|

|

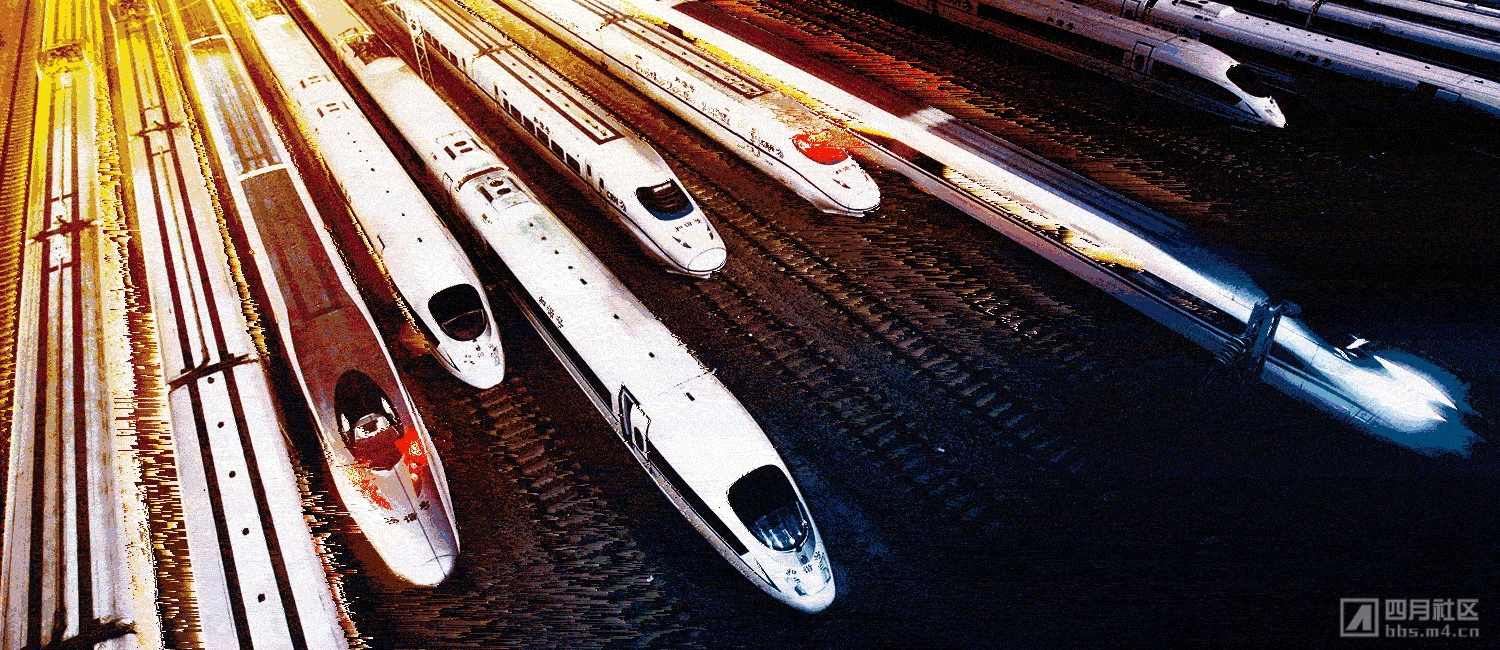

【中文标题】高速帝国

【原文标题】High-Speed Empire

【登载媒体】外交政策

【原文作者】Tom Zoellner

【原文链接】http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/03/13/high_speed_empire_chinese_trains

中国的铁路覆盖越来越广、设施越来越现代化、技术含量越来越高,但同时它也越来越复杂、问题层出不穷,并且出现了危险的信号。想来尝试一下吗?

子弹头列车向中国北部工业城市太原疾驶,似乎眨眼之间,笼罩在雾霾中现代化的北京城市景观就变成了开阔的田野。苏大卫在餐车大嚼开心果,他小心地避免碎屑沾在蓝色的围巾上。他正在前往320英里外的一座城市,与一家私募股权公司约好在一早开会。他的身后是一片模糊的中国乡村景象,农田和工厂以惊人的186英里的时速倒退,旁边高速公路上的汽车就像是在爬行。

苏在全球资本投资集团的工作需要频繁出差,他喜欢利用新型的高速铁路旅行。中国政府在十年里以闪电般的速度建造了几十条高速铁路,目前总价值为5000亿美元。

在利用空气动力悬浮而稍有晃动的车厢中,他说:“几年之内肯定无法收回成本,但是10到20年之后呢?这绝对是超值的投资,我是说,你看,人都坐满了。”他放下开心果的袋子,向车厢里指了指。昏昏欲睡的的旅客藏在报纸后面,年轻的嬉皮士戴着耳机打盹,几个警察在大声地打着纸牌——一片常规的工作日通勤景象,背景是窗外灰色、模糊的景象。

中国令人瞠目结舌的高速铁路事业在2007年正式启动,它的成就经常被当作一个坚定不移的国家走向繁荣的经典案例来研究。《纽约时报》专栏作家Thomas Friedman曾经羡慕地称其为强大技术信心的“登月奢望”,能与其相提并论的还有中国在航天、生物科学和电动汽车领域的前沿工作。高速列车每天从超级现代化的车站开出几十班,车站里有室内花园和镜子一般的地面。车头被设计成子弹的形状,车厢外观像天鹅一样的优雅和光亮。年轻的乘务员身穿津芬德尔色的制服和贝雷帽,为乘客提供啤酒和咖啡。

高速列车从北京开到上海——大约相当于从纽约到芝加哥的距离——的时间还不到5个小时,总共超过6000英里的特制铁道把这两个城市与其它大城市连接起来。时长8个小时的北京到广州的高速铁路是世界上最长的子弹头列车线,在未来15年里,中国所有人口超过50万的城市都将开通高速铁路。

缩减通勤时间等于扩大员工的居住范围,并且就像所有铁路的效应一样,带动沿线地价的上升。尽管有部分线路人员的上座率不高,但总体经营效果是非常不错的。大约130万人——中国所有铁路乘客的四分之一——每天都会乘坐高铁。由于业务流失,航空公司不得不削减航线。

但是,短期内的快速发展必然出现了一些危险动作,数千英里的铁道或许达不到国际标准。导致40名乘客死亡的事故揭露了大规模、根深蒂固的腐败现象,涉及金额数百万美元。资产高达5亿美元的企业在2011年的资金链出现问题,负责这个项目的部委无力偿还债务,逼得北京不得不出面干预。承包了大约一半高铁工程的国有建筑集团在2013年秋天也出现了类似的资不抵债的问题,1月份,公司的总裁“意外”从上海的一所公寓中坠亡。

加速铁路建设的决定,是北京通过大规模的基础设施建设来推动气喘吁吁的经济的重要举措之一,目标是让中国在2020年成为“中等繁荣的社会”。但是今天,铁道凸显了财政的问题,暴露了中国整体经济策略中范围广、深层次的缺陷。

这一切都是在提醒,那些把中国的高铁帝国当作基础设施建设样板的人应当看到更深层次的问题,那些用羡慕的眼光看着穿梭在中土帝国的光鲜亮丽的车厢的人,在加工出自己的第一批零件之前要好好想一想。

