|

|

【中文标题】世界自由2014

【原文标题】FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2014

【登载媒体】自由之家

【原文链接】http://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2014

这份报告得到了史密斯理查德森基金会、莉莉基金会和施洛斯家族的大力支持。

目录:

1,民主领导力的差距

2,当代独裁行为

3,2013年自由轨迹

4,全球综述

各地区民主风向

- 欧亚地区:黑暗一年中些许闪光

- 中东和北非:突尼斯坚持在民主的道路上

- 拉丁美洲和加勒比地区:委内瑞拉岌岌可危

- 亚太区:中国的新领导人和老样子

- 非洲撒哈拉以南地区:前进和倒退并存

- 欧洲和北美:美国一片混乱,土耳其前途未卜

结论:《世界自由2014》

- 独裁的抵抗

- 民主自信的危机

- 独立国家

- 地区和争议地带

民主领导力的差距

2013年即将结束,整个世界从日常俗务中脱身而出,向为自由奋斗终生的巨人纳尔逊•曼德拉致敬。全世界都传来了盛赞曼德拉作为异见者、政治家和慈善家伟大贡献的声音。美国前总统比尔•克林顿直截了当地说曼德拉是“一个拥有不寻常的魅力和同情心的人,对他来说,忘记痛苦、拥抱敌人不仅仅是一种政治策略,更是一种生活方式。”

但是,给予种族隔离之后的南非之父的赞扬往往伴随着一种渴望。很明显,曼德拉职业生涯中最显著的气质——坚持法制和民主、拒绝清算和复仇、认为政治斗争的零和游戏是对独裁制度和民众冲突的一种邀请——在当今世界的政治领袖中,实在太缺乏了。

实际上,在曼德拉最后的日子里,人类的自由遭到了一系列的威胁。描述全球人民政治权力和公民自由的报告《世界自由》,连续八年显示全世界的自由度都在下降。

尽管整体的退步并不十分明显——54个国家自由度降低,40个国家自由度上升,但自由度降低的国家中包括了很多在战略上和经济上取得了伟大成就的国家,他们的政治影响力已经跨越了边界:埃及、土耳其、俄罗斯、乌克兰、阿塞拜疆、哈萨克斯坦、印度尼西亚、泰国、委内瑞拉。这一年,我们还看到越来越多的国家被血腥的内战、残忍的恐怖行动所困扰:中非、南苏丹、阿富汗、索马里、伊拉克、也门、叙利亚。

总之,这一年并没有出现一些倾向于“忘记痛苦、拥抱敌人”的政治领袖。更糟糕的是,那些需要为残酷暴行和镇压行动承担责任的人,不但没有被贴上耻辱的标记,反而得到了一些“铁腕领导”和“政治家风范”的赞扬。

或许最严重的问题出现在埃及,其第一位民主选举总统穆罕默德•穆尔西尽管得到大部分人民的支持,但在一场老式的军事政变之后被赶下台。穆尔西和他的政治团体——穆斯林兄弟会——在短暂的执政期间出现了一些独裁的倾向,但围绕在阿卜杜勒•法塔赫•塞西将军周围的军事武装力量,无情地把穆斯林兄弟会清除出政坛,并且把一些对临时政府至关重要的因素——比如自由的反对力量——边缘化。7月政府转换之后,埃及当局杀害了一千多名抗议者、逮捕了几乎所有的兄弟会领导层、威胁媒体、迫害民间社会团体、破坏法制。新政府还没能有效镇压伊斯兰武装力量的崛起,这导致了针对安全部队的袭击,和对科普特基督教社区的纵火、私刑等暴力行为。

埃及政变之后的领导层在短短6个月之内,就全面推翻了自2011年开始出现的断断续续的民主进程。过渡政府逐渐翻版了被罢黜的强权领导人侯赛因•穆巴拉克的管理模式,甚至还有过之而无不及。与此同时,美国政府拒绝承认政权的转换是一次政变,只是在表面上反对新政府的杀戮和逮捕行为,甚至还称赞军事领导人渴望民主的愿望。其它国家纷纷与塞西政权巩固关系。

在叙利亚,巴沙尔•阿萨德使用用销毁化学武器的方式来转移人们对他残忍暴行的批评,即使在他疯狂地清除异己的过程中,他一直否认拥有化学武器。这远远算不上是阿萨德的军事核心力量,放弃它们也不会消除空袭、炮击平民区,以及封锁食物和人道主义救援的行为。这些暴行造成超过11.5万人死亡、200万难民和500万人无家可归。叙利亚在这份《世界自由》报告中得分最低。

阿萨德并不是唯一一个采取避重就轻、自私自利、装模作样的姿态来转移公众对国内镇压事件关注的领导人。弗拉基米尔•普京所采取的一系列机会主义策略——包括牵线达成叙利亚化学武器协议;为美国前情报部工作人员爱德华•斯诺登提供政治庇护;赦免数名著名的政治犯——足够改变以下这些话题:俄罗斯领导人迫害国内生活窘迫的居民;在索契冬奥会开幕前几个月威胁邻国。

实际上,普京的独裁政权已经让他第15年担任这个国家的最高领导人,2013年出现了一系列令人发指的行为。政府给抗议者和反对派领导人强加虚拟的罪名,判定已故的腐败行为告发人谢尔盖•马格尼茨基有逃税罪行,试图以这种荒谬的方式削弱他的公信力。还宣布“宣扬非传统性关系”为非法,这引发了各地的暴力、失业,以及议会成员和其他公众人物用用暴力语言攻击LGBT。(译者注:女同性恋、男同性恋、双性恋、跨性别者的英文首字母缩写。)

当代的独裁主义

尽管在这一年自由遭受了军阀和内战的压制,但同样重要的是,这种现象是基于一种更加微妙,但极为有效的手段,就是所谓的独裁主义策略。一些领导人全身心地设法削弱反对派,却不彻底清除他们;蔑视法治,却维持着表面光鲜的社会秩序、法制和繁荣。

当代独裁主义策略的核心是攫取作为政治多元化基石的国家机构,其目的不仅仅是要掌控决策和立法机构,还包括媒体、司法、民间组织、经济和国家机器。尽管独裁者依然认为采取欺诈、私划选区、挑选选举委员会成员和其它手段来确保期望的选举结果非常重要,但他们也同样关注,甚至更加重视把控信息渠道、边缘化社会团体批判人士,以及司法程序的话语权。因此在过去五年中,《世界自由》的评分出现了看起来相反的走向。从全球角度来看,政治权力分数稍有提升,公民自由得分明显下降,在言论自由、信仰自由、法治和民间社团权力方面下降得尤其明显。

这种行为产生的现象是,选举在表面上看来是平静的、颇富竞争性的,即使那些当权的独裁者(或准独裁者)利用各种方式来影响选举环境。例如在津巴布韦,2013年的选举比过去几年的选举令人更加容易接受,因为没有出现效忠于总统罗伯特•穆加贝的武装力量发动的大规模暴力行动。尽管观察人士说选举日的程序基本公平,但选举结果在投票几个月之前就受到了政策和非法手段的影响。

过去一年中明显的一个问题是,很多国家都通过掌控媒体和利用合法手段惩罚异见人士来加强对政治信息的管控。

在委内瑞拉,最大的独立电视台Globovision在政府的压力下被卖出,其政治态度和尖锐的声音发生了彻底的变化。在厄瓜多尔,拉斐尔•德尔加多总统在2012年推动立法机构威胁媒体对选举过程的报道,并确保2013年选举期间实施新的法律。在俄罗斯,普京政府已经完全掌控了国家电视台,把一个广受尊重新闻机构俄新社并入媒体集团“今日俄罗斯”,这是出于激进的宣传策略目的。被委任的今日俄罗斯总裁迪米特里•基谢廖夫曾经说,同性恋“应当被禁止捐献血液和精子。如果他们在车祸中死亡,他们的心脏应当就地掩埋或焚毁,不能允许它延续别人的生命。”在乌克兰,维克多•亚努科维奇总统的亲信及其家人掌控了国家主要媒体机构,并监控全国媒体对政治话题的报道。在中国,当局打击外国新闻机构,有意拖延外国记者的签证,因为他们曾经曝光这个国家的人权暴行,并发表有关政治领导人及其家人商业行为的调查报告。在土耳其,当局采取各种手段来掩盖对总理雷杰普•塔伊普•埃尔多安批评的声音,包括监禁记者(土耳其是世界上监禁记者数量最多的国家),强迫独立出版商向政府裙带部门出售股份,威胁媒体让他们的记者闭嘴。

2013年自由的轨迹

与7年来的趋势相同,2013年有40个国家得分上升,但少于得分下降的54个国家。部分得分上升的国家在非洲,包括马里、科特迪瓦、塞内加尔、马达加斯加、卢旺达、多哥、津巴布韦。然而,这些进步大都来源于灾难性的恢复,或者在极低的基础上的改进。一些得分下降的国家包括中非、塞拉利昂、乌干达、南苏丹、冈比亚、坦桑尼亚和赞比亚。在中东,除了埃及和叙利亚,巴林、黎巴嫩和加沙地带情况也在恶化。

