忍卒视的照片,但都没有投降的男孩的照片那样强大的证据价值。男孩的身份无从考证,只能代表600万被纳粹杀害的手无寸铁的犹太人。

批判者

维加

1943年

亚瑟•费利格用一双敏锐的眼睛来捕捉生活中的不公。这位澳大利亚移民生长在纽约下东区贫穷的街道,费利格后来被称为“维加”——脱胎于“显灵板”的发音——原因是他异乎寻常的捕捉精彩瞬间的能力。他所拍摄的大多是犯罪现场、惨剧和纽约居民夜生活的照片。1943年,维加把他的相机闪光灯对准了大萧条之后社会经济不平等的现象。他并不讨厌摆拍,他请他的助手路易•利奥塔到鲍厄里去找一个女醉汉。他找到了一个愿意配合工作的人,把她带到大都市歌剧院60周年庆典的现场。利奥塔让她在入口处等待,维加也在那里等待乔治•华盛顿•卡瓦纳夫和德希斯夫人,这两位贵妇经常会出现在报刊的名流动向栏目。当两位戴着头饰、身穿皮毛大衣的头面人物出现时,维加让利奥塔放出醉汉。利奥塔回忆到:“就像一场爆炸,连续三、四次闪光差点让我的眼睛瞎掉。”在闪光灯下,维加捕捉到巨大的财富与肮脏的贫穷间赤裸裸的对比,这种“我抓到你了”摄影风格所带来的商业利益带动了几十年后自由摄影师职业的发展。这张照片出现在《生活》杂志封面,标题是“时尚人群”,文章中说两位女人的亮相“引来了旁观者厌恶的目光”。“批判者”后来被揭露为摆拍,但并没有削弱其影响力。

登陆日

罗伯特•卡帕

1944年

这是一场为拯救人类文明而发动的入侵,《生活》杂志的罗伯特•卡帕就在现场,他是唯一一名在登陆日与34250名士兵一起跋涉过奥马哈海滩的摄影师。他的照片充满了残忍战争中不和谐的运动效果,让公众了解到美国士兵眼中的危险战争。照片中的士兵是一等兵哈斯顿•莱利,在纳粹德国的炮弹击中登陆舰之后,他跳入水中。海水很深,他不得不在水下步行,直到一口气缓不过来。他启动了海军M26救生腰带,浮上水面,立即成为机枪和火炮的目标。在多次冲锋受阻之后,这位22岁的士兵花了大约半个小时才到达诺曼底海滩。卡帕拍摄了一张他浸在浪花中的照片,之后一位中士过来帮助莱利。这位中士在后来说:“这个家伙在这里干什么?我简直不敢相信,海滩上有一个摄影师。”卡帕在敌人的攻击下挣扎了一个半小时,周围的人纷纷阵亡。后来,一名传令兵把他拍摄的4卷胶卷送到《生活》杂志伦敦办公室。杂志的总裁立即停止印刷现有的杂志,把这张照片放到6月19日出版的刊物中。卡帕拍摄的大部分照片都没有影像,只有部分留存下来。剩下的那些照片画面粗糙、模糊,但给人一种军事行动中的疯狂感,让我们对那次全世界都被卷入的冲突留下了深刻的记忆。

硫黄岛升旗

乔•罗森塔尔

1945年

那是一个东京以南760英里处的一个小岛,一个火山堆积岩形成的岛屿,阻断了盟军向日本进攻的路线。美国人需要把硫黄岛改造成一个空军基地,但是日本军队驻扎了重兵防守。美军在1945年2月19日登陆,为期一个月的战役导致6800名美国士兵和2.1万名日本士兵丧生。在战争开始的第五天,海军陆战队占领了摺钵山。他们很快竖起了一面美国国旗,但是指挥官要求一面更大的旗帜,以鼓励士兵,震慑敌人。美联社摄影师乔•罗森塔尔带着沉重的照相机爬到山顶,当5名海军陆战队员和一名海军医护兵准备竖起星条旗时,罗森塔尔向后退了几部步,以便更好地取景,他差点错过了这个瞬间。对于这张战争期间最为著名的照片,他后来写到:“天空乌云密布,风把旗帜在这群人的头顶展开。他们脚下杂乱的地形和成堆的灌木丛凸显了战争的残酷。”两天后,罗森塔尔的照片出现在美国各家媒体的封面,很快成为这场战争中把人们团结起来的标志。这张照片为罗森塔尔赢得了普利策奖,它的影响如此深远,以至于被制成邮票和一座重达100吨的黄铜纪念碑。

