【原文标题】The Rural Poor Are Shut Out of China's Top School

【中文标题】中国的重点高校排斥贫困的乡村

【原文链接】http://www.newsweek.com/2010/08/21/the-rural-poor-are-shut-out-of-china-s-top-schools.html

【登载媒体】新闻周刊

【译者】连长

School of Hard Knocks China’s Ivy League is no place for peasants.

在磕磕碰碰中吸取教训,中国版常春藤联盟是没有农民的地方

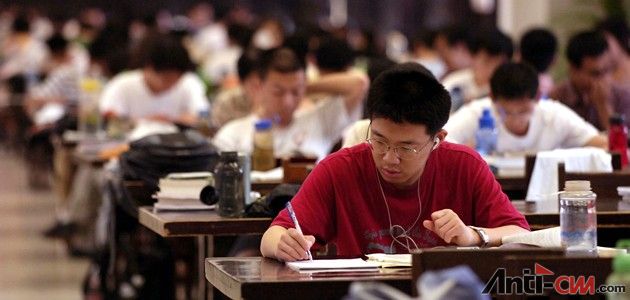

A student studies at a Tsinghua University library in Beijing, where poor and rural students are being excluded.

一位学生在北京的清华大学图书馆学习,贫困生和农村学生则被这所大学排除在外。

As China tries to graduate from the world’s factory to a nation with a strong middle class, its peasants still aren’t ready to make the leap. According to official statistics, China’s urban-rural income gap reached 3.33:1 in 2009, the widest since 1978, if not before. And as the gap increases, poor peasants are becoming marginalized in higher education, closing off one of their best opportunities for advancement. The trend is particularly alarming in Tsinghua and Peking universities, known as China’s MIT and Harvard respectively for their places atop China’s academic totem pole.

中国已经致力于从世界工厂转型为一个有着强大中产阶层的国家,但该国的农民仍然没有准备好跃进。据官方不久前的统计数据表明,2009年中国的城乡收入差距达到3.33:1,这是自1978年以来差距最大的。随着收入差距的拉大,贫困农民逐渐被高等教育边缘化,他们最好的发展机会之一也逐渐被封锁。尤其令人震惊的是清华大学和北京大学的这种趋势,清华大学和北京大学分别被誉为中国的麻省理工学院和哈佛,是中国最权威的学术图腾。

Students enrolling in those schools (both of which have some 30,000 students total) this September will find themselves in the overwhelming company of their urban peers. The most recent statistics published by China’s state-owned media showed that of China’s top two schools, Peking University had a rural population of 16.3 percent in 1999 (down from 50 percent to 60 percent in the 1950s), while Tsinghua University had a rural population of 17.6 percent in 2000. Both figures are from the most recent years in which any sort of dependable data have been published; experts and students alike agree that the numbers have shrunk even further since then. Pan Wei, a professor at the school of international studies at PKU, told the blog The China Beat that the number might be as low as 1 percent—a shocking statistic considering that more than half of China’s population is rural. “We can hardly find anyone here with a rural household registration,” Pan told NEWSWEEK. Media-relations officers at both schools did not answer calls for comment.

这些学校在今年9月招收的学生中(总计30000人),发现他们这群人中绝大多数是城市人口。最近由中国国家媒体公布的针对中国最好的两所高校的统计数据表明,1999年,北京大学的农村学生为16.3%(低于上世纪50年代的50%~60%),同样的,2000年清华大学的农村学生为17.6%.最新的这两组数据已经被公认为可靠数据;专家和学者均认同现在的数据与那时相比进一步缩小了。北京大学国际关系学院的潘维教授告诉博客传媒中国节拍(The China Beat),这个数据可能低于1%,考虑到中国有一半以上人口是农村人,这个统计数据将是令人震惊的。潘维告诉《新闻周刊》:“我们很难在这儿找到一个农村户口的人。”两所高校的媒体负责人没有对此事作出评论。

Across China, peasants make up 56 percent of the college-age population but only 50 percent of university students, mostly concentrated in China’s vocational schools or less prestigious universities. Yet the very top schools are the most skewed toward city residents. Why can’t peasants make it into elite universities? “Every rural area in China, including the outskirts of Beijing, lacks the educational resources of urban areas,” says Liu Hong, executive director of Peer China, a nonprofit organization that focuses on bringing educational equality to Chinese secondary schools.