《自由世界》过去5年来的政治权力记录显示,非洲撒哈拉以南地区退步最明显,亚太、中东和北美地区的进步最显著,尽管这里曾经受到阿拉伯春天的严重影响。欧亚国家的政治权力得分最低,中东和北美的公民自由度最差。拉丁美洲分数下降幅度最大,尤其是公民自由得分,比如言论和结社自由。

2013年重大的变化和趋势包括:

反LGBT倾向在俄罗斯和非洲极为严重。LGBT权利在很多地区取得了可喜的进展,尤其是在美国,当地的立法机构和一些案件的裁决极大地主张了婚姻权利,还有一些欧洲和拉丁美洲国家。但是这些成绩被其它国家更凶猛的敌意所压倒,最明显的是俄罗斯和非洲部分国家。在喀麦隆,法律禁止“与同性发生性关系”,有人仅仅因为被怀疑是同性恋而被起诉。2013年,喀麦隆艾滋病基金会负责人在雅温得被杀害,他的脖子被扭断、双脚被压碎、面部被铁块烫得一片模糊。在赞比亚,同性恋会遭受牢狱之灾,最高可判刑15年,并且LGBT群众一直在面临迫害,包括逮捕和监禁的威胁。在乌干达,议会通过了一项反LGBT法案(尽管总统约韦里•穆塞韦尼尚未签署),允许对被禁止的性行为进行惩罚,最高可达终身监禁。还会对“宣扬”同性恋和24小时内知情不报的行为进行惩罚,这项法案将影响到医务人员和LGBT活动人士的工作。

南亚的混乱:去年年末,孟加拉国的局势似乎已经失控,当地出现了针对政治反对派的游行、抗议、抵制选举和镇压行动。但是,南亚其它国家的一些进展,让我们看到这个经历了多年的暴力和政治动荡的地区出现了一些希望。巴基斯坦的选举被认为是具有竞争性,且相对真实,两个当选的民权政府之间完成了权力的交接。不丹反对派在第一次赢得议会选举之后,权力和平过渡。马尔代夫也举办了一次基本上自由、公平的总统选举,尽管最高法院多次干涉并拖延投票进程。尼泊尔在重重困难之中,也完成了一次成功的选举。负面的消息来自斯里兰卡,当地佛教组织中的强硬派针对少数民族宗教团体采取暴力行动,而且得到了官方的首肯。

西非从冲突中恢复:马里和科特迪瓦在多次内战之后终于取得了一些令人刮目相看的进展。2012年,马里的自由类别从“自由”变成“不自由”,因为伊斯兰军事武装力量占领了这个国家的北部,军阀推翻了南部的现任政府。但是法国领导的武装力量打退了军阀,民权政府在总统和议会选举之后恢复职能。这些进展让马里在2013年被定义为“部分自由”。科特迪瓦经历了多年的政治了种族动荡,2011年,总统洛朗•巴博拒绝承认他的对手阿拉萨纳•瓦塔拉在大选中获胜,之后爆发了冲突。在巴博投降并被逮捕之后,国家逐渐向民主制度靠拢,尤其在2013年,其公民自由取得了长足的进步。

中欧的仇外:尽管人们极为关注英国、法国、荷兰、奥地利和其它西欧国家甚嚣尘上的反移民和反欧盟局势,但更加仇外的组织都集中在东欧。与希腊的金色黎明组织一样,保加利亚的攻击党牺牲了政治主流性和国家的经济利益获取了自身的优势地位,当今饱受抗议困扰的政府依然依赖其作为立法基石。攻击党伙同一小撮极端民族主义党派,在2013年度 选举中频繁使用种族主义语言,他们现在的目标是叙利亚难民和穆斯林信徒。在匈牙利,尤比克党主要攻击犹太人和罗马人,尽管过去几年来他们的声音逐渐式微,但依然占有议会11%的席位。斯洛伐克民族党在国家立法院中没有席位,但其对罗马人、匈牙利人和LGBT人群的攻击依然在毒害政治环境。

全球综述

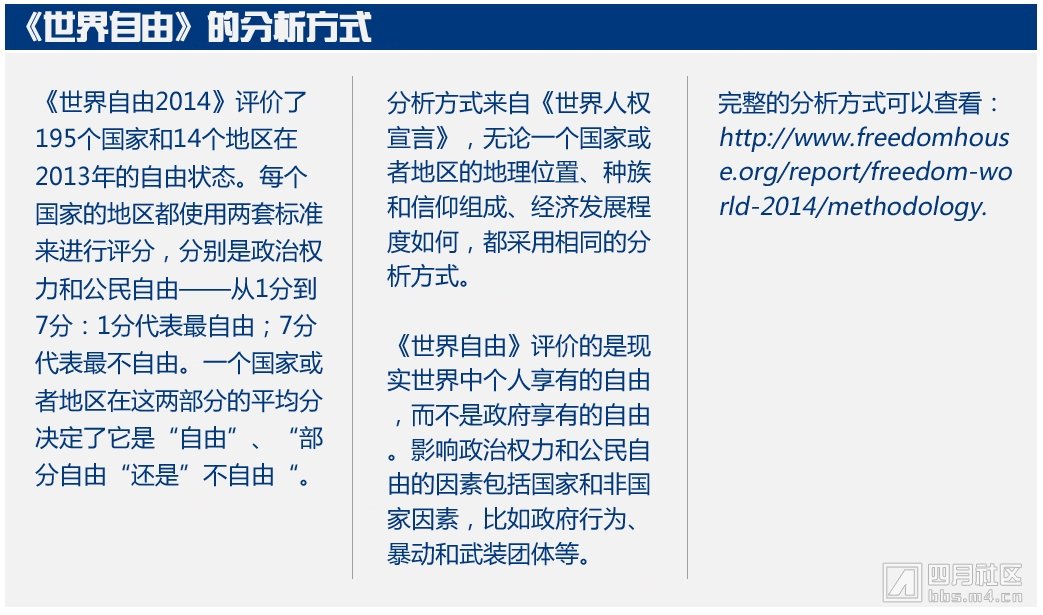

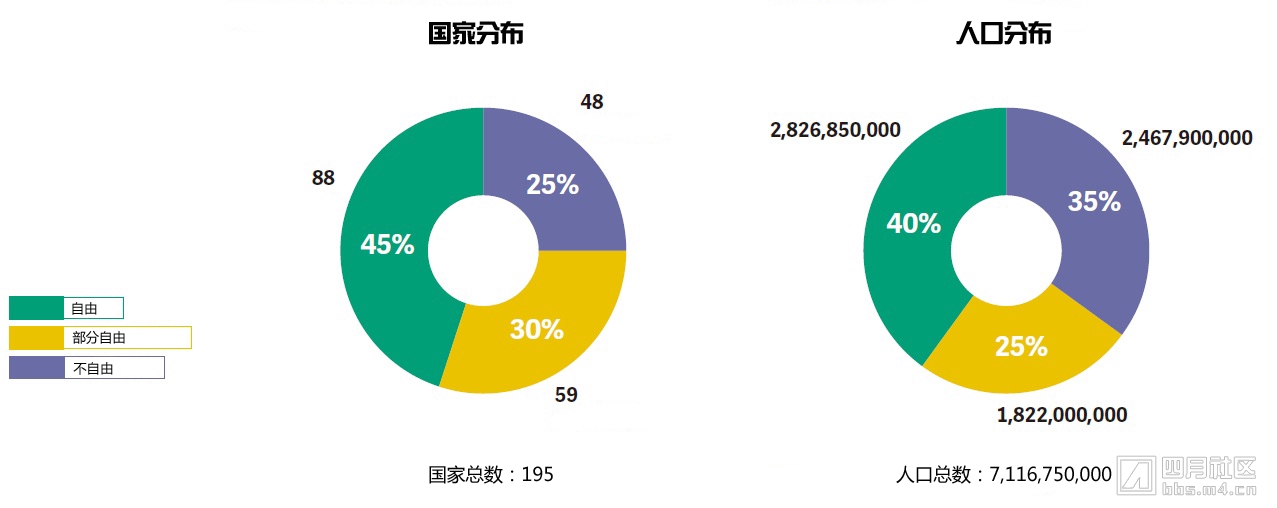

《世界自由》2013年定义为“自由”的国家数量为88,占全部195个政体的45%,覆盖28亿人——占全球总人口数量的40%。

“自由”国家的数量与去年报告相比减少了2个国家。“部分自由”国家的数量为59,占所有国家数量的30%,覆盖18亿人,占全球总人口数量的25%。“部分自由”国家数量比去年的报告增加1个。

共有48个国家被认为是“不自由”,占全世界政体总数的25%,覆盖25亿人口,占全世界人口总数的35%,当然这其中一半以上的人都来自一个国家——中国。“不自由”国家数量比上年度增加1个。