高速铁路或许是当今世界的新玩意,但它其实是在几十年前由一名日本的工程师岛秀雄发明的。他在1957年展示了一个轻型车厢,通过给每个轮子直接传输电力,使其以不可思议的速度运行。电力可以通过高架电线和导电弓传输给列车,就类似与街上的有轨电车,只不过整个设备必须沿轨道精密地设置,不可以有交叉和急弯。

岛秀雄的创新吸引了日本国有铁道总裁、吝啬的职业官僚十河信二的关注,他认为目前街道上塞满了美国和日本的汽车,高速铁路是挽救他所深爱的、即将沦陷的铁路事业的良方。十河的绰号是“大嗓门老家伙”,因为他喜欢大喊大叫。他有意低报东京到大阪的高速铁路造价,在手中仅有一半资金的情况下,想方设法推动政府批准建造“新干线”。以飞机机身为模型的光滑、优雅的车厢在1964年东吉夏季奥运会期间首次启用,立即成为日本战后的骄傲和技术能力象征。(法国也利用同样的平台开发了自己的高速列车TGV。)

在90年代末,中国铁道部迫切希望增加铁路的客运能力,于是开始逐步淘汰老旧的短途客运列车,提升长途列车速度——这被称为“提速”运动。列车最高时速从30英里上升到100英里,整个体系的运力大幅提升,乘客的平均旅行距离增加了一倍多。铁道部在华北率先开始测试高速铁路京沪线,2004年,他们把一大批合同交给法国、德国和日本公司。

帝国的建造

高速铁路逐年的变化。

铁道部(神秘的政府机构,绰号“铁老大”)向阿尔斯通、西门子和川崎等生产商购买了整套列车,包括制动系统、牵引转换器、控制网络等技术,中国人在自己的工厂中将其组装起来。中国制造的尖鼻子子弹头列车,配上白色喷漆和黑色的粗体字“CRH0”——中国高速铁路——看起来的确与众不同。但其实有些是西门子的Velaro(这款高速列车在2006年创下时速250英里的纪录)、有些是阿尔斯通的新潘多利诺(理查德•布兰森在英国最中意的维珍火车),还有些是加拿大庞巴迪公司的Zefiro250,配有480张床位。今天中国运行的几乎所有高速列车都用国产配件改装过,前提是在国家专利制度允许范围之内。

这个过程被政府委婉地称为“吸收和再创新”,它展示了中国改进外国技术的天份,这原本是日本人最擅长的手段,它不但利用这种方法创立了本土的产业,还开始向外出口整车和零部件。对于一个直到90年代末还在使用燃煤蒸汽机车的国家来说,快速吸纳高速铁路的进步的确值得称道。但这依然不足以支持截止到2003年每年增长10%的经济规模,它仍然需要更快速的基础设施,来与那些冒着青烟的工厂和雨后春笋般出现的新城市相配套。

2008年,美国的金融危机让世界经济形式恶化,但这却是送给中国铁路的一份大礼。如果你梦想有更多的低技能就业机会、大额的承包合同、持续的经济增长模式,除了高速铁路之外别无他选。这项产业为社会经济学领域的几乎所有岗位都提供了就业机会——从高级管理层、有大学教育背景的工程师到销售人员、乘务员、工厂技术人员和力工。

2008年11月9日是铁路历史上重要的一刻,中央政府宣布了一项巨额国家经济刺激方案。第二年,刺激计划中一大笔资金被用来改善公共基础设施,在一年时间里,铁路的投资额从490亿美元飙升到880亿美元。原始计划是在未来三年里开通42条高铁,自从沙皇亚历山大三世修建横跨西伯利亚的铁路之后,再也没有哪个国家的中央政府出台过如此庞大的铁路建造计划。

了解中国历史的人都会明白北京拥抱高速铁路背后的讽刺含义。英国公司在18世纪中期的鸦片战争期间用军舰敲开了中国的大门,他们敦促不情愿的主人修建铁路。清政府起初抵制“火车”,担心这会带来大量廉价的进口商品,但最终还是退步,允许外国承包商修建了几条铁道。中国的军事专家也发现,在铁路的帮助下,“一名士兵的影响力无比巨大”,而且铁路可以在英国人再次入侵时作为抵抗的工具。

然而最后,为修建第一条铁路的短期借贷让中国政府付出了代价。国家债务达到了崩溃的边缘,由于政府无力偿还贷款,外国银行欣然接手了作为抵押物的铁路资产。整个系统在世纪之交开始由外国人掌控,在中国人已经痛苦不堪的所谓西方列强手中的“屈辱世纪”中,又添加了浓墨重彩的一笔。

民众的怒气催生了义和团运动——开始于1899年针对基督教徒和外国人的暴力袭击运动,但是被外国军队击败之后,在法国、德国、英国和美国联手为此索赔的时候,民众的怒气再一次被激发。清朝已经脆弱不堪,1911年,全国各地爆发抗议活动。导火索之一就是把四川汉口铁路收归国有的决定,这家企业由私人出资在湖北省内运作。失去了积蓄的数千名愤怒的抗议者在四川集结,军队向人群开枪,打死了数十人。反清组织称其为“护路运动”,清政府的镇压行动最终失败,政府愈加颜面无存,公众迫切期望出现一个崭新的政府。

第二年,在中国无数家族手中存在了2000余年的帝王制度覆灭了。帝制经历了瘟疫、入侵、饥荒、内战和干旱,但最终倒在铁路的脚下。

一百年之后,一条崭新的铁路铺设在同样的省份中,但再次让中国政府陷入窘境。

在长江三角洲流域,3月并不是最潮湿的季节,但是2012年的3月春雷响彻大地。雨水浇灌在新建成的武汉至宜昌高铁线上,缓慢地侵蚀架设在湖北农田上铁轨的地基,导致铁轨下沉9个毫米,最终坍塌。整个区段需要重新替换。这条铁路被暂停实用,数百名工人连夜工作以减小损失,他们用重型设备铺设新的铁轨。湖北建筑总局的局长在接受《华尔街日报》采访时说,责任并不是雨水,“如果雨水能摧毁一条铁路,那说明这个项目的质量是什么样的?”这其中不无嘲讽的意味。

这是一个恰逢其时的问题。一个星期之前,中国媒体报道项目的负责人并没有按指令使用碎石构筑铁轨地基,而是用普通的泥土,因为其价格低廉,差价被私吞。共产党的喉舌媒体《环球时报》在采访了一名铁道部内部人士之后,报道说这种偷梁换柱的行为多年来极为普遍,“贪污的石头可以盖一所大房子”。实际上,这次坍塌事故说明数千英里的铁道都存在严重的缺陷,不仅仅是泥土,还有混凝土的问题。

混凝土是中国铁路帝国的必要条件,因为大部分轨道都被巨大、灰色的柱子高架在农田、河流、土路和一切障碍物之上。例如,从北京到上海的819英里高铁线上,80%的路段都在高架桥上,下面的支撑物是光秃秃的柱子,厚15英尺,高度随地表起伏不定。柱子的成份应当是细沙、水泥和一种叫做“粉煤灰”的混合物,后者可以从中国的燃煤电厂烟囱中收集到。

在2008年铁路建设高峰期,中国铁道第一勘察设计院估算,当时的高质粉煤灰产量每年可供建设100公里的高速铁路。但是中国飞速的工程进度远远超过了这个数字,实际上,对粉煤灰的需求已经超过了世界所有煤电厂的产量总和。于是,一些建筑公司私自更改了配方以满足工程进度,他们购买低质的粉煤灰,动用与政府的关系来规避正常的质控程序。

