|

|

【中文标题】三星之战

【原文标题】Samsung's War at Home

【登载媒体】商业周刊

【原文作者】Cam Simpson

【原文链接】http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-04-10/deaths-at-samsung-alter-south-koreas-corporate-is-king-mindset#r=most popular

黄相棋的家是一绿色的混凝土平房,这位58岁的韩国出租汽车司机坐在地板上。他手中握着一只小包,由于多年搁置,亮白色已经变成暗灰色。他拿出一张照片,上面是13个微笑的女孩。她们都是三星电子的员工,下班后排成三排,互相倚靠着。她们身后的树叶呈深秋的金黄色。

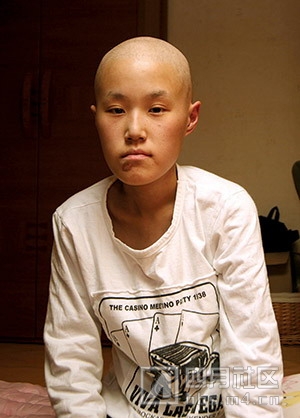

家中的黄游美,这是她在2007年3月6日去世前几个月的照片。

黄说:“这里。”他指着中间的两个女孩。她们都在同一家半导体厂做同一份工作,在同一个车间里的同一条流水线上,在同一个化学容器中负责浸泡电脑芯片。她们都患上了一种癌症,叫做急性骨髓白血病。其中一个是他的女儿——游美。在韩国,只有十万分之三的人死于白血病。黄说:“她们在一起工作,她们都死了。”这张照片是黄手中仅有的已故女儿的几个回忆之一。

这两个女孩,以及其他几十名患有白血病和罕见癌症的三星工人的故事,在韩国已经尽人皆知。到二月和三月,韩国人应该可以看到两部电影,内容就是黄和其它几个家庭与韩国最大、最有影响力的公司之间,历经7年的斗争。

黄一头灰白色的头发,眼睛下面有两个很深的酒窝,他在电影中的角色由47岁、出演过70部影片的朴哲民扮演。他在影片《再次承诺》中的角色与一个虚拟的公司“金星”相抗争。《韩国先驱报》说这部影片是“韩国电影届和韩国民主制度意义重大的成就”,不仅仅因为影片的质量,还因为它的制作方式。导演和制片人没有得到任何大财团的资助,他们通过crowdsourcing网站向数百人募集了200万拍摄预算中的15%,还从100个小投资人处募集了超过一半的资金。这是韩国以这种方式制作的第一部电影。

纪录片《耻辱帝国》在3月6日上映,制作期为三年,它深入展示了黄和其它三星工人家庭的状况。影片主要关注黄发起的大规模运动,向世人展示电子工厂,尤其是半导体工厂中使用致癌物的事实。在他之后,活动人士在若干家三星工厂中相继发现了58起白血病和其它血液类癌症病例。三星拒绝就这篇文章讨论具体细节,而是在一份声明中说,它已经在2011年投入了8800万美元维护、改善安全相关的基础设施。

运动的目的是向一家韩国政府保险基金争取致癌员工的经济赔偿。黄和影片制作方等人把一场谈判变成了有关这个国家经济腾飞所付出的代价的一种韩国文化,带动经济增长的主要是三星和其它几家技术产业机构,它们是很多韩国人的骄傲。这场运动让人们开始重新检视韩国发展的代价,当今的繁荣是建立在一个独裁政府与被赋予巨大权力的本土企业联手之上的。

首尔以南大约20英里的一片被围栏环绕的厂区里,器兴半导体厂坐落在一个人工水库丛林茂密的岸边。这家工厂外观像一个扁平的白盒子,巨大的烟囱和管道矗立在屋顶上,前面有一个熟悉的蓝白色三星标志。这家工厂于1984年建立,三星电子在当时80%的收入来自半导体芯片,而它是这个国家最大的芯片工厂。器兴的生产线是人人向往的工作场所。

很多韩国人非常尊敬三星公司,部分原因在于它的成功标志着在那场导致国家分裂、数百万人死亡、无数人陷入赤贫的战争后韩国的崛起。1961年,朝鲜战争陷入僵局之后的8年,韩国的人均GDP只有92美元,甚至低于苏丹、塞拉利昂和刚果民主共和国。到了去年,韩国的经济总值位居世界第15位,大约24%的GDP来自三星集团的收入。这家企业集团由数十个产业组成,其中包括一家保险公司、一个重型机械公司、世界第二大造船厂,当然还有三星电子。

游美家住在东北部港口诚实束草,与日本隔海相望。她的父母没有钱供她上大学,所以当2003年器兴工厂的招聘启事出现在她的高中校园中时,引起了他们的兴趣。三星希望在游美这一届毕业生中招聘排名前三分之一的女孩。她满足了基本的条件:不错的成绩、良好的出勤记录、没有受到过处罚,她还通过了身体检查。她的父亲说:“参加完面试之后,她告诉我应聘成功了。我非常高兴,因为三星是韩国最好的企业之一。”