民主选举国家的数量是122个,比2012年增加4个国家——洪都拉斯、肯尼亚、尼泊尔和巴基斯坦。

一个国家从“不自由”上升为“部分自由”——马里。塞拉利昂和印度尼西亚从“自由”下降为“部分自由”,中非和埃及从“部分自由”下降为“不自由”。

各地区民主风向

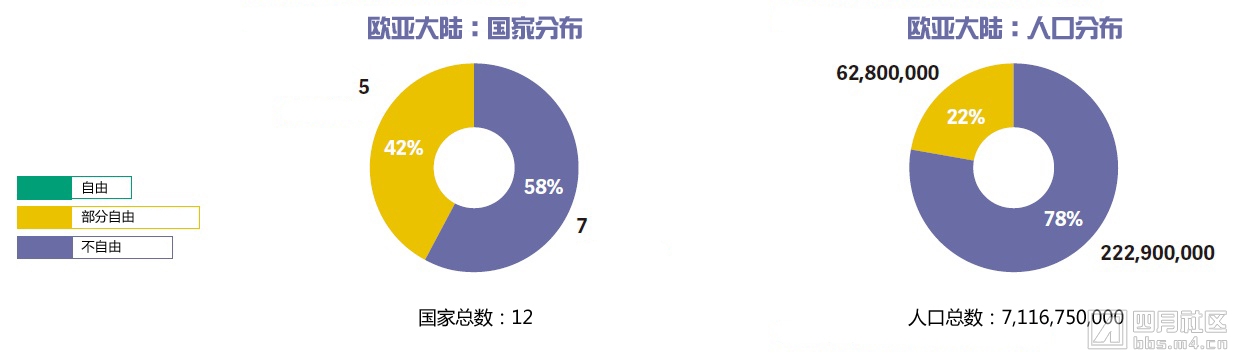

欧亚地区多年来对民主自由的攻击让它的政治权利得分垫底,甚至低于中东国家的平均分。

欧亚大陆:黑暗中些许闪光

2013年欧亚地区发生的事件印证了国际关系中的一句格言:富国犯法不与庶民同罪。这个地区的三个国家得分有所下降,它们是俄罗斯、阿塞拜疆和哈萨克斯坦,它们分数下降的趋势已经持续了十多年。但是,它们蕴藏着富饶的石油和天然气,因此得以不受民主政府的谴责。实际上,俄罗斯即将在下个月举办冬季奥运会,而哈萨克斯坦和阿塞拜疆都主办过各类国际赛事、文化活动和外交聚会。

多年来持续对民主自由的践踏,让大部分欧亚国家在政治权利方面的得分低于其它国家,现在甚至低于中东国家的得分。三个欧亚地区国家——白俄罗斯、土库曼斯坦和乌兹别克斯坦——被自由之家列为世界上最专制的国家。

2013年标志性的事件是俄罗斯使用恐吓手段——尤其是惩罚性贸易限制——来挫败邻国与欧盟的暧昧关系。威胁、恐吓,加上许以小利,足够让亚美尼亚撤回与欧盟结合的计划,转而加入俄罗斯领导的海关贸易协定。在处理乌克兰问题时,俄罗斯首先威胁采取经济报复手段,之后又提供了大笔贷款和能源供给,来说服维克多•亚努科维奇总统放弃欧盟的协定。亚努科维奇在承诺签订协议之后几个月改变了主意,导致基辅出现了大规模的抗议活动,乌克兰人要求这个国家走上欧盟和民主的道路。

格鲁吉亚和摩尔多瓦在欧亚大陆的排名中最靠前,它们顶住俄罗斯的压力,加入的欧盟的协议。在格鲁吉亚,一场被广泛认为是公平和诚信的总统选举标志着他们在民主的道路上前进了一大步。

重要的收获和损失

阿塞拜疆的公民自由得分从5分下降到6分,原因是一年来政府持续侵犯公民的财产权,政府还在总统大选前打击反对派和民权组织。

哈萨克斯坦也在走下坡路,其2011年制定的严格限制宗教行为的法律被不折不扣地执行,甚至有反恐警察冲入私人家庭的聚会。

俄罗斯分数下降的主要原因是2013年针对弱势群体的两次镇压行动。通过禁止“宣扬非传统性关系”的法律打击LGBT群体,以及通过任意监禁高加索、中亚和东亚移民的方式压制移民工人。这两项行动都加深了人们对这些群体的敌意。

乌克兰得分下降的原因是,总统维克多•亚努科维奇放弃欧盟协议转而接受俄罗斯的财政援助,这个决定并未咨询公众的意见,并且违背了大部分乌克兰人的意愿。参与争论的媒体和记者遭到暴力袭击。

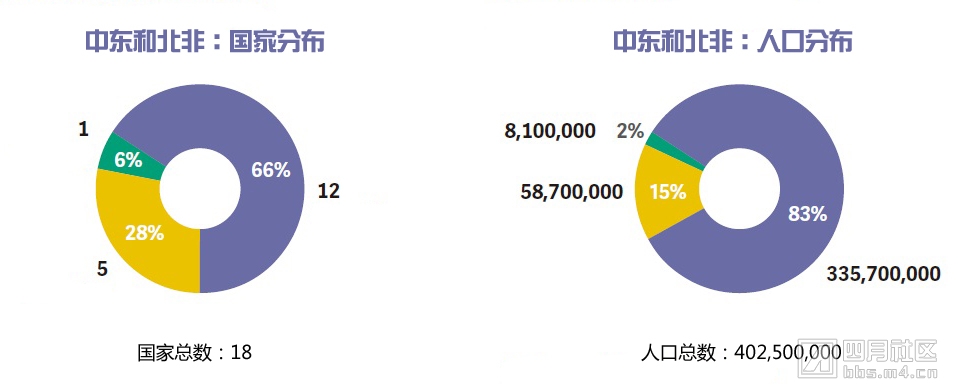

中东和北非:突尼斯坚持在民主的道路上

突尼斯在经历了两次引人关注的暗杀神职领导人和执政的伊斯兰联合组织与反对派几个月的对峙之后,在2013年再一次通过双方的妥协和缓和继续前进。伊斯兰政府同意下台,为一个中性的过渡政府让路,直到2014年新宪法下举办的选举完成。这项协议对于一个在2011年开始阿拉伯春天的国家来说,是一个伟大的进步,让阿拉伯世界依然存在着真正、稳定的民主的希望。

海湾君主制国家的情况不那么乐观,他们竭尽全力阻挠民主改革,比如巴林新出台的限制反对派的政策。

重要的收获和损失

埃及的政治权利得分从5分下降到6分,其政体自由度也从“部分自由”变为“不自由”。主要原因是合法选举的总统穆罕默德•穆尔西在7月被推翻;暴力打击伊斯兰政治组织和民权团体;军队在政治中扮演越来越重要的角色。

突尼斯的公民自由得分从4分上升到3分,主要原因是提升了学术自由度;建立新的工会;放宽旅行限制。

伊拉克的政治权利得分从6分上升到5分,原因是政治改组和4到6月份期间反对派在地方选举中的行为。

加沙地带的政治权利得分从6分下降到7分,原因是2006届巴勒斯坦立法委员会在2010年期满之后,一直未能举行新的选举。

巴林的得分呈下降趋势,原因是新的法令禁止政治团体与外国政府和资助签订合同,以及政府解散伊斯兰学者委员会的举动。

黎巴嫩的得分也在下降,原因是与叙利亚的冲突导致政局瘫痪,新的选举法无法通过,国家大选被推迟到2014年底。

叙利亚得分下降的主要原因是,过去一年里人民生活条件的恶化;破坏教堂以及绑架牧师;在某些领域采取伊斯兰教法的方式进行限制;对女性施加暴力,包括把强奸作为战争的一种方式。