所以,中国总长6000英里的铁路都是脆弱、易损的。西南交通大学的朱明在2011年接受《南华早报》的采访时说,如果中国继续使用低质量的粉煤灰,“审判日”将在铁轨铺设5年之内降临。铁路基础设施的诚信问题不仅仅是“造成列车延误几个小时的偶发性小裂缝”,而是“让整条路线瘫痪几天、几周的大问题”。

朱说:“如果发生这样的问题,中国高铁的奇迹将一钱不值。”(交通运输部、国家铁路局和中国铁路运输总公司没有回应《外交政策》采访的要求。)

在中国的高铁建设热潮中,工程进度似乎比质量更重要。Jan Moorlag是武汉到广州段高铁一家建设承包商的项目经理,他回忆起自己负责的一段铁路计划在2009年12月竣工。但是,在打通一段6英里长的隧道时,项目进展落后于既定进度。于是一家当地承包商找到他的中国老板,说应该把进度落后的事情告诉铁道部。Moorlag说:“我觉得这个人宁可上吊也不愿意在铁道部面前丢脸。他整个晚上都在打电话,第二天早晨,工地上一下子出现了500名工人。”一个星期之后,一切都按时竣工。“总之,项目永远不会推迟。”

中国的铁路建设特殊之处就是快速和原始的奇怪组合。短时间内集结起来的工人就像一个工兵旅,他们没有基本的机械设备,比如推土机。Moorlag说:“工作现场没有足够的机械设备,但是他们有人,廉价的劳动力。”他吃惊地看到如此庞大的人力出现在如此大规模的建设工地,于是拍摄了很多照片,我们看到工人用手拖拽石板,用手推车倾倒混凝土。

这种匆忙的状态不仅降低的建筑质量,还让工人在铲起第一方土之前所需要的分析流于形式。一位不愿透露姓名的铁路工程师在2011年对《人民日报》的编辑杜军晓说:“我们实在无法保证工程的质量。在有些项目中,调查、设计和施工是同时进行的,甚至有些项目根本就没有这三个步骤。”

另外一位工程师告诉杜,他自己绝对不会乘坐高铁,因为担心生命安全。杜谴责道:“那些参与建设的人都不敢乘坐高铁,这里面一定存在严重的问题。”

的确如此。2011年7月23日,一辆列车在温州附近进入了“盲区”——就是一段没有被信号覆盖区域,与另一辆停在铁轨上的列车尾部相撞。

2011年7月25日,一辆子弹头列车下是两天前在中国东部省份浙江双屿镇相撞的两辆高铁列车残骸。

相撞造成三节高铁车厢从65英尺高的高架桥上坠落,40人死亡。官方的第一反应是毛式的掩盖,中国所有媒体都被要求尽量简短地报道这件事,中国宣传部在一份文件中要求“不要提问题,不要详述事件”。一节变形的车厢被当场掩埋(官方说是为救援清理障碍),律师们被警告不要提起责任诉讼。

时任总理的温家宝承诺要彻查问题原因。2011年12月,政府发布了一份罕见的、直截了当的报告,结论是“灾难性事故的原因是列车控制系统设计的严重缺陷、当局所采取的草率的安全措施和系统应急响应计划的缺乏”。一个信号系统在遭到电击后失灵,尽管这类设备一般会有备用系统,但报告认为急功近利的铁路建设或许导致偷工减料的行为。

政府在事故调查之后开除了54名铁道部员工,但大头头在此之前已经被捕。事故发生的5个月之前,大规模铁路扩建的策划人、铁道部部长刘志军因滥用职权和腐败被捕,据称贪污金额高达1000万美元。《纽约客》编辑Evan Osnos曾详细报道铁道部内部新闻,据他描述,刘的野心是“用钱铺平进入党中央的道路,直达政治局。”

接踵而来的丑闻揭露刘在多年前就利用职权为他的弟弟刘志祥谋取职位,但后者也同样滥用职权。刘志祥的武汉铁路局副局长职务在2006年戛然而止,他以腐败、盗用公款和谋杀的罪名被判处私刑,后来减刑到16年。他雇凶刺死一名试图举报他的承包商。(Osnos报道:“据一名法律人士透露,这位承包商在遗嘱中预言了他的命运:‘我若遇害,就是贪官刘志祥指使人干的。’”)

2013年7月,刘志军被判处死缓。对他的歌功颂德在高铁的官方历史中被抹去,但是铁路建设和财政的严重缺陷永远无法掩盖。政府后来发现仅在北京到上海的高铁建设中,有2800万美元被贪污。

中央政府试图向全世界展示严惩腐败的决心。2013年3月,铁道部被解散,划入交通运输部,其原职能并不包括管理铁路运输,这个机构负责监管铁路安全和制度。国家铁路局目前负责审查,原铁道部下属的中国铁路总公司负责国家铁路系统的建设。但是有些问题没有改变。中国铁路总公司依然与其主要的承包商保持合作——中铁集团和中国铁路建设总公司,它们都是国有企业,在福布斯上排名世界前列。

支持中国高铁的人可能会指出,一个复杂的全国铁路网,每天运送130万乘客,7年时间里只出现了几十人死亡的事件,算是相当安全了,至少比全球航空产业要安全。但是,为了完成生产计划而偷工减料的行为在工厂里非常普遍,中国的工业死亡人数在全世界最高。人命成本是北京高速GDP增长中无法抹去的烙印。

快速的发展还带来了财政危机。中国在基础设施项目上的原则是“花钱来挣钱”,但是用铁路来举例,如果最终挣不到钱,将会入不敷出。摩根士丹利新兴市场负责人Ruchir Sharma在接受《外交政策》采访时说:“他们建造高铁的目的是实际需求还是为了推动GDP?如果一个国家依靠债务来获取增长,必将陷入危机。”

它的确是在依靠债务。2008年,在中国宣布了5860亿美元的国家经济刺激方案之后,1460亿美元进入了铁路系统。很明显,中央政府不想直接投资,而是暗示银行,说占据刺激方案将近四分之三的基础设施项目将会得到批准。贷方一下子多起来,利率随之降低,中国银行资助了建设的热潮。

信用问题基本上是家庭内部事务,因为中国的“四大”银行——建设银行、中国银行、工商银行和农业银行——都是国有企业,他们吸纳成千上万的小额存款,向国家和地方资本项目发放大额贷款。对中央政府来说,高铁的冒进是否可以带来足够的收入以偿还贷款,不是一个重要的问题。但是这意味着,银行手中将会有一大批不良贷款——都是铁路项目带来的。

中国与世界上其它大国不同,它没有足够的优势来忽略自由市场的规律,在地图上随心所欲地施划铁道线。世界银行在2009年指出了这一问题:“铁路建设的资金来源是主要的问题,部分原因在于,很多铁道建设项目都是以达成地方经济发展指标为目的,而不具备商业可行性,并且忽略了广大的经济和社会效益。”

世界上最长的子弹头高铁线路,从北京到广州,至今没有找到合适的市场定位。8小时的高铁与3小时的飞机相比没有优势,甚至国有媒体《北京新闻》都在说,票价小小的差别不足以弥补时间的损失。在中国高铁漂亮、丝滑的外壳下,经济性到目前为止依然黯淡无光。