德国国会大厦升旗

叶夫根尼•哈尔杰伊

1945年

“我等待了1400天,就是为了现在这一刻。”1945年5月2日,乌克兰出生的叶夫根尼•哈尔杰伊望着柏林的废墟说。经历了4年在东欧的转战和摄影之后,这位红军士兵终于来到了纳粹德国的心脏。他随身携带着一部莱卡三型相机和一面巨大的苏联国旗,那是他的裁缝叔叔用三块红色桌布拼起来的。阿道夫•希特勒两天前已经自杀,但是当哈尔杰伊进军国会大厦时,依然遇到了顽强的抵抗。他让三名士兵帮助他,他们爬上摇摇欲坠的台阶,爬过国会大厦楼顶浸满鲜血的矮墙。哈尔杰伊透过镜头,知道他终于拍到了渴望已久的画面:“我太兴奋了。”在洗照片时,哈尔杰伊为了突出照片的效果,加强了烟雾的色彩,让天空变得更阴沉,甚至掩盖了一些负面的内容,以便营造一个部分真实、部分人造,但全部充满爱国情绪的浪漫景象。这张照片发表在《星火》杂志上之后,立即成为宣传的工具。不出意外,插在敌人心脏地带的旗帜彰显了共产主义的高贵地位,确立了苏联的霸主姿态。并且暗示,在战争的大幕拉下之后,约瑟夫•斯大林总理即将升起冷战的铁幕。