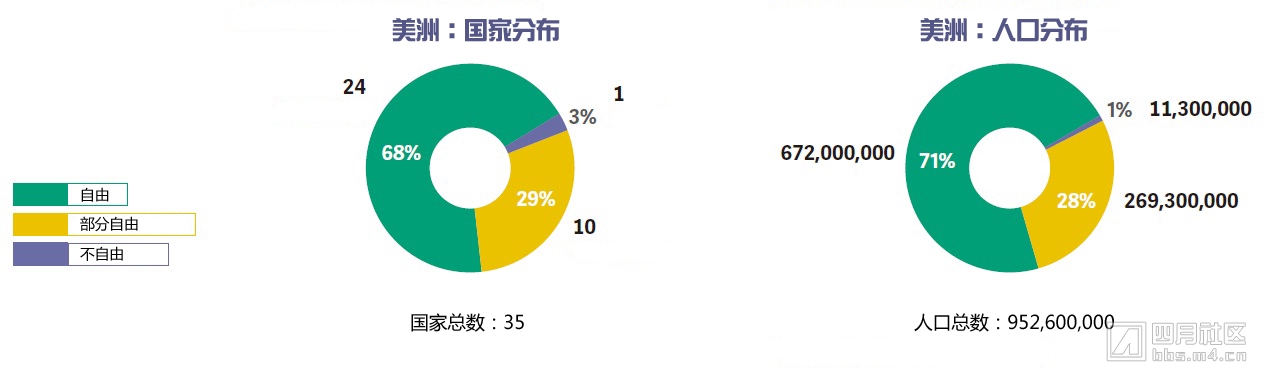

拉丁美洲和加勒比地区:委内瑞拉岌岌可危

委内瑞拉总统雨果•查韦斯在3月份去世,让很多人期望他的继任者或许会缓和独裁政体,与政治反对派寻求共同点。但是新总统尼古拉斯•马杜罗采取倒行逆施的做法。他想尽办法削弱反对派的力量,重新核查国家政策,谴责反对派领导人(和美国政府)的权力失控和无能。他还进一步弱化独立媒体机构的力量,威胁民权组织,在地方选举前派遣安全部队到商场监管商品价格。很多分析人士在去年年末警告,委内瑞拉如果想要避免经济和社会危急,必须进行彻底的政策改革。

正面的消息来自洪都拉斯,观察人士认为大选基本上是公平和富有竞争性的。尽管在2009年罢黜总统曼努埃尔•塞拉亚的政变之后的大选标志着一种进步(塞拉亚的妻子是2013年总统选举的候选人),但洪都拉斯人依然面临着贫穷和犯罪率上升的威胁。

智利和乌拉圭领导着南美洲的民主进程。乌拉圭采取了一些重要的改革措施,包括立法支持同性婚姻。智利举办了一次成功的选举,让前总统米歇尔•巴切莱特有了第二个任期。

尽管古巴依然被《自由世界》划定为世界上最强权的国家之一,但它也取得了些许进步,它放宽了护照申请的限制,并鼓励私有经济体的发展。

重要的收获和损失

尼加拉瓜政治权利的得分从5分上升到4分,公民自由得分从4分上升到3分,原因主要是宪法改革协商会议带来的正面影响、反腐败的进步、透明的政治环境、女性权利的改善,以及与拐卖人口现象斗争的进展。

多米尼加的公民自由得分从2分下降到3分,原因是立宪法院剥夺了数万名海地后裔多米尼加人的公民身份。

巴拿马的政治权利得分从1分下降到2分,原因是当局拒绝调查总统里卡多•马蒂内利和其他官员的腐败问题,以及恶语攻击报道政府腐败的记者。

古巴在各方面有稍许改进,因为它逐步减少政府的监控行为;允许民间和互联网塔伦政治问题;鼓励出境旅行和自治。

巴西的得分有所下降,因为若干政府部门都有腐败的传闻,说他们贩卖护照和其它官方文件,以及执法部门的不作为。

圣塞茨和尼维斯得分下降,因为政府拒绝审议反对派立法机构在2012年12月提交的一份不信任动议。

委内瑞拉得分下降,主要原因是政府有选择性地执行法律和规定来打击反对派,并削弱他们对政府权力的制约作用。

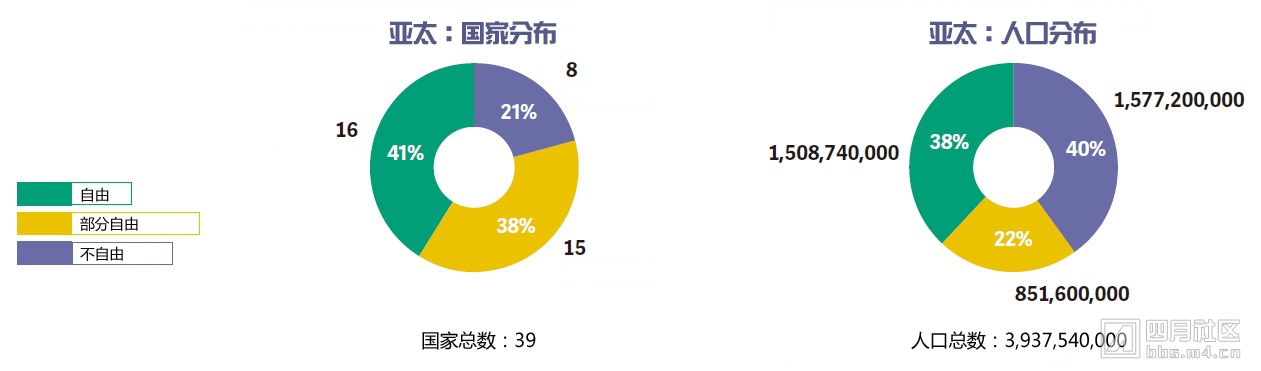

亚太区:中国的新领导人和老样子

尽管官方发布豪言壮语要打击腐败、提升法治、欢迎来自社会各界的声音,但习主席领导下的新中国共产党要比其前任更加不能容忍异见者。知识分子在2013年初呼吁党遵循宪法、减少监控,当局的回应是开展一系列强化意识形态监控的运动。新的司法原则扩大了网络言论、自首和“自我批评”犯罪化的范围,似乎毛时代的精神又回到了电视屏幕上。警方逮捕了数十名与“新公民运动”相关的活动人士,这个组织主张社会改革,包括政府官员公开资产。

我们甚至无法找到中国潜在的进步机会。尽管当局已经开始着手关闭这个国家臭名昭著的“劳改”营,但他们转而采取延长刑期和其它手段,包括行政命令或凌驾法律之上监禁、惩罚人权活动人士、反腐败活动者、上访者和宗教信徒。尽管政府宣布要增加可以生育两个孩子的家庭数量,但这项缺乏人性的法令和维护长久以来独生子女的严苛执法力度依然存在。

仅有的亮点是高层异见者召集广大民众在面对重重阻碍的同时,依然行使他们的权力、挑战司法不公。公众的抗议、互联网运动、记者曝光和人权组织在2013年也取得了一些成就,包括平反冤案。尽管如此,中国公民了解重大信息、揭露腐败、参与政治和社会问题讨论的能力,在互联网监控、打击社交媒体著名评论人和草根监控的大环境下,依然极为弱小。

重要的收获和损失

印度尼西亚的公民自由得分从3分下降到4分,其分类从“自由”下降到“不自由”。主要原因是它通过一项法律,限制非政府组织的活动,强化官方监控,要求各类组织支持这个国家的“建国五项原则”——包括其赤裸裸的一神论内容。

不丹的政治权利得分从4分上升到3分,原因是政府的透明度有所提升,以及在反对派首次赢得议会选举之后权力的和平交接。它的公民自由得分从5分上升到4分,原因是增加了公开和批判性的政治言论自由,以及反对派有更多的机会举行示威和抗议,并且司法独立性有所提升。

日本的公民自由得分从2分上升到1分,原因是民权组织活动更加频繁,并且对宗教自由的法律限制有所减少。

马尔代夫的政治权利得分从5分上升到4分,原因是2013年11月总统大选基本是自由和公平的,尽管最高法院屡次拖延、干涉选举进程。

巴布亚新几内亚的政治权利得分从4分上升到3分,原因是首相彼得•奥尼尔和他的政府有效地回应了屡禁不止的官员腐败问题,并成功起诉了数名前任和现任政府高官。

汤加的政治权利得分从3分上升到2分,原因是在首相病重期间有条不紊地依照宪法程序治国,以及反对派更有效地让掌控政治高层的贵族对选民负责。

韩国的政治权利得分从1分下降到2分,原因是高层的腐败丑闻以及滥用职权,包括国家情报部门干涉政治事务。

巴基斯坦的得分有所上升,原因是在一场基本自由和平等的选举之后,两个民权政府之间的权力顺利交接。

阿富汗的得分有所下降,原因是在北约撤军之后,这个国家的安全状局势显著恶化,导致了越来越多针对政府部门雇员和女性的暴力事件。

孟加拉国的得分有所下降,原因是对网络博客写手的骚扰和攻击;通过信息与通信技术法案限定性修正案,以及在抗议战争法庭的一份裁决时数十名抗议者的死亡。

马来西亚的得分有所下降,原因是猖獗的选举舞弊行为和制度性的障碍阻挠反对派掌权。最高法院判决禁止非穆斯林使用“安拉”代指“上帝”,以及LGBT团体面临越来越多的敌意和偏见。