事情在2011年终于难以为继,铁道部透支了所有资金和信用,无力偿还贷款、支付承包商欠款,拖欠金额高达数亿美元。尽管铁道部是中央政府的臂膀,但它也有责任为项目偿还贷款。铁路建设的巨轮终于停止了,在中央政府出面支付部分欠款和延续了信用之后,情况暂时得以稳定。

2013年改组铁道部本应让铁路产业有良性发展的机会。但事实并非如此,同样的为题再次出现。去年,中铁集团无法偿还债务、无力支付数千名工人的工资。2013年10月,公司的资产负债比为85%,说明财务存在严重危机。未来的前景一片灰暗,直到自身也举步维艰的中国铁路建设总公司设法掏出数亿美元偿还了它亏欠建筑公司的钱。似乎更让中国雪上加霜的是,中铁集团总裁白中仁从他4楼公寓的窗户中坠亡,公司声称是意外时间,但媒体认为是自杀。消息传出后,国有企业的股票下跌了4个百分点。

一些中国学术界人士公开批评高铁项目,说其毫无用处,而且必将带来债务危机。北京交通大学运输经济学教授赵健,在他位于一栋毛式建筑物的顶层办公室里,几乎是咆哮着说:“中国承担不起这样的事!就好像是一部耗资3亿美元却没有观众的好莱坞电影。”

问题并不完全是中国铁路建设总公司拖欠多少资金,而是在于,高铁所面临的问题是否仅仅是对并不需要的基础设施投资过剩的表象。这种无以为继的做法所面临的风险之所以尚未表露出来,是因为债务并未体现在中国的资产负债表上,而是体现在国有银行和地方政府的账簿上。据标准普尔提供的信息,到2013年底,中国公司积累了超过12万亿的债务,这些债务中有多少无力偿还?有多少需要中央政府出面偿还?

北京已经开始收紧贷款,并且对银行业进行市场化改革,很多分析人士认为政府控制未来债务危机的能力还是足够强大的。布兰德斯大学的国际金融教授Peter Petri说:“隐藏在后面的是有4万亿现金储备的经济体。”换句话说,中国还没有达到类似次级抵押贷款危机的程度。

但是有些分析人士依然表示担忧,他们提到了中国极速增长的债务与GDP比例。里昂证券亚洲的经济师历来看好中国,但是在2013年5月却发表了一份充满担忧的报告,说“中国已经陷入用债务换增长的误区”,这个国家必须进行全面的经济诊疗,以确保投资得到有效的控制。高速发展的梦魇或许还将持续多年。

诚然,铁路带来的好处并不完全能通过资产负债表体现出来。官方对支持高铁的主要论点是它提升了短期的就业率——10年中出现了250万临时就业岗位——而且还留下了一项可长期使用的资产。更快地抵达广州周边星罗棋布的工厂,意味着装满商品的集装箱可以更快地抵达贸易港口。淘汰缓慢的老式铁路列车,让它们可以承接货物运输,这带来了真金白银的收入。在生产领域,一天的优势可以转化成数百万美元。在改良了铁路运输服务之后,中国现在的运输量是90年代的三倍,也就是说中国可以在远离城市的地区开采煤层,正如清政府曾经期望的那样。高铁可以让每天通勤的人走得更远、更快,这也提升了劳动力的流动性和经济机会。

2012年12月26日,中国旅客携带行李走出北京西站。

然而我们不确定普通工人是否真的可以享受这样的机会。国内最常见对中国高铁的抱怨是,它是为富人修建的,也就是那些像全球资本投资集团的苏大卫那样的高收入商人群体,牺牲的是这个国家已经运作了超过100年的传统、可靠的铁路网。北京出现了一句俏皮话“被高速”,意思是说“你不得不乘坐高速铁路”,基本上等于“你完蛋了!”

高铁所面临的一项大考是在春节期间中国的民工迁徙活动,工厂里的工人在这个时候要回到他们的家乡与家人团聚。过去40年里,中国约有2.58亿人次搭乘铁路运输出行。但是在2013年,只有很少人购买了子弹头列车票,因为它的价格相当于平均100美元月薪的四分之三。一家医院的看门人梁秀霞在接受《中国日报》采访时解释了她为什么宁愿花15个小时乘坐普通铁路或者长途汽车,她说:“省时间对我不重要,省钱才重要,我觉得所有农民工最关心的都是钱。”

有一些迹象显示中国的铁路正在逐渐民主化,虽然是被迫使然。温州事故之后,官方不但把京沪高铁的最高时速从236英里降到186英里,还推出了廉价车票。2011年,中国铁路副总经理胡亚东说,“人民的满意度”将成为“衡量铁路工作质量的基本标准”。

尽管问题多多,但中国的高铁依然震动了整个世界,在某种程度上也震动了美国。

到目前为止,美国的高铁历程基本上就是昂贵和失望的过程。美铁在波士顿到华盛顿之间的所谓Acela项目上投入了6.61亿美元,但是列车难看的设计和共享磁道技术让它勉强达到75英里的时速。于是,巴拉克•奥巴马总统在2009年承诺,任何州如果有能力在两个城市之间修建时速180英里的高铁,将获得80亿美元的配备基金。过去两年里,共和党州长否决了俄亥俄、佛罗里达和威斯康星州的高铁项目,只剩下加利福尼亚成为最大的联邦基金受益者。即使在那里,有关环境和成本的诉讼一直在阻挠项目的进展,但是州长Jerry Brown始终给予强力的支持。他在2013年4月乘坐上海到北京的高铁,之后接受记者采访时颇为羡慕地说:“这里的人们在脚踏实地地做事情,他们不是游手好闲地高谈阔论,整个世界都在以马赫速度前进。”

加利福尼亚对中国的兴趣得到了一些回报。坐在Brown这趟列车上的另外一位乘客是蒋雷,唐山机车有限公司的设计工程师。他在接受《洛杉矶时报》的采访时说:“我们对加利福尼亚很感兴趣,而且有信心让中国的技术在美国获得成功。”生产商已经开始筹划成立一些合资公司,类似于那种最早把牵引机车引入中国的机构。加利福尼亚高速铁路管理局说他们会尝试与国有资金管理机构合作,比如中国投资有限公司,据说双方已经开始谈判。其目的是为洛杉矶到旧金山高铁所需的680美元融资。即使考虑到其带来的经济效益,这也将在两个大陆之间造成巨额的铁路债务。

与此同时,摩洛哥正在计划在马拉喀什和丹吉尔之间铺设350英里的高铁。到2015年底,沙特阿拉伯期望哈拉曼高速铁路的首次运行可以满足期望,这条线路的目的是把朝圣客从吉达送往麦加。这趟一个小时的路程将缩短为30分钟。越南官方近期在计划把从前敌对的两座大城市,河内和胡志明市用720英里长的高速铁路连接起来。

中国再高兴不过提供帮助了。来自北京和上海的那些有足够经验、跃跃欲试的公司纷纷在肯尼亚、以色列、哥伦比亚、委内瑞拉、土耳其和俄罗斯参与投标,因为中央政府给出的官方销售策略是“走出去”。在缅甸,一家中国公司已经与当地政府合作,建造车厢生产车间。中国现在是这个产业中毫无争议的世界领袖,或者可以用中国工程院接受爱国主义色彩浓重的《环球时报》采访时的态度来描述:“高铁之于中国,就是腕表之于瑞士、电器之于日本和机械之于德国。”

北京的地缘政治野心也因此而渐渐膨胀。2013年,老挝政府批准一家中国公司在其境内开建一条钻山铁路,到2019年连接云南省和新加坡。政府还在考虑用铁路把德国连入亚洲的“新丝绸之路”,利用深入亚洲国家的铁道线,中国在营造一个全新的经济样板。这必将起到决定性的作用,因为高铁并不是为了运送货物,而是更重要的东西——人。

中国可以利用高速铁路排挤调周边国家的小企业,让自己的流动商人涌入这些区域。这种草根式的经济和文化影响力很快会转化为政治影响力。用铺天盖地的铁路网改造东南亚,会给中国巨大的优势来左右当地的贸易政策。在军事上,子弹头列车被Nathan Bedford Forrest之后的每一个军事将领都理解为“不惜代价抢占先机”。高铁将让中国成为亚洲遥遥领先的超级势力。

当然,所有这一切都是建立在铁道帝国可以找到更好的方法来加固其结构和经济根基的假设之上。中国以异乎寻常的勇气用这种方式把它的大城市连接在一起,现在,它必须要想办法证明这种方式是有成效的。

原文:

Chinese rail is sprawling, modern, and elegant. It's also convoluted, corroding, and financially alarming. Wanna take a ride?