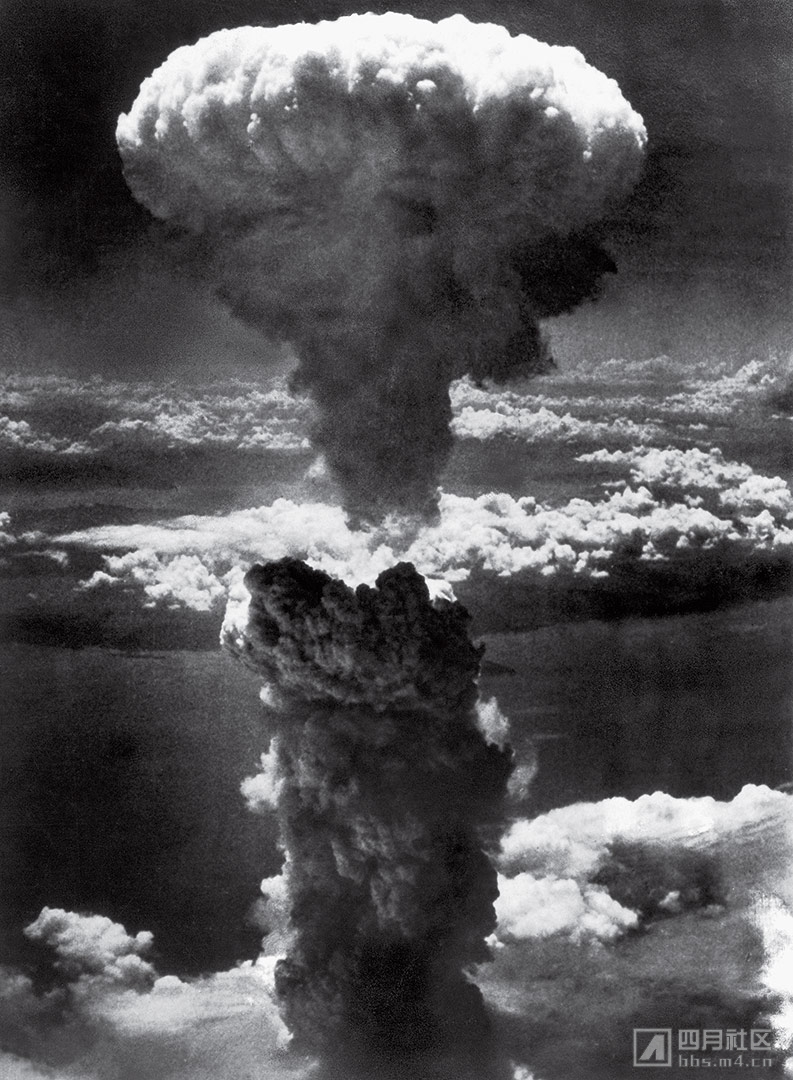

长崎上空的蘑菇云

查尔斯•莱菲中尉

1945年

绰号为小男孩的原子弹在日本广岛引爆三天之后,美军在长崎投下一颗具有更大威力的原子弹——胖子。爆炸激起高达4.5万英尺高的放射尘埃和废墟。负责投弹的查尔斯•莱菲中尉说:“我们看到这个巨大的尘埃不断上升,直冲上天。”他被两万当量级的武器威力惊得目瞪口呆。“有紫色、红色、白色,各种颜色……就像一杯煮开的咖啡,好像一个生命体。”他连续拍摄了16张照片,炸弹可怕的威力瞬间夺走了这座城市浦上河畔8万人的生命。6天之后,这两枚炸弹迫使裕仁天皇宣布日本无条件投降。官方禁止发布原子弹巨大破坏力的照片,但是莱菲的照片——唯一一张从天空全景显示蘑菇云的照片——广为流传。它让美国人开始热衷于核武器,整个国家兴致勃勃地进入了原子时代。同时再一次证明,历史是由胜利者书写的。

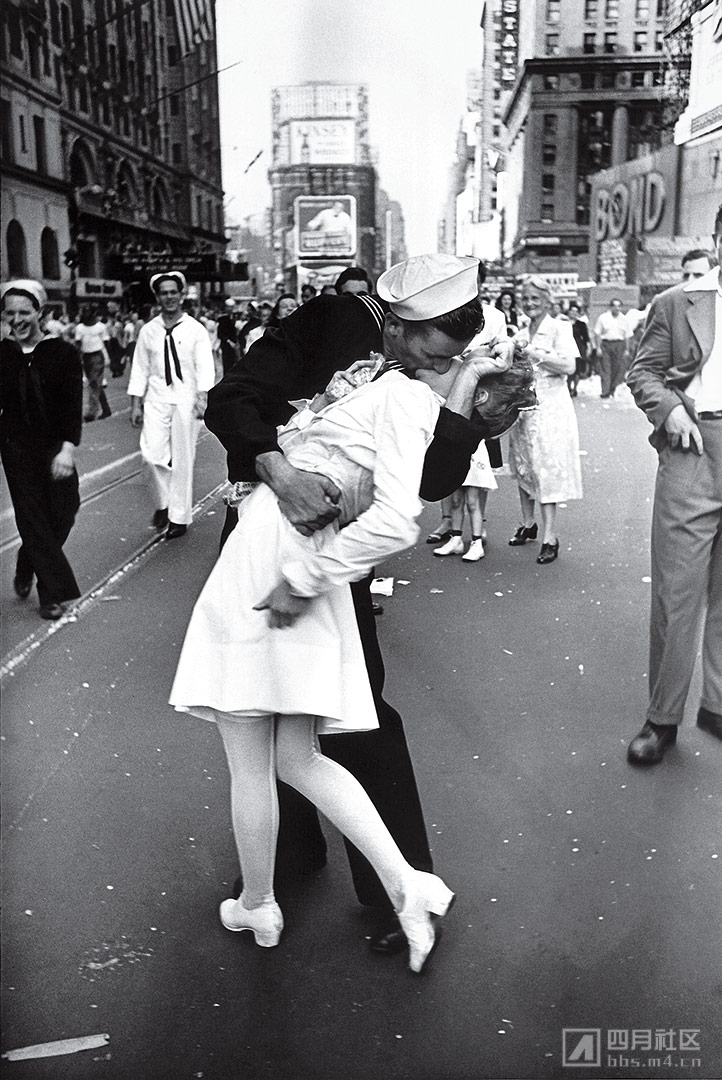

时代广场上的对日战争胜利日

阿尔弗雷德•艾森斯塔特

1945年

摄影的至高使命是抓住转瞬即逝的瞬间,留住生活中的希望、痛苦、疑惑和喜悦。阿尔弗雷德•艾森斯塔特作为最早在《生活》杂志任职的四名摄影师之一,把“寻找并捕捉有丰富内涵的瞬间”作为自己的使命。当二战在1945年8月14日结束时,他不需要到更远的地方去达成自己的使命。他走在纽约市的街道上,很快发现自己置身于时代广场欢乐的喧嚣声中。他在寻找拍摄的目标,这时前面的一名水手拉过一位护士,把她的腰弯下来亲吻她。艾森斯塔特这张充满激情的照片,浓缩了人们在这具有纪念意义的一天里放松的情绪和对未来的期许,释放在一个无拘无束的欢乐气氛中(尽管有人会说,放在今天这就是性骚扰)。这张亮丽的照片成为了20世纪最著名、拷贝最多的图片,让我们永远记住了改变世界历史的那个时刻。艾森斯塔特说:“人们告诉我,当我进入天堂,他们还会记得这张照片。”