斯里兰卡的得分有所下降,原因是佛教强硬派加强对基督教和穆斯林少数民族群体的攻击,包括这些人举办宗教活动的财产和场地,而且经常有官方在背后支持。

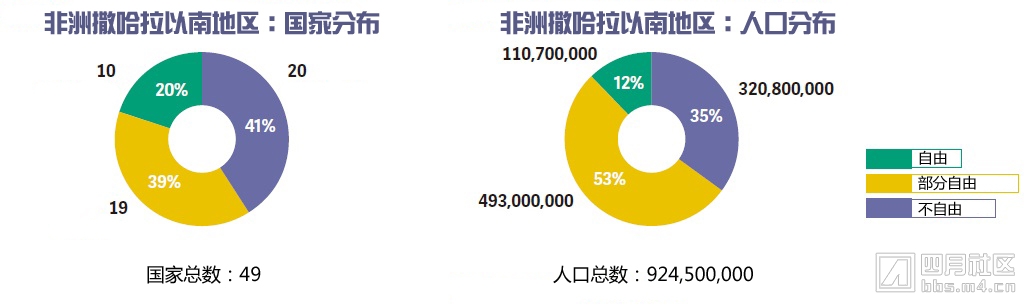

非洲撒哈拉以南地区:前进和倒退并存

在过去十多年的时间里,非洲是世界上最混乱的地区,这里聚集了众多的军阀和战乱。但近几年的历史中还出现过用凭借武力上台的政权让位给选举产生的政党。2013年,这样的现象出现在马里、马达加斯加和科特迪瓦,这些国家都逐渐从军阀和内战中恢复过来。去年还有一些存在独裁记录的国家取得了稍许进步,包括卢旺达、汤加和津巴布韦。与此同时,赞比亚和塞拉利昂的状况在恶化,它们未能实施有效的改革开放政策。

重要的收获和损失

马里的政治权利得分从7分上升到5分,公民自由得分从5分上升到4分,分类也从“不自由”变为“部分自由”。主要原因是他们击败了伊斯兰反叛组织;改善了北部的安全状态;成功举办了总统和立法院选举;大幅度削弱军方在政治中的话语权。

中非的政治权利得分从5分下降到7分,公民自由权利得分从5分下降到7分,分类也从“部分自由”变为“不自由”。主要原因是塞雷卡叛军流放了现任总统和立法机构、废除宪法、犯罪团伙和雇佣军的暴力行为,以及穆斯林与基督教团体之间的冲突。

塞拉利昂的政治权利得分从2分下降到3分,其分类从“自由”变成“不自由”。主要原因是银行家、警察和政府官员的高层腐败,以及长期以来的财务状况异常,导致采掘业透明度组织拒绝接纳这个国家。

科特迪瓦的公民自由得分从5分上升到4分,原因是这个国家进一步创造言论、集会、结社和少数民族自由的环境,以及新政府管理下稳定的政治环境。

马达加斯加的政治权利得分从6分上升到5分,原因是其和平的总统和议会选举被国际观察人士认为是自由和公平的。

卢旺达的公民自由得分从6分上升到5分,原因是社交媒体上出现了越来越多的评论,以及有关保罗•卡加梅总统任期的讨论。

塞内加尔的公民自由得分从3分上升到2分,原因是总统马基•塞勒在2012年执政之后改善了媒体环境了集会的自由。

汤加的政治权利得分从5分上升到4分,原因是立法委全局的成功。它的确出现过一些错误,但被国际观察人士认为总体是公平的,而且没有引发暴力。

津巴布韦的政治权利得分从6分上升到5分,原因是政府在2013年大选期间减少了对反对派政党的骚扰和暴力行为。

南苏丹的公民自由得分从5分下降到6分,原因是12月份愈演愈烈的武装冲突和针对少数民族的大规模杀戮,起因是执政党内部无法容忍异见者和逮捕政治犯的行动。

乌干达政治权利得分从5分下降到6分,主要原因是持续不断地骚扰、逮捕著名反对派领导人;通过公共秩序管理法案进一步限制反对派和民权团体活动;以及执政的全国抵抗运动组织内部选举的不二人选。

贝宁的得分有所下降,主要原因是执政党设法巩固权利。尽管法官宣布起诉无效,但他们依然持续监禁所谓的破坏分子,并且把法官软禁,从政治角度禁止示威和抗议活动。

冈比亚的得分有所下降,原因是对公民自由的进一步限制,包括修改信息通讯法案和犯罪行为法案,目的是限制公开和自由的言论,以及在互联网咖啡厅禁止使用Skype和语音通讯软件。

坦桑尼亚的得分有所下降,原因是武装部队、暴徒和治安团体实施了越来越多的暴力行为,并且都是针对弱势群体,包括女性、白化病环蛇、LGBT成员和接触HIV的高危人群。

赞比亚的得分有所下降,主要原因是执政党持续压迫和骚扰政治反对派,包括动用公共秩序法案,从而削弱了他们取悦公众和参与递补选举的能力。

欧洲和北美:美国一片混乱,土耳其前途未卜

美国政府在2013年经历了一个世纪未曾出现的政府危急。巴拉克•奥巴马总统的政府与国会的共和党反对派长久以来的对峙,在为期两个星期的联邦政府停摆中达到了顶峰。

最终,共和党让步,预算协议终于通过,但是在更重要的问题上双方远未达成一致意见。例如共和党极力阻挠奥巴马大规模修改移民法案的提议,这项法案有机会为非法移民提供合法的身份。

美国政府承诺将加快速度关闭古巴关塔那摩湾的军事监狱设施,有数十名恐怖分子嫌犯自2001年之后未经审判被羁押在那里。然而,2013年之后几名关押犯被释放,到年底为止,仍有150多人被关押。

美国政府还因为国家安全局窃听和数据收集行为饱受本土和外国政府的批评。情报探员的行为,包括收集美国公民和外国亲密盟友的通讯元数据的行为,被爱德华•斯诺登曝光。这位国家安全局的前外包商因为害怕被捕而逃往香港,后来进入俄罗斯,得到政治庇护。

美国成立了一个总统特别委员会,在泄密事件之后来调查国家安全局的行为,最终认定这样的行为并未违反宪法,但建议情报政策和程序进行一系列的变化。检方在调查国家安全局泄密事件时,获取了美联社记者的通话记录,这个行为也遭到广泛的攻击。

欧洲在2013年的重要事件是围绕土耳其埃尔多安政府的危机。埃尔多安在执政初期广受称赞——这份报告也给予了认可,他开启了延期多年的民主改革。之后,改革的步伐似乎陷入停顿。最近,主要的民主机构都面临巨大的压力,基本的公民自由权利纷纷退步。

在“深政”审判中,数百名著名的土耳其人士被控阴谋推翻政府,人们对法治和司法公正产生了巨大的疑问。再加上政府在面临针对埃尔多安盟友的腐败指控时,长期以来设法清除执法官员和检举人。同样麻烦的还有总理针对媒体批判声音的镇压行为,几年前一个与欧盟密切合作的政府,今天变成了反对新闻自由的坏蛋。

埃尔多安的独裁倾向在另一件事情上也得到了展示。抗议者在伊斯坦布尔的一个公园中反对政府的一项计划,独裁政府的报复行为包括打击抗议者、收容他们的企业以及在互联网上发表评论的网友。总理及其幕僚越来越多地把这个国家面临的困境归因于国际阴谋集团的策划。

重要的收获和损失

意大利的政治权利得分从2分上升到1分,原因是议会选举被认为基本上是自由和公平的,以及反腐败政策的实施。

土耳其的得分有所下降,原因是政府对伊斯坦布尔和其它城市抗议者的残酷镇压,并在政治层面打击私有企业,强迫其遵守政府的意愿。

结论:第41期《世界自由》

世界人民的自由在1975年达到最低点,占全世界25%的40个独立国家是“自由”的,占41%的65个国家是“不自由”的。

今年是《世界自由》的第41期。调查采取学术研究方式整理政策数据,目的是将这份采用最严格标准的报告作为衡量全球自由程度的工具。这份报告可以用来警告政策制定者和媒体有关民主的进展和退步,以及自由社会所面临的威胁。

这份报告中包含了一些世界自由状态的隐忧,甚至惊醒。在冷战之后,我们第一次看到民主似乎在退步,全球的民主政权陷入犹豫和彷徨的泥潭。与此相比,中国和苏联这两个共产主义巨人均紧紧把握住社会的控制权。共产主义世界最近的一次改革尝试是1968年的布拉格之春,但被军队镇压,东欧国家不认为革命是一个选择。亚洲、非洲、拉丁美洲和中东都被强权、白人专政、军阀和君主所掌控。甚至在民主理念根深蒂固的西欧也出现了独裁者——希腊、西班牙和葡萄牙。

世界人民的自由在1975年达到最低点,占全世界25%的40个独立国家是“自由”的,占41%的65个国家是“不自由”的。从历史的角度来看,民主世界被局限在西欧、北美和其它几个零星地区。目前的状态让我们对未来没有太大的信心。

但是在之后的25年里,自由经历了人类历史上前所未有的进步。欧洲独裁政府向民主转化,拉丁美洲的军政让位于民政,韩国、台湾和其它亚洲国家纷纷进行政治改革。接下来,共产主义世界揭开了面纱。首先是东欧国家,然后是苏联。苏联共产主义的解体——以及马克思政治体系的灭亡——产生了连锁效应。非洲、拉丁美洲和亚洲的精英不再认为右倾的独裁政体是遏制共产主义的必要手段。