The bullet train hurtles toward the industrial city of Taiyuan in northern China, and seemingly within seconds, the modern, smog-soaked Beijing skyline gives way to open fields. David Su is munching on pistachios in the bar car, careful that not a crumb hits his blue foulard scarf, as he heads some 320 miles to reach his early-morning appointment for a private equity firm. Over his shoulder, the Chinese countryside is a disembodied blur: farms and factories receding at the mind-aching speed of 186 miles per hour. Cars on a nearby highway seem to be creeping along by comparison.

Su travels frequently for his job at Global Capital Investments Group, and he likes this new high-speed train, zipping along on one of several dozen lines built by the Chinese government in a decade-long blitzkrieg program that now has a price tag of $500 billion.

“This will take a financial loss for a few years,” he says, as the aerodynamic carriage rocks and sways. “But 10 to 20 years from now? This will turn out to be a great investment. I mean, look at it now. It’s full!” He puts down his bag of pistachios to gesture to the car, where drowsy travelers are hidden behind newspapers, young hipsters are nodding along with their earbuds, and a group of policemen are playing a voluble game of cards: a workaday commuter scene in front of a hallucinogenic smear of color outside the windows.

China’s extraordinary high-speed train enterprise, officially launched in 2007, has often been held up as a grand case study for how a determined nation can build its way to prosperity. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has admiringly termed it a “moon shot”1 of technological confidence, of a piece with China’s front-line work in aviation, biosciences, and electric cars. Trains make dozens of departures a day from supermodern stations with indoor gardens and mirror-like floors; the lead cars are needle-nosed, their trailing bodies majestic and sleek as swans; and young attendants in zinfandel-colored uniforms and berets serve wine, beer, and coffee.

The trains eat up the journey from Beijing to Shanghai -- roughly the same distance as that between New York and Chicago -- in slightly less than five hours.The trains eat up the journey from Beijing to Shanghai -- roughly the same distance as that between New York and Chicago -- in slightly less than five hours. More than 6,000 miles of dedicated track connect these and other major cities, and the eight-hour run between Beijing and Guangzhou is the longest bullet-train line in the world. A majority of Chinese cities with populations over a half-million are supposed to be connected within the next 15 years.

Shrinking commute times are expanding the horizons of where employees can live and, as railroads always do, are boosting the value of land near train stations. Although some lines have struggled to find their customers, total ridership has been relatively healthy thus far: about 1.3 million people -- roughly a quarter of Chinese rail users -- climb aboard each day. Airlines have had to cut routes because of lost business.

But building so much in such a short period has necessitated dangerous shortcuts. Thousands of miles of track may not be up to international design standards. Forty passengers died in an accident that revealed a culture of deep-set and spectacular corruption, involving the embezzlement of millions of dollars. And the half-trillion-dollar enterprise rests on financing so shaky that work ground to a crawl in 2011, when the ministry responsible for the project couldn’t service its debt or pay hundreds of millions of dollars in bills -- requiring Beijing’s direct intervention. The state-owned group building roughly half of the rail encountered the very same problem in the fall of 2013, when it ran out of cash. In January, the company’s president “accidentally” fell to his death from the window of his Shanghai apartment.

The decision to radically accelerate rail is one manifestation of Beijing’s effort to push breathless economic growth through massive infrastructure projects. The goal has been to make China a “moderately prosperous society” by 2020. But, today, the rail project’s underlying financial dysfunction is representative of much broader and deeper flaws in China’s overall economic strategy.

All this is to say that those who consider China’s empire of rail a model of infrastructure development ought to take a more critical look -- and that countries gazing with understandable envy at the sleek marvels crisscrossing the Middle Kingdom should measure twice before they cut their first piece of rail.

igh-speed rail may be a contemporary obsession, but it was invented decades ago by a Japanese engineer named Hideo Shima, who demonstrated in 1957 that a lightweight carriage could be made to travel at game-changing speeds by feeding power through a motor straight to each wheel. Electricity could be channeled to the train through a set of overhead wires and a pantograph -- a method similar to that used for years by city streetcars -- except that the whole apparatus had to be on a dedicated track kept free of road crossings and sharp curves.

Shima’s breakthrough attracted the attention of the head of Japanese National Railways, a curmudgeonly career bureaucrat named Shinji Sogo, who thought it was the right tool to save his beloved railway from obscurity at a time when automobiles were all the rage in the United States and Japan. Sogo -- nicknamed “Old Man Thunder” for his yelling -- deliberately fudged the estimated price tag of an inaugural link from Tokyo to Osaka. Acknowledging only half the cost of the project, he blustered his way through red tape to win approval for the Shinkansen, or “main truck line.” The sleek and graceful train, designed to look like an airplane’s fuselage, debuted in time for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo and became a symbol of postwar Japanese pride and know-how. (France would develop its high-speed rail, TGV, from the same platform.)

In late-1990s China, the Ministry of Railways was eager to make room on its lines for an increasing number of freight cars, so it began phasing out sluggish passenger trains on short routes and hustling its long-distance trains -- a campaign dubbed “Speed Up.” The maximum locomotive speed was bumped from 30 to 100 miles per hour. The system’s total capacity opened up, and the distance traveled by an average passenger more than doubled. The ministry laid a pilot set of high-speed tracks in northern China, began planning the Beijing-Shanghai link, and in 2004 awarded a series of contracts to companies from France, Germany, and Japan.

Building an Empire

High-speed rail construction by year

The Ministry of Railways (a secretive bureaucracy nicknamed “Boss Rail”) purchased complete train sets from manufacturers like Alstom, Siemens, and Kawasaki -- as well as the technology for brake systems, traction converters, and control networks, which the Chinese then assembled in their own factories. China’s needle-nosed bullet trains can look quite distinctive with their white livery paint and “CRH0” -- China Railway High-Speed -- in thick black block letters. But some are the Siemens Velaro model (a version of which set a 2006 world speed record at 250 mph); others are Alstom New Pendolinos (the favorite of Richard Branson’s Virgin Trains in Britain); still others are the Zefiro 250 type, made by the Canadian company Bombardier and equipped with 480 beds. Nearly all high-speed train models that China uses today have been refitted with new domestic-made parts, reverse-engineered once the patented machinery was safely within the country.