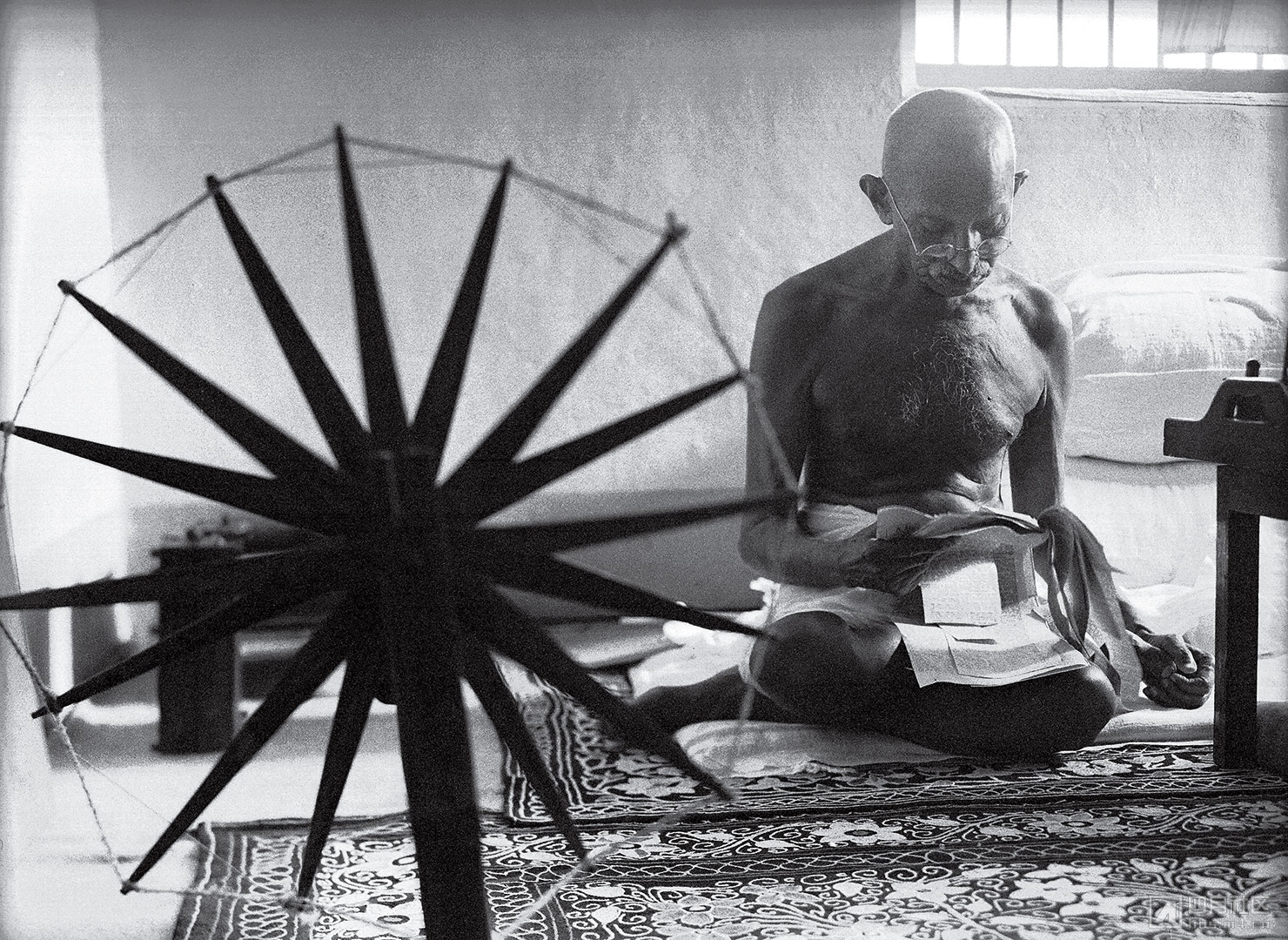

甘地和纺车

玛格丽特•博克•怀特

1946年

英国人从1932年到1933年把默罕达斯•甘地监禁在印度浦那耶拉夫达监狱中,这位民族运动领导人用一架纺车纺线做衣。这个举动,从被监禁期间个人的自我宽慰行为,演化成独立运动的试金石,甘地鼓励他的同胞自己纺线制衣,不要去买英国人的东西。当玛格丽特•博克•怀特前来采访甘地有关印度领袖问题时,纺车与甘地的身份已经密不可分。他的秘书普亚雷拉•纳亚尔说,她在给甘地拍照之前,必须学会如何纺线。博克•怀特拍摄的甘地坐在纺车旁阅读新闻的照片,并没有出现在她的报道文章里。但是不到两年之后,这张照片连同一张颂扬文章在甘地被刺杀后得到发表。立即成为了人们挥之不去的记忆,被杀害的民权人士、不屈服的十字军战士、强大的象征,让印度次大陆之外的人把甘地看作一个崇尚和平的圣人。