到2000年,“自由”的国家数量上升到86,占45%,“不自由”的国家数量下降到48,占25%。90年代末的巴尔干战争让非洲也掀起了一阵民主热潮,剩下中东是世界上唯一一个没有被塞缪尔•亨廷顿所谓的“第三次民主浪潮”触及的地区。

从那以后,世界的自由陷入停滞和倒退之间的状态。另一方面,过去十年中走向民主的国家基本上没有回到独裁的老路上。欧洲的后共产主义国家一直保持比较高的政治权利和公民自由度,部分原因是欧盟强加给成员国的民主标准。拉丁美洲存在一些问题,尤其是委内瑞拉,但这个地区也经历了历史上最长时间的民主稳定期。

但是,民主的前进遇到了来自三个方面的最大阻挠——中国、欧亚地区和中东。

独裁的抵抗

90年代期间,中国的经济奇迹蓄势待发,很多人预测它很快将进化成一个更加自由,或者一个民主的体制。即使短期内的结果不像华盛顿和布鲁塞尔所理解的那种民主状态,那么它至少也是一个不那么具有压制性、更加容忍批评和更加法治的社会。但是,中国共产党形成了一套相当复杂的执政和惩罚机制,目的是巩固一党政权、阻止异见者,同时又让中国的经济一飞冲天。

苏联解体之后,有人期望新独立的一些国家——也包括俄罗斯——或许会选择民主,放弃共产主义时代的独裁体制。但是除了一些外围的特例,大部分欧亚国家依然维持,或者回到了各种形态的专制中。

整个地区的政治反对派都被监禁、流放或者边缘化,媒体遭到监控,公共财富被执政精英和他们在商界的朋友们掠夺。

中东似乎尤其对自由免疫,直到阿拉伯春天。但是突尼斯、埃及和巴林突然爆发的抗议行动,以及为推翻利比亚和叙利亚独裁政府而出现的武装冲突,遇到了民主政府的忧虑,而不是欢迎。它们的独裁政权毫不担忧,对阿拉伯世界核心地带的民主迹象表现出彻底的敌意。运动之后幸存下来的独裁者和君主努力清除当地的民主人士,继续支持压制、反革命和极端主义行为。

尽管当今世界独裁政权的官方意识形态各异,但它们的领导人明显为达成共同目标而共进退。他们仔细研究其它独裁政府如何被推翻,并琢磨如何避免相同的命运。在某种程度上,独裁政府这种非正式的俱乐部在联合国和其它国际组织中共同采取行动来保护自身的利益,颠覆国际人权标准,设法阻止针对盟友的行动。更令人担忧的是,他们联合起来支持世界上最残暴的政权。叙利亚的现象最明显,俄罗斯、中国、伊朗和委内瑞拉纷纷为阿萨德政权提供外交支持、贷款、燃料,或者直接的军事援助。

民主自信的危机

早期,美国及其盟友承担起世界上政治格局变化的重任。他们乐观而又自信地提供了物质资源和外交力量,让天平向自由运动方向倾斜,同时争取新的民主制度。在这个过程中,很多民间组织也扮演了重要的角色。北美和欧洲贸易联盟让波兰的团结运动在重压之下得以生存;跨国的知识分子团体在捷克斯洛伐克天鹅绒革命中瓦茨拉夫•哈维尔身后集结;全世界的活动人士团结起来推翻了南非的种族隔离制度。

如果说波兰和南非是自由结盟形成的原因,那么今天的导火索就应该是中东。尽管有埃及的军阀和阿萨德的复活倾向,改变的力量已经出现,人们第一次喊出了自治、思想自由和结束压迫的口号。

不幸的是,美国政府未能认识到历史正在重现。我们的确遭遇了挫折,民主的确并非百分之百正确,残酷的地缘政治的确有时与民主变革的目的相冲突,但真正的危险在于政策制定者会落入失败主义循环的圈套,眼睁睁看着出现的问题而束手无策。阿拉伯世界明显在发生变化,问题在于自由是否最终会占据上风,还是说中东会再次陷入新形势残暴统治的魔爪。如果有机会回顾历史,我们会发现,几十年来的独裁统治并未造成就对民主的渴求,而是导致了制度的弱化和目前的极端主义因素。

原因并不复杂。当今的独裁者用他们的自信力和决断力征服了不少人,但进一步的分析会发现,他们花费了太多的时间来阻止变化。俄罗斯和中国的领导人都试图营造一种高层次的意识形态,为他们的统治正名,那就是“传统的”俄罗斯价值观和一种新毛泽东爱国主义思想。与其说是自信,这更像是不合逻辑的产物。

值得一提的是那些冒着极大危险参与埃及、突尼斯和巴林革命的人,他们并没有向“中国梦”唱赞歌,也没有向弗拉基米尔•普京求助。美国或许不是中东地区最受欢迎的国家,但是对民主的渴望——自由的选举、言论自由、反对军政——深藏在阿拉伯世界起义人民的心底。同样的诉求也可以在任何一个专制国家的街道上被听到,包括俄罗斯和中国。

民主世界正在经历一个自我反省的过程,就像自由之家在70年代第一次发布《世界自由》报告一样。一旦它征服了自身的信任危机,美国开始推动世界其它地区的民主化进程,甚至那里的人们还不懂自治为何物。同样的形势即将出现,一些民主国家——包括很多欧洲国家——会竭尽全力扮演建设性的角色。但是如果没有美国领导的决断力,我们在未来只能扼腕叹息失去一个绝佳的机会,而不是庆祝自由思想伟大的突破。