This process, which the government euphemistically calls “digestion and re-innovation,” demonstrates China’s genius for improving foreign technology, a skill once dominated by the Japanese, and it set the course for a home-built industry that would soon be able to export its own train sets and parts. For a country that was still manufacturing and using coal-fired steam trains as recently as the late 1990s,2 the rapid absorption of high-speed rail marked noteworthy progress. But it wasn’t enough to support an economy that, by 2003, was growing 10 percent annually and needed faster infrastructure to support its smoke-spewing factories and instant cities.

In 2008, the U.S. financial crisis soured the world economy, but the downturn was a great gift for Chinese rail. If you were trying to dream up a tool for creating low-skilled employment, generating big construction contracts, and laying the foundations for continuing industrial prowess, you would have a hard time doing better than high-speed rail. If you were trying to dream up a tool for creating low-skilled employment, generating big construction contracts, and laying the foundations for continuing industrial prowess, you would have a hard time doing better than high-speed rail. There are jobs for everyone on the socioeconomic spectrum -- from top managers, to university-trained engineers, to sales agents, to running crews, to factory foremen, to shovel gangs.

On Nov. 9, 2008 -- a hinge moment in railroad history -- the central government announced a giant national stimulus package, and the following year it revealed that the largest chunk of money would go to improve public infrastructure. Investment in rail projects soared from $49 billion to $88 billion within the space of a year. And the original plan was to open 42 high-speed lines within the next three years. Not since Czar Alexander III built the Trans-Siberian Railway had a central authority taken on such an ambitious rail project.

The irony of Beijing’s embrace of high-speed trains is clear to those who know the country’s history. After British companies pried their way into China with gunboats during the Opium Wars in the mid-1800s, they urged their reluctant hosts to build railways. Initially resistant to the “fire cart” and fearing an influx of cheap imported goods, the Qing dynasty -- with an eye toward opening up coal mines in the country’s interior -- eventually capitulated and allowed foreign contractors to build several lines. Chinese army strategists also realized that, with the help of a railway, “one soldier can have the impact of a dozen” -- and that rail could be used to fight the British if they ever invaded again.

In the end, however, the real threat to the Chinese government came from all the short-term borrowing it engaged in to build the first lines. The national debt metastasized to crushing levels, and with the government unable to keep up with loan payments, foreign banks were only too happy to foreclose on the railway’s assets. The entire system was under foreign control by the turn of the century, one more insult to a population that was already roiling amid its so-called “century of humiliation” at the hands of the West.

That public resentment fueled the Boxer Rebellion -- a violent assault on Christians and foreigners, which began in 1899 -- and was further stoked by the Boxers’ defeat at the hands of foreign troops and by the indemnities that France, Germany, Britain, and the United States subsequently demanded. The Qing dynasty was weakened, and, in 1911, protests broke out nationwide. One of the worst flash points was the nationalization of the Sichuan-Hankou railway, which ran through Hubei province and had been financed by locals. Furious over the loss of their savings, thousands of protesters gathered in Sichuan, and troops fired into the crowds, killing dozens. The attempt to crush the “Railway Protection Movement,” as these anti-Qing groups were called, ultimately failed, embarrassing the dynasty and fueling demands for a new form of government.

The next year, the Chinese imperial system -- which had stood for more than 2,000 years in the hands of various family dynasties -- collapsed. It had survived plagues, invasions, famines, civil wars, and droughts, but it was rail that finally tipped it over the edge.

One hundred years later, another railway line running through the very same province put China’s central government under pressure once again.

March is not typically the wettest month in the Yangtze River valley, but in 2012 the spring thunderstorms had been heavy. Rain pounded the newly built Wuhan-Yichang line, slowly but surely weakening the rail bed running through Hubei’s crop fields -- until finally nine kilometers of rail sank several millimeters before collapsing altogether. The entire section needed to be replaced. The line was temporarily taken out of commission, and hundreds of laborers were set to work night and day shoring the damage and laying new concrete rails with heavy equipment. The director of Hubei’s construction bureau told the Wall Street Journal that the rain was not to blame. “If the rain could destroy a railway line, then what kind of a project is that?” he asked, perhaps missing the irony.3

It was an apt question. The week before, Chinese media reported that managers of the project had not used chipped rock, known as “spall,” within the foundation, as had been ordered. Instead, they had substituted ordinary soil, which is cheaper, and had pocketed the difference. After interviewing a mole within the Ministry of Railways, the Global Times, a mouthpiece of the Communist Party, wrote that substitutions like this had been common over the years and “amount[ed] to building a house on the foundation of cake.” Indeed, the collapse spoke to a serious defect potentially underlying thousands of miles of track -- not just in the soil but in the concrete.

Concrete is the sine qua non of China’s whole rail empire because much of the track bed is elevated on giant gray stilts to carry trains over small farms, creeks, dirt roads, and whatever else might be in the way. The 819-mile line from Beijing to Shanghai, for example, is up on a viaduct for some 80 percent of its length, supported by a set of relentless marching columns, each about 15-feet thick and varying in height according to the undulating landscape. The columns were supposed to be made of a blend of gravel, cement, and a strengthening product called “fly ash,” which was to be harvested from the smokestacks of China’s coal-fired power plants.

In 2008, when the rail project went into high gear, the China Railway First Survey and Design Institute estimated that there was enough supply of high-quality fly ash to build approximately 100 kilometers of high-speed track a year. But China’s breakneck building program far exceeded that pace and, in fact, required more fly ash than all the coal plants on the planet could have produced. So some construction firms abridged the recipe to meet tight deadlines, buying substandard fly ash and using their pull with the government to bypass normal quality-control procedures.

As a result, much of the concrete in China’s 6,000-mile rail system is brittle and prone to collapse. Southwest Jiaotong University’s Zhu Ming told the South China Morning Post in 2011 that if China continues to opt for low-quality fly ash, “judgment day” could come within five years of laying the track. The infrastructural integrity of the rail, he said, will not present “small problems such as occasional cracks and slips that delay trains for hours,” but the “big problems that will postpone an entire line for days, if not weeks.”

“When that happens,” Zhu said, “the miracle of Chinese high-speed rail will be reduced to dust.” (The Ministry of Transport, the State Railways Administration, and China Railway Corp. did not respond to Foreign Policy’s request for comment.)

High-speed construction, rather than quality, seems to have been the top priority for much of China’s great high-speed railway surge. Jan Moorlag, a project manager who worked for a Dutch contracting firm on the Wuhan-Guangzhou line, recalled that his section of rail was set to open in December 2009. During the construction of a six-mile-long tunnel, however, the project started to fall behind. So a local contractor went to his Chinese boss and told him that the Ministry of Railways should be told of the delay, Moorlag explained. “Well, I think this guy would have rather have hanged himself than lose face,” he said. “The boss made phone calls all night long, and by the next morning, there were 500 extra people at the job site.” Within a week, everything was back on schedule. “The project is always delivered on time -- period,” Moorlag said.

Rail construction in China has often been marked by this bizarre melding of the superfast and the primitive. Rail construction in China has often been marked by this bizarre melding of the superfast and the primitive. The crews called up on short notice are little more than human shovel brigades, without even basic machinery like bulldozers. “There’s not much mechanical equipment on those job sites,” Moorlag said. “They have people, and people are cheaper.” Struck by the simple country muscle of this large-scale construction project, he documented the efforts in a photo album, which shows workers hauling flagstones by hand and pouring wet concrete out of handcarts.