2003年10月的一天早晨,游美和她的父母乘黄的出租车来到束草汽车站。她和班里其他应聘成功的女孩子们一起搭乘汽车,前往西边三小时车程的器兴。老师和家长们前来送行,他们的兴奋和喜悦掩盖了内心的紧张。黄说:“这是游美第一次离开家。”

器兴工厂的大门之后,女孩们每四个人住在一个高层公寓的房间里。白色的大楼未经修饰,只有楼侧淡紫色的韩国字标识出以花卉命名的公寓楼。黄说他的女儿住在丁香楼。这里不接受访客,甚至不允许家属探望。在接受了几个星期的培训之后,女孩子们开始工作。

纪录片《耻辱帝国》场景。

据法庭记录,游美被安排到3号流水线。她每天用白色的清洁间服装、手套和口罩把自己从头到脚罩起来,这些东西不足以保护她,但可以维持半导体生产车间的无尘化环境。这条流水线生产三星公司用来驱动小型工具的逻辑芯片,而不是储存数据的设备。游美的第一项工作是所谓的“滤渗”,第二项工作是在同一条流水线上“蚀刻”。

韩国法院的一个工作小组后来发现,在一天8小时的工作中,游美暴露在一个含有潜在危险化学物质的电池周围,以及刺鼻的味道和电离辐射中。一个同样操作蚀刻的同事李英淑出现了皮肤过敏反应,需要定期治疗。

除了感觉到疲劳,游美并没有和家里人抱怨过其它感受,知道2005年10月底她给家打电话,说“她觉得恶心、头晕、呕吐”。一位同事把她送到器兴厂区内的三星医务室,医务人员抽取并监测了她的血样。他们说游美的血样异常,这里无法进一步处理。她立即被送到最近的一家大医院,她的父母开着出租车来看她。

医生告诉黄,他的女儿患上急性骨髓白血病,并请他们同意立即进行治疗。他说:“我的眼前一片漆黑,我绝望了。”他不大了解白血病,但知道这通常会致命。她的母亲说,游美极为悲痛,尽管以上说她有很大的康复几率。

这位20岁的女孩开始化疗,她的头发掉光,经常感到恶心和乏力。在医院治疗一个月之后,黄开车把她接回束草,她依然住在自己原来的房间里。这家人每周两次开车去医院治疗和化验,游美在2006年夏天再次住院。就在那个时候,她听说和她同在3号流水线上工作的同事李英淑,就是那个皮肤过敏的人,也患上了同样的疾病。李是两个孩子的母亲,其中一个刚出生不久。她在那一年的7月13日被确诊,5个星期之后去世。

李的突然去世,让黄的脑海中产生了疑问。他开始询问游美工作中的细节,尤其是那些化学芯片溶液。黄当时还不知道,但急性骨髓白血病的病因被很多科学家认为是暴露在致癌物中。

三星电子器兴工行人力资源部的管理层一直与黄保持联系,了解游美的状况,公司也一直在为游美支付治疗费用。黄说,在骨髓移植之前,公司共支付了18000美元。之后,黄告诉他们,他打算向政府提出工伤赔偿申请,来支付游美未来的治疗费用。黄说,从那一刻开始,三星翻脸了。

半导体的生产尽管在无尘车间中进行,但它从来就不是一个干净的生意。芯片制造商从硅谷早期开始就使用极为有害的化学物质。加利福尼亚圣克拉拉县是美国有毒废物填埋场最多的地方,从二十世纪九十年代到本世纪初,有大批的企业在诸如英特尔、惠普、飞兆、AMD和国家半导体等行业领先者的挤压下,退出市场。

由于化学物质对硅谷的环境影响让人们担忧,在工厂中上班的人们已经产生了足够的警惕。生产半导体及其副产品需要复杂的流程,包括把线圈放在硅片中,这个过程中所使用的化学物质包括致癌物,比如苯、三氯乙烯、乙撑氧、三氢砷化、三氧化二砷。这些混合物经常被用来浸泡芯片,加上为减少厂内灰尘而刻意减少通风,导致这些工厂无法通过严格的安检,因此半导体生产商纷纷离开加利福尼亚,转战亚洲低工资地区。

由产业方所资助的研究及相关调查显示,半导体生产与工人的癌症之间没有统计学上的显著关联,而其它一些研究显示这种关联的确存在。双方观点的拉锯几乎出现在所有相关问题的讨论上。

黄相棋(中)面对三星的保安。

黄对于半导体工厂历史上的毒性事件一无所知,他没有受过太多的教育,出身于一个儒家思想浓厚的家庭,信奉顺从和人性的良善。所有这些都让他在面对三星公司的高管时处于不利的地位。2007年1月,李去世几个月之后,游美的病情恶化,卧床不起。器兴的三星高管来到束草。黄不顾三星的反对,坚持要提起工人补偿申请。他在离家几分钟路程的一家咖啡厅与这些人见面,会面的结果令他猝不及防。

黄说:“他们没有询问游美的病情,那四个人冲我大喊大叫。”他们说,他女儿“的病与三星无关,‘为什么要让三星承担责任?’”20分钟的会面过程他一直在流泪,“我非常非常气愤”。黄离开咖啡厅,走路回家。到家之后他躲着游美,知道她肯定会发现他的表情。三星拒绝评论其高管与黄会面的详情。