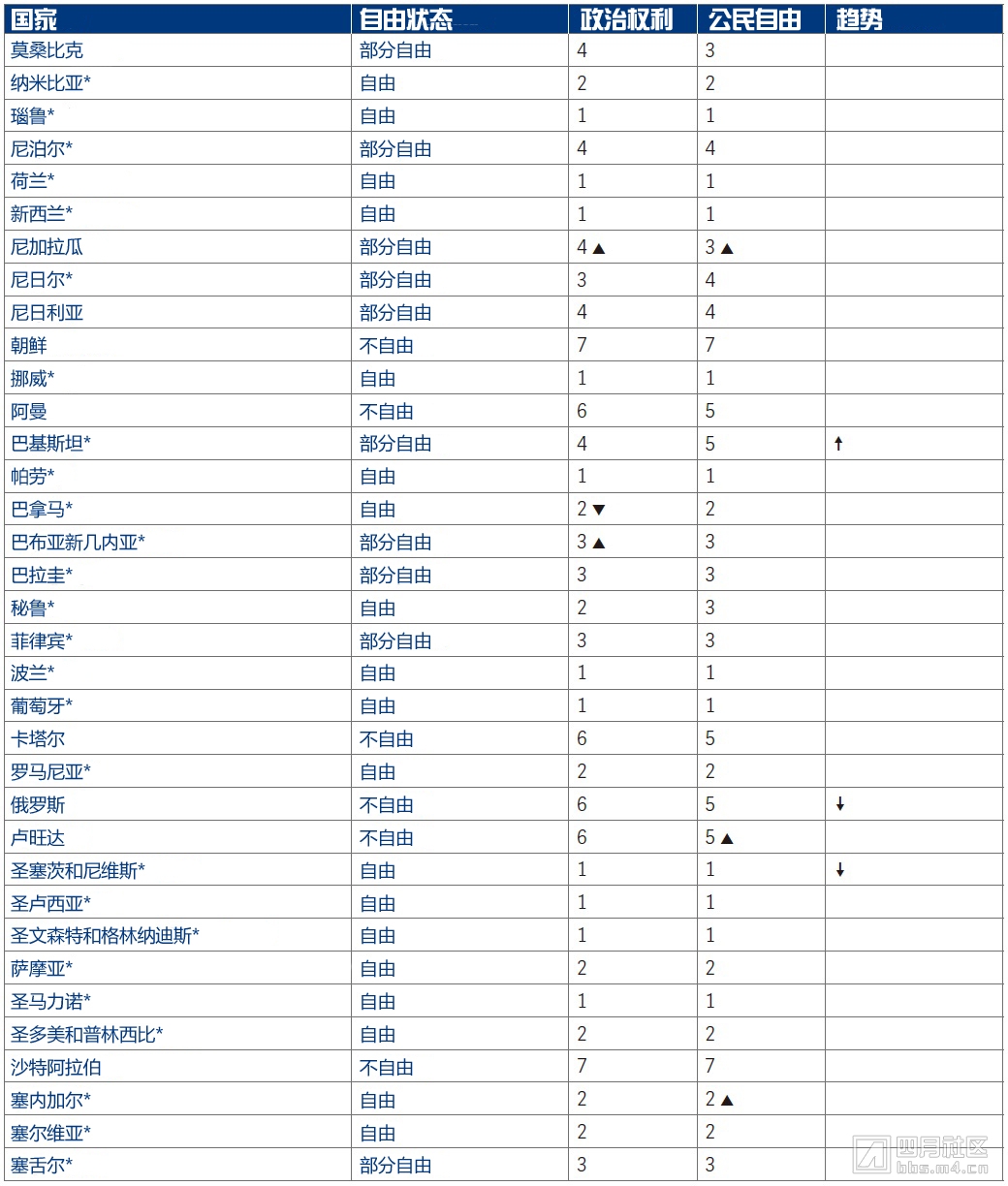

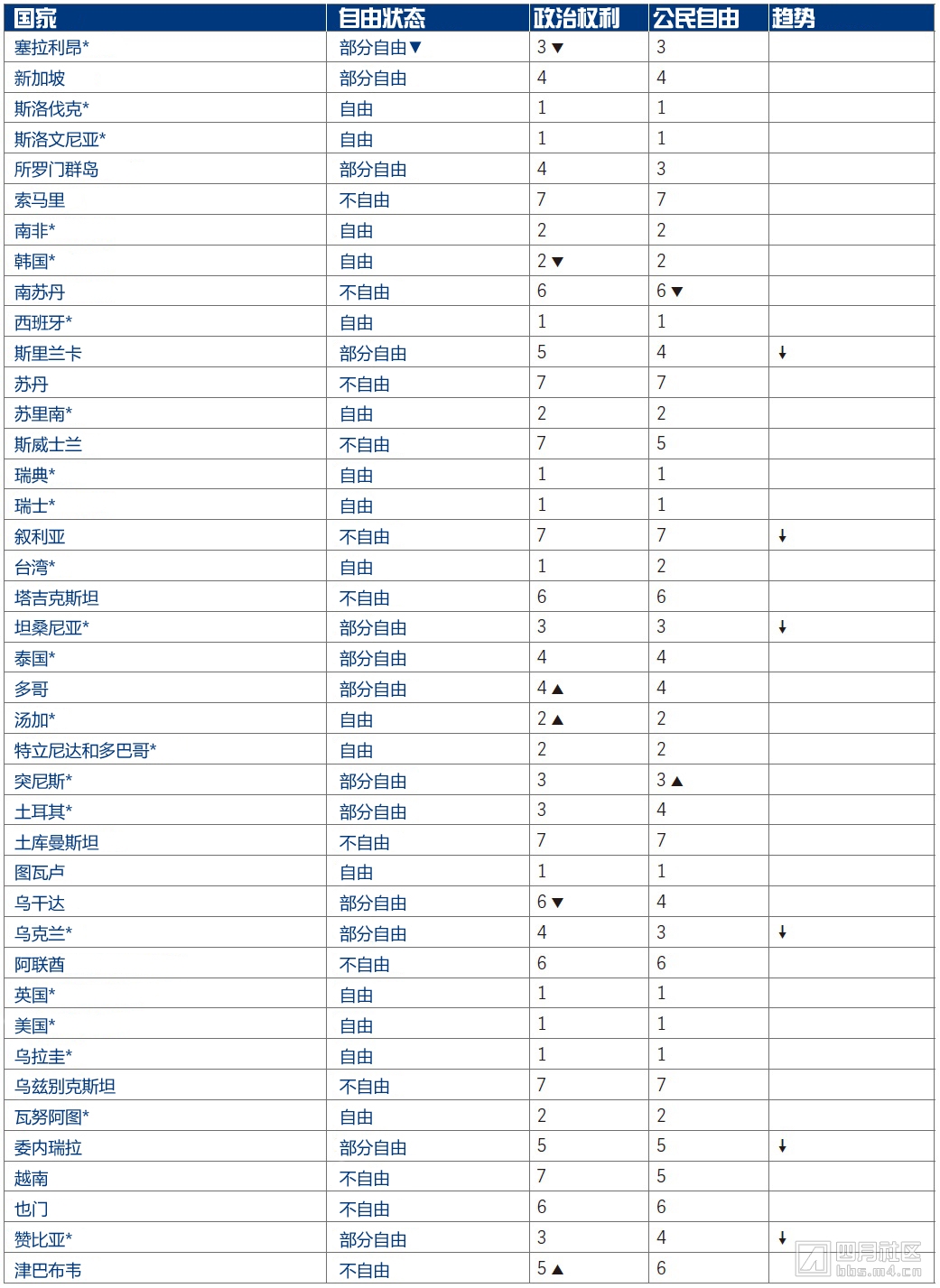

独立的国家

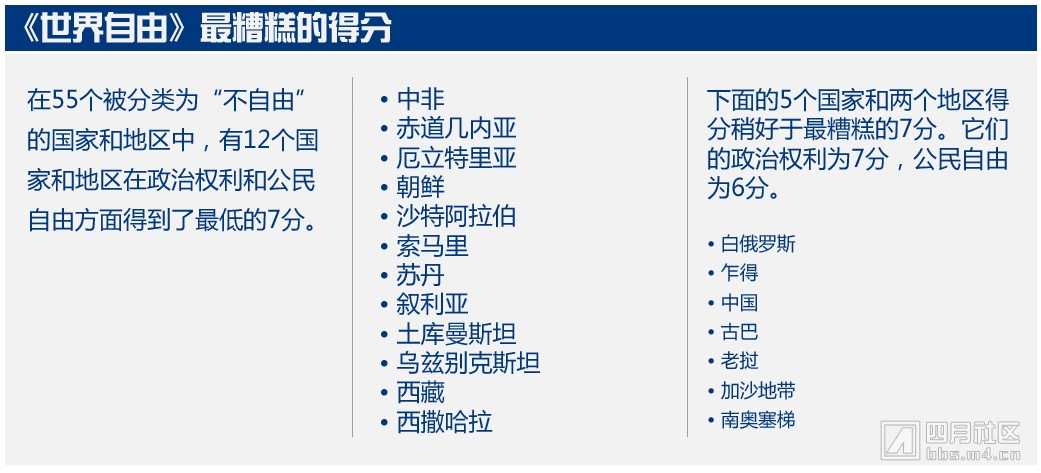

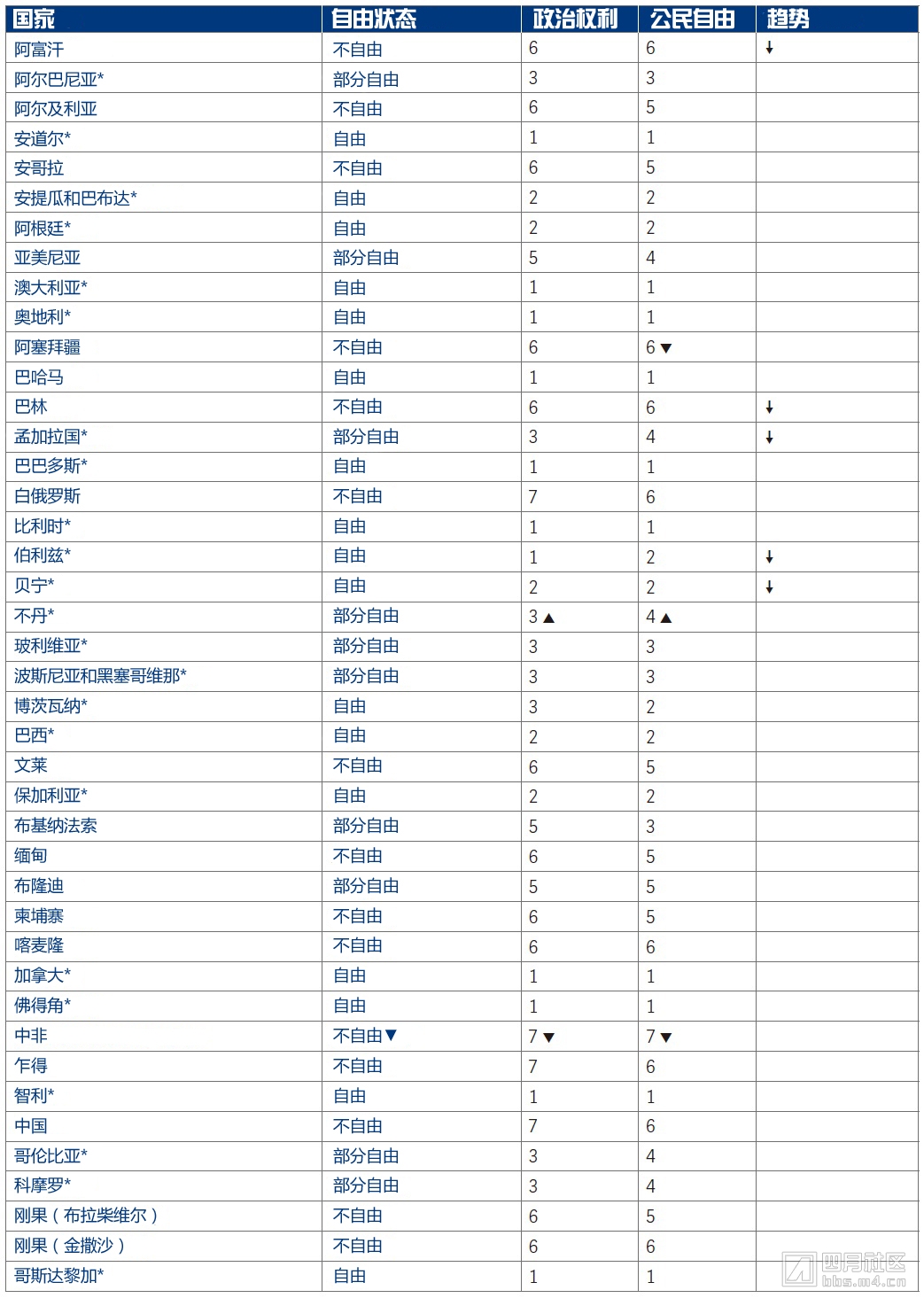