在整个中国,大学适龄农村人口占了大约56%,然而,只有50%成了大学生,而且大多数集中在中国的职业院校或者不太重要的大学。最好的重点院校向城市居民倾斜。为什么农民不能够进入名牌大学?中国的一个皆在实现高中教育平等的非盈利组织负责人刘洪表示:“中国的所有农村地区,包括北京的郊区都缺乏像城市地区一样的教育资源。”

Traditionally, entrance to a university depended solely on an applicant’s score on a standardized test, called the Gaokao. But over the last five years or so, “China went into a different system that relied less on the Gaokao and started to allow for more monkeying with the system,” says James Z. Lee, dean of humanities and social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “If you’re fluent in French, you have a better chance of getting into a good university in China; that used to not be the case.” In other words, Chinese schools are copying Western ones that consider applicants in a more holistic way as they try to nurture well-rounded individuals instead of ace test takers. Yet, Liu says, “focusing on individuals widens the gap between urban and rural, because teachers in rural areas” can’t offer their students nearly as well-rounded an education as their urban counterparts can.

按照传统,进入一所大学完全取决于考生在被称为高考的标准化考试中的得分。但过去5年来,“中国进入了一个不同的体系,对高考不再那么看重了,允许一个更加灵活的体系,”香港科技大学人文社科学院院长詹姆斯·李如是说。“如果你会说一口流利的法语,你就会更有机会进入一个不错的中国大学(当然这仅仅是个例子)。”换句话说,中国的高校正在考虑复制西方的程序,更加全面的培养完善的个人,而不是考试王。然而,刘洪表示,将重点放在个人身上将会拉大城乡之间的差距,因为农村地区的教师不能为他们的学生提供像城市同龄人那样近乎全方位的教育。

The problems with peasant education are manifest. Farming villages aren’t great places to live, so they have a tough time attracting good teachers. In the experience of one educational NGO worker who works in rural China and asked to remain anonymous because of a company policy not to criticize China to the media, “Many teachers in rural areas who have college degrees actually only have them from continuing-education programs, which don’t really provide an education.” The aid worker described visiting rural schools and asking principals how many of their teachers have been to university: “The principals will say 100 percent, but if you dig a little deeper you’ll find out that someing like 20 percent have gone to university and the remaining 80 percent have degrees from these short-term programs.” Unsurprisingly, English-language teaching is especially bad. Although it’s required, Liu points out, “the middle-school English education is next to nothing; even the best students will have to have thorough remedial work in catch-up English.”

农民的教育难题是显而易见的。农村没有适合居住的地方,所以他们聘请优秀的教师极为艰难。 一些有在农村从事教育工作经历的非政府人员不愿透露姓名,因为他们的社交准则是不会当着媒体的面批评中国。“许多拥有大学学历的农村教师实际上只是持续教学课程,并不真正提供教育。”援助人员描述参观农村的学校,并询问校长有多少教师上过大学:“校长回答说100%,但如果你仔细观察,就会发现似乎只有20%上过大学的人愿意留下,其余80%只有短期的教学计划。”不出所料,英语教学特别糟糕。刘洪强调:“尽管英语是重点学科,但中学英语教学仍不充足,即便是最优秀的学生也要尽一切补救措施赶上英语。”

What’s more, as wages continue to rise, the opportunity cost for peasants to leave high school and enter the work force skyrockets. Good high schools can cost $3,000 for three years, and a high-school-age laborer can earn $150 a month; that’s a cost differential of about $8,400—a fortune for poor peasant families.

更重要的是,由于劳务薪资不断上涨,农民的替代性成本离开高中,进入劳务市场的越来越多。好的高中,3年需要花费3000美元,而高中的适龄劳务工作者每月可以赚150美元,这是一个近8400美元的成本差异---对一个贫困农民家庭来说,这是一笔财富。

Public health is another part of the problem that affects the poorer half of peasants, who make up about 28 percent of China’s college-eligible population. Scott Rozelle, codirector of the Rural Education Action Project at Stanford University, points to health problems, such as 40 percent anemia rates among poor and rural Chinese children—and the failure of the Ministry of Education to provide nutritious lunch programs. A spokesman for the ministry, asked about nutritious lunches, told NEWSWEEK to “get in touch directly with various schools in China, since China has so many schools and the conditions are different.”