游美的病情愈加恶化,黄暂时把申请赔偿的事情放在一边,他们又开始每周前往医院治疗。2007年3月6日,一家人从医院出来之后,游美躺在出租车后座上,黄开车回束草。黄说,快到家的时候,“游美说:‘好热。’”于是我把窗户打开,只开了一点点。但是一会她又说:‘好冷。’我就把窗户关上了。”等了一会,他的妻子扭过头向后看,突然大叫。“我停下车,打开后门,发现她已经没有呼吸,眼睛已经翻白。游美的母亲哭起来,用手把她的眼皮合上。我脑袋一片空白,不知所措。不知道过了多久,我发现自己还站在高速公路旁边。”

他打电话叫来了家人和朋友,把车直接开到了束草的殡仪馆。按照韩国的习俗,游美的葬礼在当天晚上举行。三星器兴工厂的几位高管前来吊唁,其中包括他在咖啡馆见过的那四个人。葬礼期间,黄走到外面呼吸海边的新鲜空气,发现三星的高管跟着他出来。黄说:“他们告诉我,葬礼之后他们一定会给付赔偿款。我什么也没说。”

大约一个星期之后,三星的高管再次来访。在一家生鱼片餐厅坐下之后,他们说公司不会赔偿这个家庭。他说:“他们又改主意了,”因为他们再次坚称游美的癌症与工作无关。黄起身离开餐厅。他绝不相信,在同一个车间工作的两个年轻、健康的女孩,没有家庭病史,几乎同时患上罕见的癌症,怎么会和工作没有关系。他怀疑还有其它病患,但无法得知。

黄在2007年6月1日来到韩国职工补偿和福利服务部,填写了一张申请表。与美国政府的做法类似,韩国的企业需要缴存基金,由政府来支付工伤和疾病的赔付。赔付金额通常并不高,仅够支付医疗、误工和丧葬费用。

游美去世之后,黄联系了所有可能帮助他调查的人,他试图寻找器兴的19000名工人中是否还有类似的病例。他尝试联系政府官员、党派负责人、活动人士、人权组织、记者等等,但他得到的仅仅是同情和慰问。他需要了解是否有其它的病例,以及她究竟是暴露在何种化学物质中,这样他才可以向韩国职工补偿和福利服务部提出一个有效的申请。他说:“但是没有人愿意听我说话。”这时,当地的一名记者把他介绍给30岁的活动人士李钟兰。

2013年,工人家属在三星的首尔总部抗议。

李钟兰曾经听说过半导体厂的工作可能导致流产,但从不知道还会引起癌症。她收集了一些方案,向20几家机构筹集了一小笔资金,成立了一个名为“Banolim”的组织。她是唯一的组织成员,还有一些家属作为志愿者加入。

黄开始频繁出现在三星工厂的大门前,他身上挂着一个大的广告牌,印着他女儿患病时光头、憔悴的照片。他向路人发放传单,希望引起别人关注。慢慢地,有其它一些家属加入了他的抗议活动,部分媒体开始关注,抗议的规模越来越大。

2009年5月,在他提出申请两年之后,韩国职工补偿和福利服务部拒绝了黄的申请。他们还拒绝了Banolim代为提出了三项其它申请,其中包括李英淑的鳏夫的请求。政府内负责健康和安全的官员在6家半导体工厂中进行了病理学调查,据法庭的记录,他们说尽管发现女性员工中白血病例和非霍金奇淋巴瘤的发病率死昂对较高,但整体来看“并不显著”,不足以证明与半导体的生产过程有关。他们并没有公开原始数据。

Banolim通过与工人和家属交谈,共发现了58例白血病。他们还发现了其它相关疾病和数十起的癌症病例,包括乳腺癌和脑瘤。一组韩国大学科学家和研究人士为一份医学期刊开展一项研究,他们利用这些病例专门关注那些与半导体生产过程直接相关的工人,尤其是器兴工厂。他们进一步把研究范围缩小到近三年确诊的病例上,他们只关注那些已经证实与化学物质和放射因素相关的癌症,即白血病和非霍金奇淋巴瘤。三星拒绝就这项研究发表评论。

在器兴工厂抽取的的样本中,科学家和研究人员发现了17名患病的工人,其中11人为年轻女性,平均年龄26.5岁。由于公司的不配合,研究小组无法获取员工离职率等其它能证明因果关系的数据,但他们说他们的发现引起了严重的关注。

黄和其它家属被迫向韩国的司法系统上诉政府的决定,这是韩国的行政模式。但是当提起诉讼之后,家属们发现韩国职工补偿和福利服务部的辩护律师不是政府出钱聘请的,而是三星公司出钱。这等同于公司正式干涉并袒护韩国职工补偿和福利服务部,即使三星不需要承担任何赔偿金额,这也绝对是一个罕见的举动。他们聘请了这个国家顶级律师事务所来为这起案件做辩护。