原子的达利

菲力佩•哈尔斯曼

1948年

捕捉拍摄对象的精髓是菲力佩•哈尔斯曼毕生致力的工作。所以当哈尔斯曼准备去拍摄他的好友和长期以来的合作伙伴、超现实主义画家萨尔瓦多•达利时,他知道一个简单的坐姿照是远远不够的。受达利的作品雷达阿朵米卡的启发,哈尔斯曼围绕这位艺术家设计了一个复杂的场景,包括一张原作品、由细线悬挂的一张椅子和一个画板。哈尔斯曼的妻子和女儿艾琳作为助理站在镜头外,摄影师一声令下,他们把三只猫和一桶水丢到画面里,达利同时双脚起跳。这只临时拼凑的摄影团队拍摄了26次才达到令哈尔斯曼满意的画面。不出意料,最终发表在《生活》杂志上的照片让人们开始欣赏达利的作品。这位艺术家甚至在照片发表前直接在上面画了一副画。

在哈尔斯曼之前,肖像摄影作品往往显得僵硬、模糊,摄影师与拍摄对象明显没有交流。哈尔斯曼精准对焦拍摄对象——比如阿尔伯特•爱因斯坦、玛丽莲•梦露和阿尔弗雷德•希区柯克——在移动中按下快门。他重新定义了肖像照的概念,让后世摄影师与拍摄对象更好地交流。