The haste not only undermined quality control during construction, but it handicapped analysis that should have been conducted before workers ever turned the first spade of earth. “We really could not guarantee the quality of our construction work,” an unnamed engineer on some of the rail projects told Du Junxiao, an editor of the People’s Daily, in 2011. “For some projects, the steps of survey, design, and construction were all done at the same time. Some projects were handled even worse and didn’t even go through these three steps.”

Another project engineer told Du that he, himself, would never take high-speed rail for fear of his life. Du commented, “Since those who participated in the construction of the HSR [high-speed rails] dare not ride them, there must be serious problems.”4

Sure enough, on July 23, 2011, near the city of Wenzhou, a train proceeded through “dark territory” -- that is, a patch of line uncovered by signals -- and rammed into the rear of a stalled train cleared to enter the same stretch of track.

A bullet train passes the wreckage of two other high-speed trains which collided two days earlier, in the town of Shuangyu in the eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang, on July 25, 2011.

The impact knocked three carriages off a viaduct and 65 feet down to the ground below, killing 40 people. The first official response was drenched in Mao-style opacity. Newspapers across China were directed to run only brief stories. “Do not question. Do not elaborate,” warned China’s Propaganda Department in a memo. One of the mangled carriages was immediately buried on the scene (authorities claimed they needed the space for “rescue staging”), and lawyers were warned not to bring any liability cases.

Then-Premier Wen Jiabao promised to get to the heart of what had happened, and in December 2011 the government released an uncommonly blunt report that concluded, “The disastrous crash was caused by serious design flaws in the train control system, inadequate safety procedures implemented by the authorities, and poor emergency response to system failure.” A signaling device had been knocked out of commission when it was struck by lightning, and though such devices commonly have backup systems, the report suggested that the haste to get the rail up and running might have led builders to cut corners.

The government fired 54 Ministry of Railways employees after the investigation, but the top management was already gone. Five months before the crash, Liu Zhijun, the head of the ministry and architect of the massive rail expansion, had been arrested on charges of abuse of power and corruption, accused of pocketing at least $10 million. According to the New Yorker’s Evan Osnos, who has reported extensively on the ministry, Liu’s ambitions were “to bribe his way onto the Party Central Committee and, eventually, the Politburo.”

The scandal that ensued revealed that Liu had also, years earlier, used his influence to secure industry positions for his brother, Liu Zhixiang, who promptly abused his authority. Liu Zhixiang’s role as vice chief of the Wuhan Railway Bureau came to an abrupt stop in 2006, when he was sentenced to death -- a punishment later commuted to 16 years in prison -- for corruption, embezzlement, and murder. He had hired someone to stab to death a contractor who planned to expose him. (Osnos reported, “According to an official legal journal, [the contractor] had predicted in his will: ‘If I am killed, it will have been at the hand of corrupt official Liu Zhixiang.’”)

In July 2013, Liu Zhijun was convicted and given a suspended death sentence. The laudatory recounting of his accomplishments was scrubbed from official histories of the high-speed project, but the flaws in the rail network, both physical and financial, were not so easily erased. Officials later found that $28 million had been embezzled from the Beijing-Shanghai link alone.

The central government tried to show the world that it took widespread corruption seriously. In March 2013, it dissolved the Ministry of Railways and charged the Ministry of Transport, whose portfolio had never included trains, with overseeing the safety and regulation of the railways. The State Railways Administration is now responsible for inspections. And China Railway Corp., which was previously under the purview of the Ministry of Railways, manages the construction of the country’s rail system. But some things didn’t change. China Railway Corp. continued to work with its main engineering contractors, China Railway Group and China Railway Construction Corp. -- both of which are state-owned and ranked by Forbes as among the largest companies in the world.

Defenders of China’s high-speed rail have pointed out that a complex national system that carries 1.3 million passengers a day while having sustained only a few dozen known fatalities in seven years is operating quite safely -- more safely than the world’s aviation industry. But a culture of cutting corners to meet production goals pervades factories and mines as well, and China has the highest number of industrial deaths and accidents in the world. This human cost is one of the hallmarks of Beijing’s insistence on breakneck GDP growth.

Rapid growth has also incurred a high degree of financial risk. China’s formula of “spending money to make money” on infrastructure projects, such as rail, may not balance out if they do not, in the end, make money. “Are they doing high-speed rail because they need it, or are they doing this to meet a GDP target?” asked Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, in an interview with FP. “When a country tries to grow by relying on debt, it always leads to trouble.”

Rely on debt it did. In 2008, after China announced a $586 billion national stimulus package -- over $146 billion of which was directed to rail -- it became clear that the central government would not directly provide most of the money. Instead, it simply signaled to banks that infrastructure projects, which accounted for nearly three-quarters of the stimulus, would be approved. Lending targets were increased and interest rates were decreased, and Chinese banks financed a spurt of construction.

The credit infusion has been largely a family affair, as the Chinese “Big Four” megabanks -- China Construction Bank, Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and Agricultural Bank of China -- are state enterprises that take in small deposits from millions of households and lend out mountainous sums to fund national and local capital projects. Whether the ventures will ever generate enough revenue to repay the loans has often been a secondary concern to the central government. But that means banks could be left holding a slew of nonperforming loans -- and that is what has happened with rail.

Unique among today’s major world powers, China has the dubious advantage of being able to draw train lines at its pleasure while ignoring free market pressures.Unique among today’s major world powers, China has the dubious advantage of being able to draw train lines at its pleasure while ignoring free market pressures. The World Bank flagged this as a problem in 2009. “The availability and sources of railway finance are major challenges,” it reported, “particularly since many of those proposed rail projects that are driven by regional economic development aims are likely to be not commercially viable, irrespective of their wider economic and social benefits.”

The world’s longest bullet-train line, from Beijing to Guangzhou, is struggling to find its market. The eight-hour ride is not competitive with a three-hour airplane trip, and even the state-run Beijing News told its readers that the slightly cheaper fare just isn’t worth the time. Beneath the shiny exterior of China’s sleek new trains, the economic reality, at least so far, has been bleak.

Things came to a head in 2011, when the Ministry of Railways ran out of money and credit, leaving it unable to make its loan payments or pay its contractors, whom it owed hundreds of millions of dollars. Although the ministry was an arm of the central government, it had been responsible for taking out loans to fund its projects. Work on the railways screeched to a near halt until the central government stepped in, directly paying some of the ministry’s obligations and guaranteeing its debt. This reopened the credit taps temporarily.

The 2013 reorganization of the ministry was supposed to make rail operations more sustainable. But it hasn’t: The same problems are cropping up yet again. Last year, China Railway Group couldn’t service its debt while also paying its thousands of workers. In October 2013, the company reported a debt-to-asset ratio of 85 percent, indicating a high level of financial risk. And the future doesn’t appear to be much brighter-- not unless China Railway Corp., which is also struggling, manages to cough up the hundreds of millions of dollars that it owes the construction company. As if China needed a sign that all is not well, the group’s president, Bai Zhongren, fell out of a window of his fourth-floor apartment. After the news broke -- the company called it an accident, the media called it a suicide -- the stock of the state-owned, but publicly-traded company dropped more than 4 percent.

Some Chinese academics openly criticize high-speed rail as a boondoggle, predicting a debt disaster. “We can’t afford this in China!” said Zhao Jian, a professor of transportation economics at Beijing Jiaotong University, nearly shouting during an interview in his office, a spare room on an upper floor of a Maoist-era tower. “It’s like a $300 million Hollywood movie that nobody sees.”