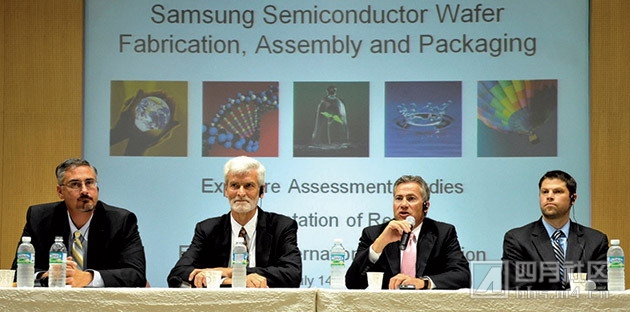

三星在2011年召开的新闻发布会,来自美国的专家对芯片厂的安全性做调查。

2010年,韩国最大的电视网络韩国放送社播放了一部有关这起事件的60分钟短片,节目之后出现了更多的病例汇报。Banolim声称三星内部人士曾经秘密与家属接触,表示原意支付赔偿金,条件是他们撤回赔偿申请,与Banolim断绝联系,在公开场合保持沉默。这和常见的诉讼和解不同,因为三星并不是被告人,这只不过是政府保险赔偿申请。三星不承认有过这样的表态。

三星在法庭上直接面对受害者家属,一些人猜测正面冲突不可避免。2010年12月15日,器兴工厂的一名三星公司高管来到束草黄的家中。他说:“我想我们可以付给你能让你满意的钱,但是你不可以和任何人说,否则我们的处境会跟尴尬。”

黄问道:“你是说你会给我钱,对吗?”

高管说:“我只是希望你不要说任何对三星不利的话。就目前来看,我觉得你很有可能无法得到保险的赔偿金。”

黄在放送社的帮助下,偷偷把谈话的过程录音,2011年在电视台被播出。同时还播出了其他家属接到了类似的条件,其中包括朴智研——23岁女性,2010年3月死于白血病——的家属。她的母亲说,在女儿葬礼那一天,她的银行账户里多出大约33万美元。她还说公司的代表“让她不要与工会成员见面,撤回起诉”。三星拒绝就录音事件和对朴智研付款的事件发表评论。

2011年3月,首尔行政法院的三人法官小组听取了黄的上诉申请,同时也听取了李英淑的鳏夫和其它三个家庭的上诉申请。一个月之后,首席法官在公开法庭中宣读了他的裁决和意见。他做出了有利于黄和李的鳏夫的判决,并命令政府赔偿基金支付赔偿款。

法官小组驳回了其它三个家庭的上诉申请,他们详细描述了手中的证据和每名工人的具体工作,包括接触的化学品、周边的辐射、通风系统和器兴工厂的操作流程。(他们发现其它工厂的流水线比器兴更加现代化,也更安全。对于两名男性工人,他们认为缺少男性工人病例大幅增加的关键性证据。)

三个星期之后,三星与他们聘请的美国咨询公司Environ联合召开新闻发布会,声称咨询公司并未发现工人接触化学品与白血病之间有统计学意义上的重大关联。韩国职工补偿和福利服务部对于赔付两名女性工人家庭的判决提起上诉。

Banolim目前手中还有大约40个案子,其中有的在韩国职工补偿和福利服务部中等待批准,有的已经在走司法程序,韩国人对此非常关注。即使再次之前,福利服务部的高层人士已经开始尝试化解矛盾,他们给一些曝光率比较高的申请批准了赔偿。去年年底,法院就另一起工人致死案件做出了类似的裁决,称有研究显示三星的芯片工厂存在漏洞,未能全面保护工人的健康和安全。政府对于黄的案件的判决正在上诉过程中,游美去世7年之后,他依然在等待最终的决定。

三星说员工是他们最宝贵的财产,公司的目标是营造“一种坚定不移奉行安全管理和最佳操作流程的企业文化”。它还说,三星在2007年是第一个引入实时监控化工品技术的半导体制造商,这个技术改善了工厂内部的空气质量。“我们对于前三星员工家庭的悲剧感到极为悲伤,也非常关心他们与疾病做斗争的过程。但是我们依然需要重申,独立研究机构并未发现员工的疾病与工作环境有直接的关系。”它还说正在为员工家属提供资助,但并未透露具体金额。

担任韩国国会议员18年的李美京一直坚定地支持黄和其它三星员工的家属。我们有机会在国会投票的间隙在国会大厅外的咖啡厅见到她,她说三星对政治、媒体或甚至法律都有强大的影响力,很多韩国人都称自己的国家为“三星共和国”。她说情况慢慢在发生变化,韩国公司的权力逐渐得到了一些限制。她说到,2008年对三星公司的一次调查主要针对用来贿赂法官、检举人和政客的贿赂基金。公诉人最终宣布没有发现贿赂的证据,但他们依然以逃税的罪名起诉三星电子的董事长李建熙,并将其定罪。他支付了大约1亿美元的罚金,并被判缓刑。

对于影片《再次承诺》,三星公司在它的一个韩国博客上发表了一份颇有意思的评论。评论人是公司的高管金善宾,这很有可能是经过公司内部批准的措辞。金在评论中说他自己的女儿对自己态度非常不友好,因为她和朋友含着眼泪看完了这部影片。在以前,她一直为父亲的工作感到自豪。