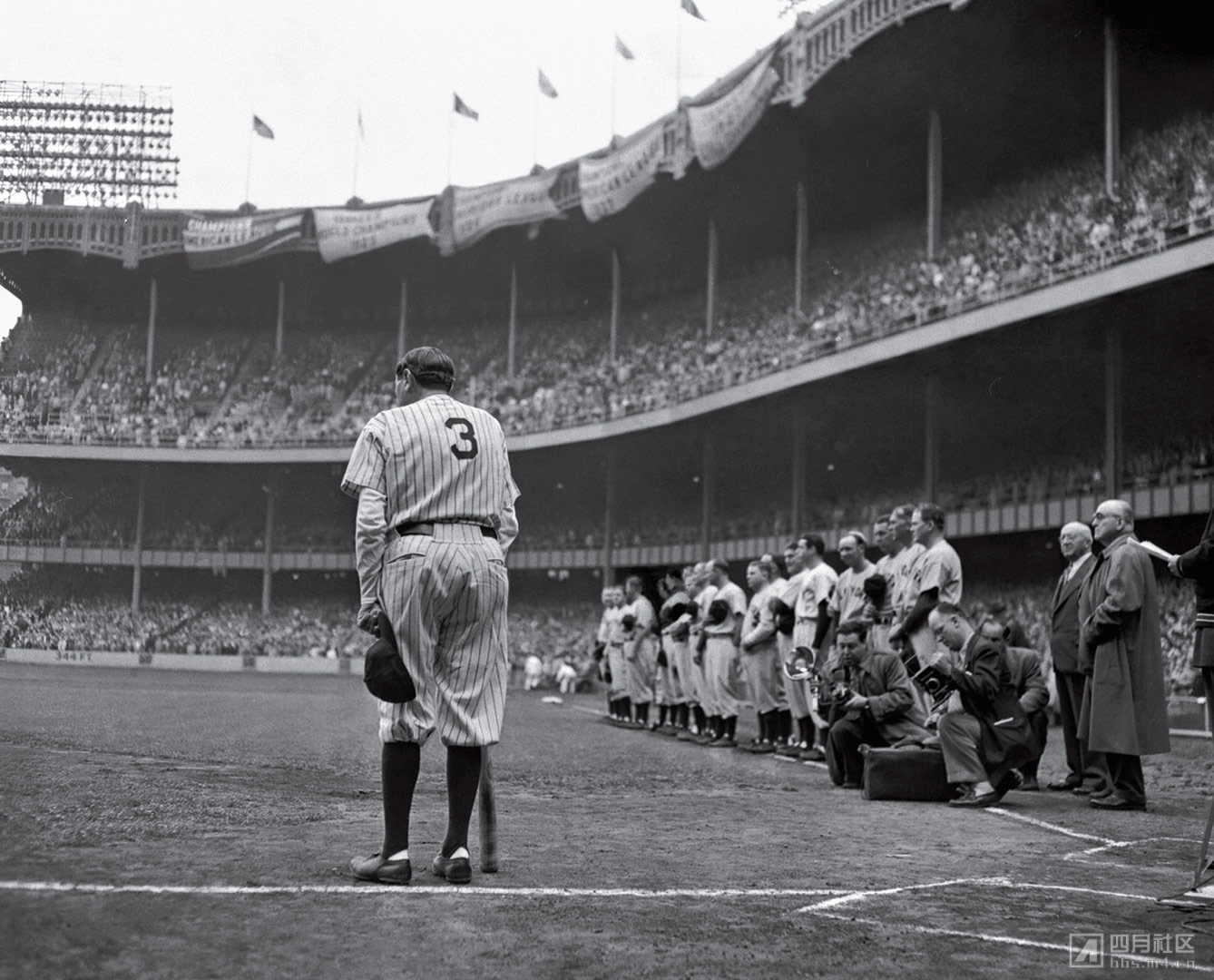

贝比引退

耐特•费恩

1948年

他是有史以来最伟大的棒球手、全垒打之王。但是到了1948年,贝比•鲁斯已经离开赛场十年之久,在与癌症晚期艰难地斗争。当人们敬爱的巴比诺(鲁斯的昵称)在6月13日站在人群面前庆祝洋基体育馆——所有人都知道它的另一个名字是“鲁斯的房子”——建立二十五周年,并让3号球衣正式退役时,人们都知道这是他最后一次告别。

《纽约先驱论坛报》的耐特•费恩与数十名摄影师站在一垒线后面。当国歌响起,费恩“有一种感觉”,他走到鲁斯背后,看到这位骄傲的棒球手靠在球棒上,瘦弱的双腿说明疾病已经极度削弱了他的身体。从那个角度,费恩捕捉到了近现代运动场上神话般的人物照片——即使他们已经虚弱不堪,但气场依旧强大。两个月之后,鲁斯去世了,费恩因为这张照片获得了普利策奖。这是普利策奖第一次授予体育摄影师,为传统新闻摄影之外的领域开辟了一片天空。

原文:

Jewish Boy Surrenders in Warsaw

Unknown

1943

The terrified young boy with his hands raised at the center of this image was one of nearly half a million Jews packed into the Warsaw ghetto, a neighborhood transformed by the Nazis into a walled compound of grinding starvation and death. Beginning in July 1942, the German occupiers started shipping some 5,000 Warsaw inhabitants a day to concentration camps. As news of exterminations seeped back, the ghetto’s residents formed a resistance group. “We saw ourselves as a Jewish underground whose fate was a tragic one,” wrote its young leader Mordecai Anielewicz. “For our hour had come without any sign of hope or rescue.” That hour arrived on April 19, 1943, when Nazi troops came to take the rest of the Jews away. The sparsely armed partisans fought back but were eventually subdued by German tanks and flamethrowers. When the revolt ended on May 16, the 56,000 survivors faced summary execution or deportation to concentration and slave-labor camps. SS Major General Jürgen Stroop took such pride in his work clearing out the ghetto that he created the Stroop Report, a leather-bound victory album whose 75 pages include a laundry list of boastful spoils, reports of daily killings and dozens of heart-wrenching photos like that of the boy raising his hands. This collection proved his undoing, for besides giving a face to those who died, the pictures reveal the power of photography as a documentary tool. At the subsequent Nuremburg war-crimes trials, the volume became key evidence against Stroop and resulted in his hanging near the ghetto in 1951. The Holocaust produced scores of searing images. But none had the evidentiary impact of the boy’s surrender. The child, whose identity has never been confirmed, has come to represent the face of the 6 million defenseless Jews killed by the Nazis.

The Critic

Weegee

1943

Arthur Fellig had a sharp eye for the unfairness of life. An Austrian immigrant who grew up on the gritty streets of New York City’s Lower East Side, Fellig became known as Weegee—a phonetic take on Ouija—for his preternatural ability to get the right photo. Often these were film-noirish images of crime, tragedy and the denizens of nocturnal New York. In 1943, Weegee turned his Speed Graphic camera’s blinding flash on the social and economic inequalities that lingered after the Great Depression. Not averse to orchestrating a shot, he dispatched his assistant, Louie Liotta, to a Bowery dive in search of an inebriated woman. He found a willing subject and took her to the Metropolitan Opera House for its Diamond Jubilee celebration. Then Liotta set her up near the entrance while Weegee watched for the arrival of Mrs. George Washington Kavanaugh and Lady Decies, two wealthy women who regularly graced society columns. When the tiara- and fur-bedecked socialites arrived for the opera, Weegee gave Liotta the signal to spring the drunk woman. “It was like an explosion,” Liotta recalled. “I thought I went blind from the three or four flash exposures.” With that flash, Weegee captured the stark juxtaposition of fabulous wealth and dire poverty, in a gotcha style that anticipated the commercial appeal of paparazzi decades later. The photo appeared in life under the headline “The Fashionable People,” and the piece let readers know how the women’s “entry was viewed with distaste by a spectator.” That The Critic was later revealed to have been staged did little to dampen its influence.