公共健康是另一个难题,影响着占中国适龄上大学人口的28%农民.斯坦福大学农村教行动计划负责人斯科特·罗泽尔指出,健康问题,诸如40%的穷困的农村儿童贫血,并且教育部也没有提供营养午餐的计划。当教育部被问及营养午餐问题时,发言人告诉《新闻周刊》:“直接联络中国的各所学校,中国有如此众多的学校,每一所的条件都不同。”

A bureaucratic gap between the responsibilities of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education exACerbates the health problems of poor students. “There is not one school in a poor area that has a nurse, and there’s no budget for health exams,” says Rozelle. “We asked a thousand principals in poor schools the rate of anemia among their students, and 82 percent said, ‘What’s anemia?’ ” Anemia significantly drags down test results not only of students with the disease but also of their peers, because students with anemia tend to disrupt classroom learning.

卫生部和教育部之间互推责任加剧了贫困学生的健康问题。罗泽尔说:“贫困地区没有一所学校有护士,没有安排健康体检。我们询问了数千位贫困学校的校长学生的贫血率是多少,有82%的人问:‘什么是贫血’。”贫血不仅极大的影响着考试的结果,也让他们和同龄人相比,更易患病,因为贫血的学生往往会扰乱课堂学习。

An urbanite from Hebei province, Shi Shuo graduated from Tsinghua University in 2008 with a major in art design. “I think the number of peasant students definitely dropped in the four years I was there,” he says. “As resources become more and more concentrated into the hands of people with power and money, it’s more and more difficult for regular families to get into elite universities.” In the topsy-turvy Mao era, students carried their peasant background with pride, and elite universities were full of peasants. In a speech last year, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao mused about how when he attended university “almost 80 percent, or even higher, of my classmates were from peasant villages.” Yet as China’s economy started growing in the late 1970s, and wealth became more and more concentrated in urban areas, poverty and agriculture became symbols of an impoverished, out-of-touch China that many of its urbanites are happy to have moved beyond. “I live in a dorm, and all of my roommates are from urban backgrounds,” says Li Xiao, a rising junior at PKU. Li says that of all the kids she knows at school, just three or five admitted to having rural backgrounds; maybe more came from the country “but they’re ashamed to speak about it.”

施朔是一位来自河北省的城市人,2008年毕业于清华大学,主修艺术设计。他说:“我认为农民学生的人数肯定在我读书的那4年里有所下降。随着资源被越来越集中到权钱人物的手中,正常家庭越来越难以进入顶级大学。“这与毛泽东时代恰好颠倒了,同学们对农民身份感到自豪,顶级大学充斥着农民。在去年的演讲中,中国总理温家沉思着关于他大学时代“他的同学有80%甚至更高的来自于农村。”然而,而这70年代末期中国经济的飞跃发展,城市地区的财富变得更多,贫困和农业成了贫穷的象征,许多城市居民对外部的接触感到兴奋。正在北大上大二的李晓说道:“我住在宿舍里,我和我的室友都来自城市。”李晓表示,在学校的所有人,她只知道有3~5个来自农村,也许有更多来自农村的学生,‘但他们羞于提及’。

China’s education system, where peasants can get a rudimentary education before populating thousands of factories along its eastern coast, suited it when the country sought to be the world’s sweatshop. “At the same level of development in their history, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and the U.S. had practically full enrollments in high school,” says Rozelle. By contrast, only 60 percent to 70 percent of China’s current high-school-age students are in high school. Yet factory jobs will continue to migrate to places like India. Wages in China will continue to rise. And as long as China finds no better way to educate its rural poor, it’s staring down a future with a 100 million-strong underclass.

中国的教育体系里,农民可以得到基础教育,随后就去东部沿岸成千上万的工厂,适应尝试成为世界血汗工厂的国家。罗泽尔表示:“与中国发展程度相似的台湾、韩国、日本和美国的高中入学率为百分之百。”相比之下,中国目前只有60%~70%的适龄高中学生在读高中。工厂的工作将继续转移到印度等地。中国的薪资也将继续上涨。只要中国发现没有更好的方式来教育农村贫民,它就会在未来面临1亿之巨的下层社会。 |