“作为一个父亲,我完全理解黄的损失,让他一个人奋斗7年,公司也有一定的责任。但是,电影毕竟是电影,扭曲事实是错误的行为。”金也在器兴工厂工作过,他还写到:“我知道,公司和员工都在努力创造一个安全的工作环境,所以我对自己工作场所的安全性完全放心。”

原文:

Just inside his single-story home, built of concrete blocks and coated in turquoise paint, Hwang Sang-ki, a 58-year-old Korean taxi driver, sits on a floor mat. He’s clasping a small handbag, once bright white and now dull after years on a shelf. He pulls out a snapshot of 13 smiling young women, all co-workers at Samsung Electronics (005930:KS), off-duty and posing in three rows, each embracing or leaning into the other. The leaves of a tree behind them are turning golden in the autumn chill.

Hwang Yu-mi at home, a few months before her death from leukemia on March 6, 2007.

“Here,” says Hwang, pointing to two women in the center of the group. Both had the same job at the same semiconductor factory, on the same line, standing side by side at the same workstation, dipping computer chips into the same vat of chemicals. Both got a particularly aggressive form of the blood cancer known as acute myeloid leukemia. One was his daughter, Yu-mi. In South Korea, only about 3 out of every 100,000 people die of leukemia. “They worked together, and they died,” says Hwang. The snapshot is among a few private memories Hwang keeps of his late daughter.

The story of the two women, and dozens of Samsung workers with leukemia and other rare cancers, is now a very public one in South Korea. In February and March, Koreans could see two movies depicting the seven-year battle led by the Hwangs and other families against Korea’s biggest and most influential corporation.

Hwang, who has deep smile wrinkles radiating from the sides of his brown eyes and a buzz cut of salt-and-pepper hair, is portrayed by Park Chul-min, a 47-year-old actor with 70 film roles in his career. His character in Another Promise battles with the fictitiously named company Jinsung. The Korea Herald called the movie “a meaningful achievement in Korean cinema, as well as for Korean democracy,” not so much because of its quality but because of how it was made. Without a major studio backer, the director and producer raised almost 15 percent of the $2 million budget from hundreds of individuals via crowdsourcing and more than half from about 100 small investors. It’s the first Korean film produced this way.

Empire of Shame, a documentary, hit theaters on March 6. Three years in the making, it was shot with intimate access to Hwang and other families of Samsung workers. It focuses on the broader movement Hwang launched to illuminate the use of carcinogens in electronics factories, especially semiconductor plants. Since he began, activists have discovered 58 cases of leukemia and other blood-related cancers across several Samsung plants. Samsung declined to discuss specific cases for this article, saying in a statement that it spent about $88 million in 2011 on the maintenance and improvement of its safety-related infrastructure.

The main goal for the movement is to wrest compensation for cancer-stricken workers from a Korean government insurance fund. People such as Hwang and the filmmakers are pushing a conversation into mainstream Korean culture about some of the costs of the country’s miraculous economic rise, which happened in large part on the shoulders of Samsung and the rest of the technology industry, global symbols of pride for many Koreans. It’s driving a reexamination of trade-offs in South Korea’s past, when the foundation for today’s prosperity was built by an authoritarian government working hand in hand with domestic corporate partners who were given great power in exchange for rapid growth.

About 20 miles south of Seoul, inside a fenced and secured compound, the Giheung semiconductor factory rises near the wooded shores of a man-made reservoir. The factory is a wide white box sprouting smokestacks and curled tubes from its roof, with Samsung’s familiar blue-and-white logo across its front. Built in 1984, the plant was the leading semiconductor factory in the country at a time when chips accounted for about 80 percent of all revenue at Samsung Electronics. Giheung’s assembly lines were a prestigious place to work.

Many Koreans revere Samsung. In part that’s because its success mirrors their own climb from a war that divided a country, killed millions, and left millions more destitute. In 1961, eight years after the Korean War ended in a stalemate, South Korea’s per capita gross domestic product was $92, less than that of Sudan, Sierra Leone, or the Democratic Republic of Congo. By last year, South Koreans had the world’s 15th-largest economy. Almost 24 percent of GDP came from the revenue of the Samsung Group, a conglomerate made up of dozens of businesses including a life insurance company, a heavy-construction company, the world’s second-biggest shipbuilder, and of course Samsung Electronics.

Yu-mi’s parents couldn’t afford to send her to university, so a recruitment notice from the Giheung factory caught her eye in 2003 when it appeared at her high school in the northeastern port city of Sokcho, along the Sea of Japan. Samsung wanted young women from the top third of Yu-mi’s graduating class. She met the initial criteria: decent grades, solid attendance, and no record as a troublemaker. She also passed a required medical exam. “She had an interview, and she told me she was accepted,” her father says. “I was very happy, because Samsung is one of the best companies in Korea.”

One morning in October 2003, Yu-mi and her parents climbed into Hwang’s taxi and drove to Sokcho’s bus terminal. Other young women from her class hired by Samsung were boarding the same bus for Giheung, about three hours west. Teachers and parents gathered for a send-off, their cheers and waves masking their nerves. “It was the first time that Yu-mi left home,” Hwang says.