D-Day

Robert Capa

1944

It was the invasion to save civilization, and LIFE’s Robert Capa was there, the only still photographer to wade with the 34,250 troops onto Omaha Beach during the D-Day landing. His photographs—infused with jarring movement from the center of that brutal assault—gave the public an American soldier’s view of the dangers of war. The soldier in this case was Private First Class Huston Riley, who after the Nazis shelled his landing craft jumped into water so deep that he had to walk along the bottom until he could hold his breath no more. When he activated his Navy M-26 belt life preservers and floated to the surface, Riley became a target for the guns and artillery shells mowing down his comrades. Struck several times, the 22-year-old soldier took about half an hour to reach the Normandy shore. Capa took this photo of him in the surf and then with the assistance of a sergeant helped Riley, who later recalled thinking, “What the hell is this guy doing here? I can’t believe it. Here’s a cameraman on the shore.” Capa spent an hour and a half under fire as men around him died. A courier then transported his four rolls of film to LIFE’s London offices, and the magazine’s general manager stopped the presses to get them into the June 19 issue. Most of the film, though, showed no images after processing, and only some frames survived. The remaining images have a grainy, blurry look that gives them the frenetic feel of action, a quality that has come to define our collective memory of that epic clash.

Flag Raising on Iwo Jima

Joe Rosenthal

1945

It is but a speck of an island 760 miles south of Tokyo, a volcanic pile that blocked the Allies’ march toward Japan. The Americans needed Iwo Jima as an air base, but the Japanese had dug in. U.S. troops landed on February 19, 1945, beginning a month of fighting that claimed the lives of 6,800 Americans and 21,000 Japanese. On the fifth day of battle, the Marines captured Mount Suribachi. An American flag was quickly raised, but a commander called for a bigger one, in part to inspire his men and demoralize his opponents. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal lugged his bulky Speed Graphic camera to the top, and as five Marines and a Navy corpsman prepared to hoist the Stars and Stripes, Rosenthal stepped back to get a better frame—and almost missed the shot. “The sky was overcast,” he later wrote of what has become one of the most recognizable images of war. “The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.” Two days later Rosenthal’s photo was splashed on front pages across the U.S., where it was quickly embraced as a symbol of unity in the long-fought war. The picture, which earned Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize, so resonated that it was made into a postage stamp and cast as a 100-ton bronze memorial.

Raising a Flag over the Reichstag

Yevgeny Khaldei

1945

“This is what I was waiting for for 1,400 days,” the Ukrainian-born Yevgeny Khaldei said as he gazed at the ruins of Berlin on May 2, 1945. After four years of fighting and photographing across Eastern Europe, the Red Army soldier arrived in the heart of the Nazis’ homeland armed with his Leica III rangefinder and a massive Soviet flag that his uncle, a tailor, had fashioned for him from three red tablecloths. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide two days before, yet the war still raged as Khaldei made his way to the Reichstag. There he told three soldiers to join him, and they clambered up broken stairs onto the parliament building’s blood-soaked parapet. Gazing through his camera, Khaldei knew he had the shot he had hoped for: “I was euphoric.” In printing, Khaldei dramatized the image by intensifying the smoke and darkening the sky—even scratching out part of the negative—to craft a romanticized scene that was part reality, part artifice and all patriotism. Published in the Russian magazine Ogonek, the image became an instant propaganda icon. And no wonder. The flag jutting from the heart of the enemy exalted the nobility of communism, proclaimed the Soviets the new overlords and hinted that by lowering the curtain of war, Premier Joseph Stalin would soon hoist a cold new iron one across the land.