The problem is not so much that China Railway Corp. could default. Rather, the issue is whether the problems facing high-speed rail are only one manifestation of a massive overinvestment in unneeded infrastructure -- an unsustainable approach whose risk is obscured by the fact that much of the debt is not on China’s balance sheet, but rather on the books of state banks and local governments. Chinese companies had accumulated more than $12 trillion in debt by the end of 2013, according to Standard & Poor’s. The question is how much of that debt is bad -- and how much the central government could be obligated to cover.

Beijing is already tightening credit and introducing market reforms to its banking sector, and many analysts think that the government’s ability to manage any potential defaults along the way is strong. “Behind all this,” said Peter Petri, professor of international finance at Brandeis University, “is an economy with $4 trillion in cash reserves.” In other words, China is not on the cusp of a subprime mortgage-like crisis.

But some analysts are more concerned, pointing to, among other things, China’s sharply increasing debt-to-GDP ratio. The brokerage firm Crédit Lyonnais Securities Asia, historically bullish on China, published a nervous report in May 2013 concluding that “China is addicted to debt to fuel growth” and suggesting that the country would have to go into the economic version of a rehab clinic to get spending under control. The high-speed hangover may loom for years.

Admittedly, not all of rail’s economic benefits can be expressed on a balance sheet. The official argument in favor of high-speed rail’s high-speed rollout is that it has boosted short-term employment -- 2.5 million temporary jobs within 10 years -- while leaving behind a long-term asset. Faster access from the archipelago of factories around Guangzhou, for example, means that containers full of goods can be shipped more quickly to ports. Getting slower passenger trains off the conventional rails opens them up to more freight traffic, where the real money can be made. In manufacturing, a day’s advantage can translate into hundreds of millions of dollars. With improved rail service, China can now ship three times the amount of freight that it did in the 1990s, which means it can exploit coal seams far from urban centers, just as the Qing dynasty had once hoped. And the railways allow workers to commute farther, faster -- increasing labor mobility and economic opportunity.

Chinese men walk with their luggage at the Beijing west railway station on Dec. 26, 2012.

Yet it’s not clear that your average worker can actually take advantage of this opportunity. A persistent internal complaint about China’s high-speed rail is that it was built for the rich -- high-income business travelers, like David Su of Global Capital Investments Group -- at the expense of the reliable network of conventional trains the country has operated for more than 100 years. A new piece of slang has cropped up in Beijing: bei gaosu, which means “you have been compelled to take high-speed rail.” This is roughly equivalent to You’re screwed!

One of the greatest tests of high-speed rail for China’s working poor comes during mid-winter’s Lunar New Year, when factory toilers return to their villages for reunion dinners. Over 40 days, Chinese take an estimated 258 million rail trips. But in 2013 few bought bullet train tickets because they can cost three-quarters of the average $100 monthly salary. “Saving time doesn’t matter to me. Saving money does. I think the main concern for every migrant worker is about money,” said hospital janitor Liang Xiuxia in an interview with China Daily, explaining why she was willing to sit on an ordinary train and a bus for 15 hours.

There have been signs that Chinese rail is moving in a more democratic direction, albeit under pressure. After the Wenzhou crash, officials not only slowed trains on the Beijing-Shanghai route to a top speed of 186 mph (from the previous 236 mph), but they also offered cheaper tickets. In 2011, Railways Vice Minister Hu Yadong said that “the satisfaction of the people” would now be “the basic requirement for evaluating railway work.”

Dspite its many problems, China’s high-speed rail boom has resonated around the world -- even, to some extent, in the United States.

To date, the American experience with high-speed rail has been an expensive disappointment. Amtrak spent $661 million for what it called the Acela between Boston and Washington, but the train’s ungainly design and shared tracks keep its average speed at a poky 75 mph. So in 2009, President Barack Obama guaranteed $8 billion total in matching funds to any states willing to embrace the vision of a 180 mph ride between cities. Over the next two years, Republican governors killed high-speed rail projects in Ohio, Florida, and Wisconsin, leaving California as the largest recipient of the federal largesse. Even there, lawsuits over cost and environmental issues have hampered progress, but Gov. Jerry Brown remains a voluble supporter. He rode the line from Shanghai to Beijing on a tour in April 2013. “People here do stuff,” the governor told reporters, with obvious envy. “They don’t sit around and mope and process and navel-gaze. The rest of the world is moving at Mach speed.”

California’s interest in China is being reciprocated. Another passenger on Brown’s train was Jiang Lay, a designer and engineer for Tangshan Railway Vehicle Co., a China-based locomotive manufacturer. “We are very interested in California,” he told the Los Angeles Times.5 “We are very confident that our Chinese technology can be successful in America.” Manufacturers are already plotting the same joint ventures that first brought traction motors and signals to China. And the California High-Speed Rail Authority has said it may tap sovereign wealth funds -- such as the China Investment Corp., with which talks have already begun -- to defray the $68 billion needed to build a line connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco. This would put big rail debt on two continents, even as the economic benefits are still being sorted out.

Meanwhile, Morocco is planning to lay tracks for a real-life Marrakesh Express to Tangier that will stretch 350 miles. By the end of 2015, Saudi Arabia expects to run its first test of the Haramain High-Speed Railway, designed to whisk pilgrims from Jeddah’s airport to Mecca -- ordinarily an hour’s drive -- in around 30 minutes. Vietnamese officials recently considered a scheme to unite the former warring capitals of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City with a 720-mile track.

China is only too happy to help. Experienced gandy-dancing firms from Beijing and Shanghai are proposing lines in places as disparate as Kenya, Israel, Colombia, Venezuela, Turkey, and Russia in an official sales policy that the central government has termed “Go Abroad.” In Burma, a Chinese firm has partnered with the government to build train-production facilities. If nothing else, China is now the undisputed leader

in this sector, or as a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering recently told the reliably nationalistic Global Times, “High-speed rail is to China what watches are to Switzerland, electric appliances to Japan, and machinery to Germany.”“High-speed rail is to China what watches are to Switzerland, electric appliances to Japan, and machinery to Germany.”

Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions are in play as well. In 2013, the government of Laos agreed to let a Chinese company blast a railway through its hills to connect China’s Yunnan province to Singapore by 2019. There is serious consideration of connecting Germany to a “New Silk Road” of Asia, in which all rapid-transit lines lead to Beijing. China’s leaders now use the phrase “high-speed rail diplomacy.” With tracks that will reach inside other Asian countries, China is creating a whole new economic paradigm -- one that it will control because high-speed rail isn’t usually built to ship cargo. It moves something even more important: people.

With high-speed rail, China will be able to supplant small businesses in neighboring countries, flooding the zone with its own class of mobile merchants. This will build grassroots financial and cultural influence that will quickly translate into political clout. The reshaping of Southeast Asia on a firmament of railroad tracks would give China an enormous advantage in dictating regional trade policy. Militarily, the bullet trains will serve a function understood by every fighting general since Nathan Bedford Forrest: “Git thar fustest with the mostest.” High-speed rail would provide China with almost unbeatable regional power projection in Asia.

Of course, all this assumes the empire of rail can find its way to firmer structural and financial footing. China displayed boldness and grandeur in deciding to wire up its major cities with such a futuristic tool. Now it just has to find a way to make it work.

|

评分

-

1

查看全部评分

-

|