Behind Giheung’s gates, the women lived four to a unit in high-rise dormitories. The white concrete towers are unadorned, except for some mauve trim and Korean script on each building’s side spelling out the flowering shrub it’s named for. Hwang says his daughter lived in Lilac. The almost identical Forsythia is next door. No visitors were allowed, not even family. After a few weeks of training the women went to work.

Still from Empire of Shame, a documentary about efforts by Hwang and others to get compensation for Samsung workers

Yu-mi was assigned to Line 3, according to court documents. She covered herself head to toe each day in a white cleanroom suit, gloves, and cloth mask—not so much to protect herself but to maintain a dust-free environment for the semiconductors. Her line produced the Samsung logic or “system” chips that drive gadgets, rather than the ones that store data. Yu-mi’s first job involved a process known as diffusion. Her second was in “wet etching” on the same line.

Throughout her eight-hour shifts, Yu-mi was exposed to a battery of potentially dangerous chemicals, fumes, and ionizing radiation, a panel of Korean court judges later found. One of her co-workers in wet etching, Lee Suk-young, had developed skin irritations that required her to get regular medical treatment.

Other than describing her fatigue, Yu-mi didn’t complain to her parents, until she phoned home late in October 2005, saying “she felt nauseous, dizzy, and she was vomiting,” her father says. One of the other workers brought Yu-mi to a Samsung infirmary in the Giheung compound, where personnel drew and tested her blood. They told Yu-mi something was wrong, something they couldn’t deal with. She was admitted urgently to the closest major hospital. Her father and mother got into his taxi and headed out to see her.

The doctor told Hwang his daughter had acute myeloid leukemia and asked for permission to start treating her immediately. “I thought I was blinded. I felt darkness and hopelessness,” he says. He knew little of leukemia but did know the disease often could be fatal. Yu-mi was inconsolable, her mother says, even though the doctor gave her good odds for a recovery.

The 20-year-old started chemotherapy right away. She lost her hair and was nauseous and constantly exhausted. She was hospitalized for about a month before Hwang drove her back to Sokcho, where she took up residence in her old room. The family drove across the country twice a week for treatments and exams, and Yu-mi was hospitalized again in the summer of 2006. That’s when she heard that her co-worker on the same bay of Giheung’s Line 3, Lee Suk-young, the woman with the skin irritation, shared the same disease. Lee, a mother of two, including a newborn, was diagnosed on July 13 of that year. She died five weeks later.

After Lee’s sudden death, questions swirled in Hwang’s mind. He started asking Yu-mi details about her work, especially the chemical chip baths. Hwang didn’t know it then, but acute myeloid leukemia had been proven by scientists to be one of the cancers most clearly caused by exposure to carcinogens.

Samsung executives from Giheung’s human resources department kept in regular contact with Hwang to check on Yu-mi’s condition, and the company had been depositing money in her bank account to help with her care, including the equivalent of about $18,000 before a bone marrow transplant, Hwang says. Then Hwang told them he wanted to file a worker’s compensation claim with the government to help cover Yu-mi’s ongoing care. At that point, Hwang says, everything changed: Samsung turned hostile.

Despite the reliance on cleanrooms, semiconductor manufacturing has never been a particularly clean business. Chipmakers have been using extremely hazardous chemicals since the early days of Silicon Valley. Santa Clara County, Calif., had more Superfund sites than any county in the U.S. following a wave of designations in the 1990s and 2000s, including those left behind by industry pioneers such as Intel (INTC), Hewlett-Packard (HPQ), Fairchild Semiconductor (FCS), Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), and National Semiconductor (NSM).

As the impact of chemicals dispersed into the Valley’s environment caused concern, alarm bells also sounded over the far greater concentrations workers potentially faced inside the plants. Chemicals used to make semiconductors, or byproducts created from the complex manufacturing processes involved in putting circuits onto and into silicon wafers, include known and likely human carcinogens such as benzene, trichloroethylene, ethylene oxide, Arsine gas, and arsenic trioxide. The chemical cocktails, often used as chip baths, and a lack of ventilation intended to reduce the dust inside semiconductor plants fell under increasing scrutiny—just as semiconductor manufacturing was departing California and the rest of the U.S. for the lower-wage shores of Asia.

Industry-backed research and other studies have suggested there was no statistically significant connection between semiconductor production and cancers among workers. Other research suggested there was, yielding an epidemiological tug of war familiar to almost any debate where science weighs on high-stakes questions of liability.

Hwang knew nothing of the semiconductor industry’s toxic legacy. He’s uneducated and from a humble background in a culture shaped by Confucian values of subordination to authority and the good of the group. All of this put him at a severe disadvantage when dealing with executives from a company such as Samsung. In January 2007, a few months after Lee’s death, Yu-mi had relapsed and was confined to her bedroom when four Samsung executives from Giheung came to Sokcho. Hwang, who had insisted he would file for worker’s compensation despite objections from Samsung, met them at a cafe a couple of minutes from his home. He was unprepared for the reception he got.

