|

|

本帖最后由 lilyma06 于 2011-11-28 10:51 编辑

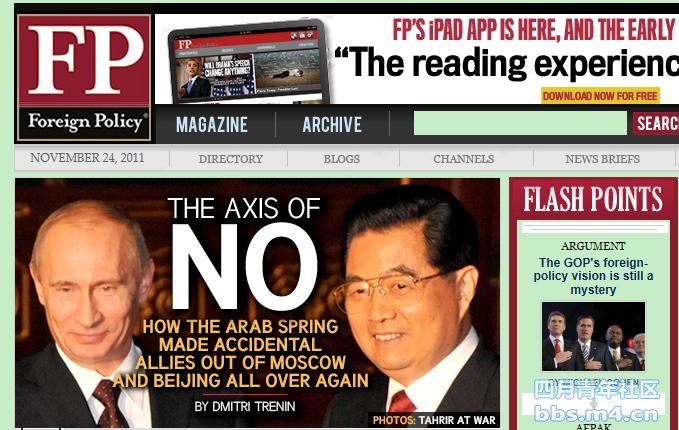

The Axis of No

How the Arab Spring made accidental allies out of Moscow and Beijing.

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/11/23/the_axis_of_no?page=0,1

Remember the Soviet-Sino split? Moscow and Beijing don't appear to. On the current developments in the Middle East and North Africa, at least, China and Russia have been increasingly coming together. At the U.N. Security Council, they either oppose Western initiatives or voice their reservations. To some, this looks like solidarity between two authoritarian governments; to others, a coordinated effort to dilute, and eventually dismantle, U.S. and Western domination of global politics. Although both these elements are involved, the reality is broader, and it needs to be better understood by Western publics and policymakers.

To begin with, there is no ideology involved. Although China still calls itself communist, it has long rejected the Maoist dogma, including in its foreign relations. Russia ditched communism exactly two decades ago. It is true that both countries are authoritarian, even if one is of a milder, and the other of a harsher variety. However, there is no such thing as an "authoritarian internationale" to inspire solidarity between the ruling autocracies. (Nor is there such a thing in the Middle East, if one looks at how Qatar has dealt with Muammar al-Qaddafi, or how Saudi Arabia is dealing with Bashar al-Assad). Both Russia and China are, above all, pragmatic.

There is also precious little regional geopolitical competition between them. China's global interests are essentially economic. It depends on Iran, for example, for a quarter of the oil it imports from the Middle East. Chinese companies are engaged in a number of projects throughout the region. The war in Libya left some 20,000 Chinese workers stranded. A similar number of Russian tourists were marooned in Egypt as Mubarak's regime fell. Moscow of course has vested interests beyond caring for its vacationers, as a supplier of arms or nuclear energy technology to several countries, but it is definitely not in a race with Washington for regional pre-eminence.

Nor does Beijing or Moscow feel any special affinity toward Middle Eastern rulers. Hosni Mubarak, after all, was a long-time U.S. ally, Tunisia's Zine el-Abidine Ben-Ali was close to Paris, and Qaddafi made peace with the West in 2003. Syria's Assad is different, of course: Damascus used to be Moscow's ally in the Cold War days, and it has kept friendly ties to Russia to this day. Syria's military has been equipped with Russian-made arms since the 1960s, and the Mediterranean port of Tartus is home to a facility used by the Russian Navy.

Certainly Russia does not wish to lose Syria. With Assad's fate hanging in the balance since March, the Moscow has opened lines to Syria's opposition. While hosting Assad's enemies in Moscow and deploring violence, the Russians have been urging Damascus to start political reforms, even as they have blocked formal condemnation by the Security Council of the Syrian government's crackdown. Beijing's approach has been essentially the same: demanding reform from Damascus, while talking to both the Syrian government and the opposition and refusing to support sanctions against Syria in Turtle Bay.

China's official stance proclaims Beijing's "support for the Syrian people." There is a huge difference, however, between this position and the attitudes taken by Western governments. For many in the West, such "support" means active involvement, not ruling out, in principle, the use of force. For the Chinese, it means allowing the Syrians to sort things out among themselves without outside interference and eventually recognizing the people's choice -- as Beijing has done, eventually, in Libya.

Like China, Russia rejects Western military interference in other countries' domestic affairs, whether in the name of humanity or democracy. But this is about much more than Beijing's or Moscow's concern for their own security. Libya has demonstrated to both powers that the West, acting essentially under pressure from domestic human rights constituencies (absent of course in Russia and China), can stumble into foreign civil wars even when its leaders should know better.

Libya, however, has always been a peripheral country strategically speaking. Not Syria. The Chinese and even the Russians -- who have better intelligence -- have no clue what will happen when the Assad regime falls. A full-scale civil war in Syria would make Libya pale in comparison. Such a conflict would be far more propitious for sectarian strife and religious radicalism, the Russians and the Chinese argue, than for democracy and the rule of law.

Syria's position in the heart of the region also means that a full-blown domestic conflict there can affect its neighbors -- above all, Lebanon and Israel -- and bring into play such regional actors as Hezbollah and Hamas. The Russians, concerned about Islamist extremism in the North Caucasus and Central Asia, and the Chinese, who import most of their oil from the Middle East, can hardly welcome Syria's meltdown.

In principle, applying pressure on Damascus while simultaneously facilitating an intra-Syrian dialogue should help prevent this worst-case scenario. In reality, however, Moscow and Beijing must have concluded that the West has written Assad off, and is in fact preparing for regime change. Seen from this perspective, sanctions are a step in the escalation game that would have to be followed up by more forceful measures -- as Libya has just demonstrated.

China and Russia's policies on Syria differ from the United States' and Europe's for two basic reasons. One, Moscow and Beijing do not believe that becoming actively involved in other people's civil conflicts is wise or useful. Two, they have no pressing interest in the elimination of the Assad regime as part of an anti-Iranian strategy. In any case, the Chinese and the Russians don't see much of a strategy at all; they think that, surprised early this year by the Arab revolt, the Americans and their allies are now being guided more by short-term politics than by long-term strategic calculus.

All or part of these concerns may be valid. Yet Moscow and Beijing have to admit that critique is not the same as leadership, which Russia covets, and which China cannot forever escape from. Modern international leadership calls for coming up with realistic alternatives, reaching out to others, and building consensus. Saying no is not enough.

|

评分

-

1

查看全部评分

-

|