Mushroom Cloud Over Nagasaki

Lieutenant Charles Levy

1945

Three days after an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy obliterated Hiroshima, Japan, U.S. forces dropped an even more powerful weapon dubbed Fat Man on Nagasaki. The explosion shot up a 45,000-foot-high column of radioactive dust and debris. “We saw this big plume climbing up, up into the sky,” recalled Lieutenant Charles Levy, the bombardier, who was knocked over by the blow from the 20-kiloton weapon. “It was purple, red, white, all colors—something like boiling coffee. It looked alive.” The officer then shot 16 photographs of the new weapon’s awful power as it yanked the life out of some 80,000 people in the city on the Urakami River. Six days later, the two bombs forced Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s unconditional surrender in World War II. Officials censored photos of the bomb’s devastation, but Levy’s image—the only one to show the full scale of the mushroom cloud from the air—was circulated widely. The effect shaped American opinion in favor of the nuclear bomb, leading the nation to celebrate the atomic age and proving, yet again, that history is written by the victors.

V-J Day in Times Square

Alfred Eisenstaedt

1945

At its best, photography captures fleeting snippets that crystallize the hope, anguish, wonder and joy of life. Alfred Eisenstaedt, one of the first four photographers hired by LIFE magazine, made it his mission “to find and catch the storytelling moment.” He didn’t have to go far for it when World War II ended on August 14, 1945. Taking in the mood on the streets of New York City, Eisenstaedt soon found himself in the joyous tumult of Times Square. As he searched for subjects, a sailor in front of him grabbed hold of a nurse, tilted her back and kissed her. Eisenstaedt’s photograph of that passionate swoop distilled the relief and promise of that momentous day in a single moment of unbridled joy (although some argue today that it should be seen as a case of sexual assault). His beautiful image has become the most famous and frequently reproduced picture of the 20th century, and it forms the basis of our collective memory of that transformative moment in world history. “People tell me that when I’m in heaven,” Eisenstaedt said, “they will remember this picture.”

Gandhi and the Spinning Wheel

Margaret Bourke-White

1946

When the British held Mohandas Gandhi prisoner at Yeravda prison in Pune, India, from 1932 to 1933, the nationalist leader made his own thread with a charkha, a portable spinning wheel. The practice evolved from a source of personal comfort during captivity into a touchstone of the campaign for independence, with Gandhi encouraging his countrymen to make their own homespun cloth instead of buying British goods. By the time Margaret Bourke-White came to Gandhi’s compound for a life article on India’s leaders, spinning was so bound up with Gandhi’s identity that his secretary, Pyarelal Nayyar, told Bourke-White that she had to learn the craft before photographing the leader. Bourke-White’s picture of Gandhi reading the news alongside his charkha never appeared in the article for which it was taken, but less than two years later life featured the photo prominently in a tribute published after Gandhi’s assassination. It soon became an indelible image, the slain civil-disobedience crusader with his most potent symbol, and helped solidify the perception of Gandhi outside the subcontinent as a saintly man of peace.

Dalí Atomicus

Philippe Halsman

1948

Capturing the essence of those he photographed was Philippe Halsman’s life’s work. So when Halsman set out to shoot his friend and longtime collaborator the Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, he knew a simple seated portrait would not suffice. Inspired by Dalí’s painting Leda Atomica, Halsman created an elaborate scene to surround the artist that included the original work, a floating chair and an in-progress easel suspended by thin wires. Assistants, including Halsman’s wife and young daughter Irene, stood out of the frame and, on the photographer’s count, threw three cats and a bucket of water into the air while Dalí leaped up. It took the assembled cast 26 takes to capture a composition that satisfied Halsman. And no wonder. The final result, published in LIFE, evokes Dalí’s own work. The artist even painted an image directly onto the print before publication.

Before Halsman, portrait photography was often stilted and softly blurred, with a clear sense of detachment between the photographer and the subject. Halsman’s approach, to bring subjects such as Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe and Alfred Hitchcock into sharp focus as they moved before the camera, redefined portrait photography and inspired generations of photographers to collaborate with their subjects.

The Babe Bows Out

Nat Fein

1948

He was the greatest ballplayer of them all, the towering Sultan of Swat. But by 1948, Babe Ruth had been out of the game for more than a decade and was struggling with terminal cancer. So when the beloved Bambino stood before a massive crowd on June 13 to help celebrate the silver anniversary of Yankee Stadium—known to all in attendance as the House That Ruth Built—and to retire his No. 3, it was clear this was a final public goodbye.

Nat Fein of the New York Herald Tribune was one of dozens of photographers staked out along the first-base line. But as the sound of “Auld Lang Syne” filled the stadium, Fein “got a feeling” and walked behind Ruth, where he saw the proud ballplayer leaning on a bat, his thin legs hinting at the toll the disease had wreaked on his body. From that spot, Fein captured the almost mythic role that athletes play in our lives—even at their weakest, they loom large. Two months later Ruth was dead, and Fein went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for his picture. It was the first one awarded to a sports photographer, giving critical legitimacy to a form other than hard-news reportage.

|

|