“They didn’t ask me about Yu-mi’s condition,” Hwang says. “The four of them were raising their voices against me.” The executives, Hwang says, insisted his daughter’s “disease has no relationship with Samsung, so ‘Why are you blaming Samsung?’ ” He says he spent much of the 20-minute meeting in tears—“I was upset, I was really upset.” Hwang left the cafe, making the short walk home. Once there, he tried to avoid Yu-mi, knowing he couldn’t hide his feelings. Samsung declined to comment on its executives’ interactions with Hwang.

Yu-mi’s health declined, and Hwang put his desire to file a compensation claim out of his mind. The family renewed its trips back and forth across the country for treatment. After one such day at the hospital, on March 6, 2007, Yu-mi lay down across the back seat of her father’s cab as they began the drive back to Sokcho. As they got closer to home, “Yu-mi said, ‘It’s very hot.’ So I opened the windows, just a little,” Hwang says. “But after a little while, she said, ‘I’m cold,’ so I closed them.” Not long after, his wife looked over her shoulder and cried out. “I pulled my car to the side. I got out and opened her door, and she wasn’t breathing, and her eyes were rolled back. I could see her eyes had gone white. Yu-mi’s mother was crying. Then she closed Yu-mi’s eyes with her hand. I was at a loss. I didn’t know what to do. Then, after a while, I realized I was standing alone on the highway.”

He called family and a few friends and, arriving in Sokcho, went straight to a funeral parlor. Yu-mi’s visitation would be that night, as is the Korean custom. Executives from Samsung’s Giheung plant came, Hwang says, including the four men he’d met with at the cafe. At one point, Hwang stepped out for a breath of sea air. He says the senior-most Samsung executive followed. “He told me, ‘After the funeral, I will make sure there is compensation,’ ” Hwang says. “I didn’t say a word.”

About a week later, Samsung executives came back, telling Hwang over a sashimi dinner that the company wouldn’t compensate the family. “They had changed their attitude,” he says, because they again insisted her cancer wasn’t connected to her job. Hwang got up and left the restaurant. He didn’t believe there was a chance two healthy young women—partners at the same workstation—could die from the same rare disease without family histories and without some connection to their work. He suspected there were others but had no way of knowing.

Hwang went to the office of the Korean Workers Compensation and Welfare Service, known as KCOMWEL, and filled out an application on June 1, 2007. Like similar government programs in the U.S., Korean employers pay into a fund; any compensation for accidents or illnesses is paid by the government, not the company. Benefits are modest, covering medical bills, lost wages, and funeral expenses. There’s no need to demonstrate employer negligence.

Since Yu-mi’s death, Hwang had been calling or visiting just about everyone he thought might help him investigate whether others among the 19,000 production workers at Giheung were sick. He tried government officials, political parties, activists, civil society groups, journalists, and more. He found some sympathy but never much help understanding what had happened to Yu-mi, if there were other cases, or what kind of chemicals she was exposed to, all of which he might need to file an approvable claim with KCOMWEL. “No one would listen,” he says. Then a local journalist introduced him to a 30-year-old labor activist named Lee Jong-ran.

Workers’ families stage a protest at Samsung’s Seoul headquarters in 2013

She had heard about semiconductor work causing miscarriages, but nothing about cancer. She put together a proposal and raised a small amount of money from about 20 organizations, forming a group called Banolim. She was the only employee. Families and others volunteered.

For his part, Hwang began showing up at Samsung’s gates wearing a sandwich board featuring a giant photograph of his daughter, bald and wasted by her disease, as he passed out leaflets asking people to come forward. A few did. Soon families staged small demonstrations. Dribbles of press attention followed. More families emerged.

In May 2009, KCOMWEL rejected Hwang’s claim, almost two years after he filed it. The agency also rejected three others organized by Banolim, including a claim from Lee Suk-young’s widower. Government health and safety officials had conducted an epidemiological study of six semiconductor plants. According to court records, they said that although they found elevated levels of leukemia and statistically significant increases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among female workers, the overall increases among them were “not statistically significant” enough to prove causation within the semiconductor industry. They did not make their raw data public.

By speaking to workers and their families, Banolim discovered the 58 cases of leukemia. They also found other related diseases and scores of other cancer cases, including breast cancer and brain tumors. A group of Korean university scientists and researchers, conducting a study for a peer-reviewed medical journal, would later use these cases to focus exclusively on workers who they could prove were involved directly in semiconductor production—solely at Giheung. They narrowed further to those diagnosed within about a three-year window. They looked only at a group of related cancers proven to have strong causation by, or contributions from, chemicals and radiation—leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Samsung declined to comment specifically on the study.

Within the window they drew at Giheung, the scientists and researchers found 17 production workers with such diseases. Eleven of them were young women, average age 26.5. Because the company didn’t cooperate, the group didn’t have employee turnover or other data needed to prove a causal relationship. They said what they did find was cause for serious concern.

Hwang and the other families were forced to turn to South Korea’s court system to appeal the government’s denial of benefits. That’s how the Korean system works. But after filing suit, the families discovered the defense of the agency’s decision was being paid for not just by the government but also by Samsung. The company formally intervened in the case on the side of KCOMWEL—a rare move, even though Samsung would not be responsible for any benefit payments—and put lawyers from one of the nation’s top firms on the case.

A Samsung press conference in 2011, with experts from the U.S. who conducted a chip plant safety investigation

In 2010, the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS), the largest of South Korea’s four major television networks, aired a piece about the controversy on its version of 60 Minutes, after which more cases emerged. Banolim alleges that Samsung representatives were secretly approaching families and offering to pay them if they withdrew their compensation claims, cut off contact with the group, and maintained public silence. These would not have been akin to lawsuit settlement offers, because there weren’t lawsuits against Samsung; there were only government insurance claims. The company denied making such offers.

Now that Samsung was challenging families directly in court, some decided they would fight the company. On Dec. 15, 2010, a Samsung executive from Giheung returned to Sokcho and visited Hwang at home. “I think we will be able to pay you the money that you will be satisfied with,” the executive told him. “But please don’t tell anyone about this. It places us in a very bad situation.”

Hwang asked, “So you’re saying that you will just pay us, and that’s it?”

“I’m just hoping,” the executive replied, “that you wouldn’t say anything against Samsung. Right now I think there is a very high chance that you won’t be able to get the occupational health insurance anyway.”

Working with KBS, Hwang had secretly recorded the conversation, which the network aired in 2011. Others on the broadcast reported similar offers, including the family of Park Ji-yeon, a 23-year-old woman who died of leukemia in March 2010. Her mother said they got about $330,000 from Samsung, deposited in their bank account on the day of her daughter’s funeral. She also said that company representatives “told us not to meet members of the labor union and to withdraw our lawsuit.” Samsung declined to comment on the recording or payments to Park Ji-yeon.

Hwang’s appeal was consolidated with that of Lee Suk-young’s widower and three other families and heard by a three-judge panel of the Seoul Administrative Court in May 2011. A month later, the presiding judge read out its verdict and opinion in open court. He ruled in favor of Hwang and Lee’s widower and ordered the government compensation fund to pay them.

The panel rejected the appeals of the other three families, detailing case evidence and their reasoning for each worker’s specific job, highlighting chemicals used, potential radiation exposures, ventilation systems, and other processes in place at Giheung and plants where the others worked. (They found other production lines were more modernized and safer than Giheung, especially before 2009, and that, for two male workers, there was a lack of compelling evidence about increased incidences among men.)

Within three weeks of the ruling, Samsung held a press conference with an American consulting firm it had hired, Environ, announcing the consultants had found no statistically significant correlations between workers’ exposures and leukemia. KCOMWEL officials appealed the court’s order awarding benefits to the families of the two women.

Banolim has about 40 cases pending today, either before KCOMWEL or in court, and the eyes of Koreans are on them more than ever. Even before this new attention, the worker’s compensation board had started easing its resistance, awarding benefits in a couple of high-profile cases. Late last year the courts did the same for another worker, with judges saying studies at Samsung chip factories were flawed and failed to account fully for health hazards. The government’s appeal of Hwang’s ruling is pending. More than seven years after Yu-mi died, he’s still waiting for a decision.

Samsung says employees are its greatest asset and that its goal is to create “a workplace culture that accepts nothing less than an unwavering and relentless commitment to upholding best practices in process safety management.” It also says it was the first semiconductor maker to develop real-time chemical monitoring, which it implemented in 2007, and that it has improved air quality monitoring in plants. “While we are deeply saddened by the loss of former members of the Samsung family and are concerned about those battling illness, we would like to reiterate that independent research has not found a correlation between employee illness and workplace environment,” the company says. It also says it’s giving financial support to families, but it will not say how much.

Lee Mi-kyung, who has been a member of the South Korean National Assembly for 18 years, has been an ally to Hwang and the other Samsung families. Sitting down between votes at the members’ cafeteria just outside the body’s chamber, she says Samsung has been so influential in politics, the press, and even the law that many of her countrymen call their land “the Republic of Samsung.” She says things are changing as Korean corporate power continues to be checked gradually across society. She mentions the 2008 corruption investigation into Samsung for allegedly maintaining a slush fund to bribe judges, prosecutors, and politicians. Prosecutors said they did not find evidence of bribery, but they charged and convicted Samsung Electronics Chairman Lee Kun-hee with tax evasion. He paid a fine of roughly $100 million and received a suspended prison sentence.

Samsung posted one of the most interesting public statements about Another Promise on one of its Korean blogs. The posting was attributed by the company to a senior executive, Kim Sun-beom, and is the closest thing to an officially sanctioned reaction. Kim says in the post that he was confronted by his own daughter, who was brought to tears when she saw the movie with friends. She had always been proud of her father’s job with Samsung.

“As a father, I understand [Hwang’s] loss, and partially it is the company’s fault that we left him to fight for seven years,” he wrote. “However, a movie is a movie. It is not right to distort the truth.” Having worked at Giheung himself, Kim also wrote, “I know how hard the company and the workers try to provide a safe environment, so I do not doubt the safety of my workplace.”

|

评分

-

2

查看全部评分

-

|