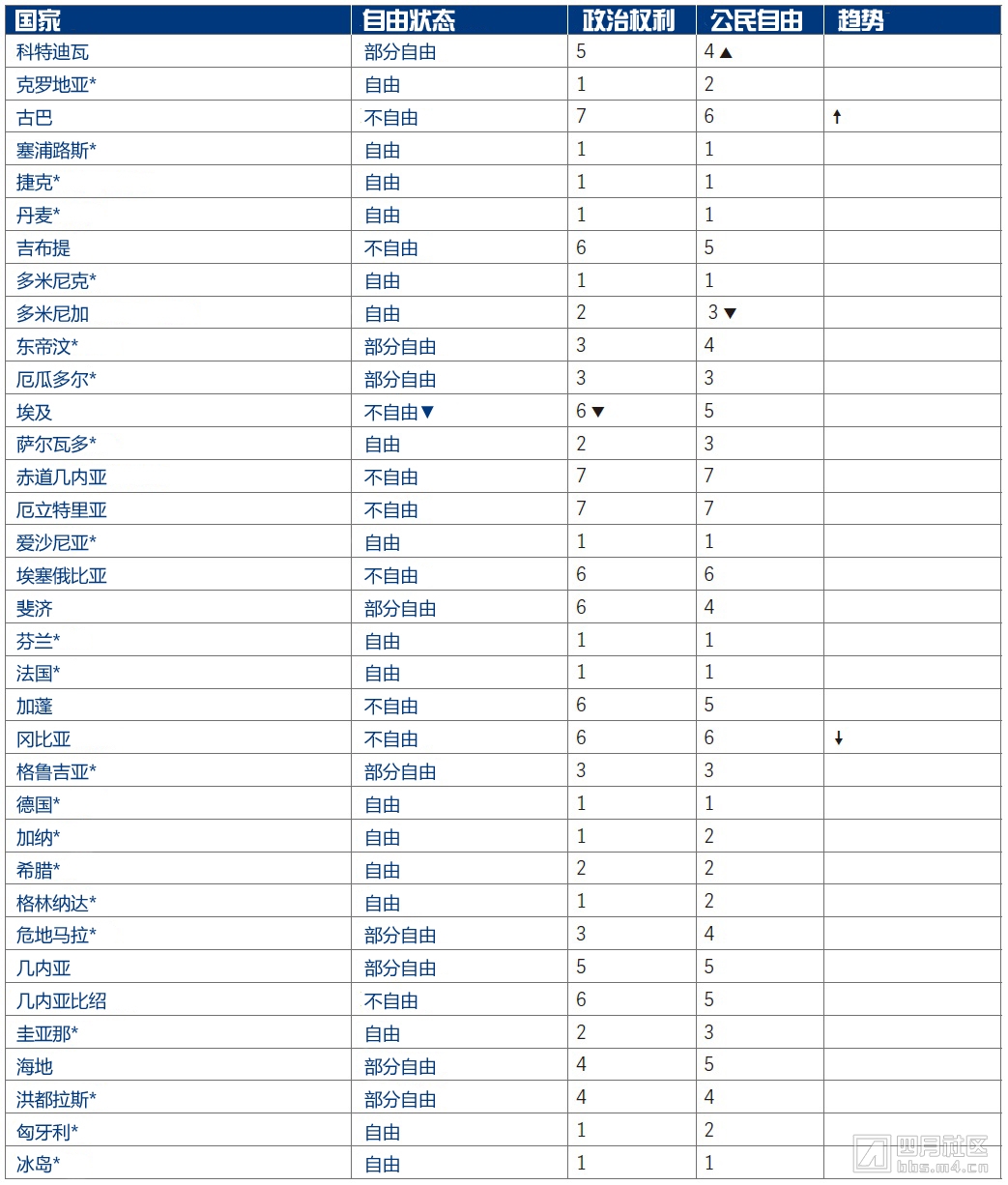

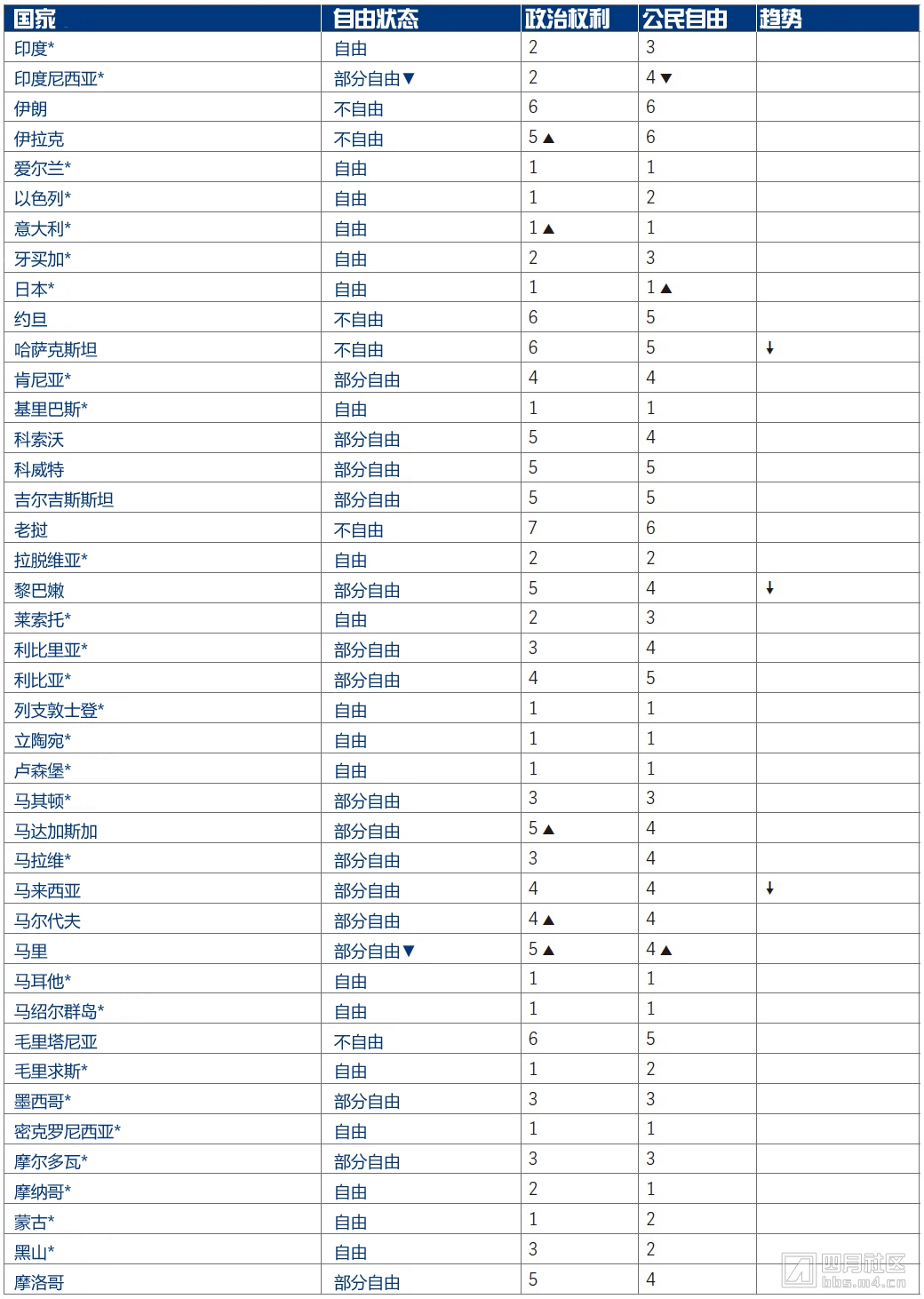

1代表最自由,7代表最不自由。

▲和▼代表与上一次调查相比情况是有所改善还是有所恶化。

↑和↓代表正面和负面的变化趋势,但这样的趋势尚不足以改变政治权利和公民自由的得分。

*表示这个国家有选举自由。

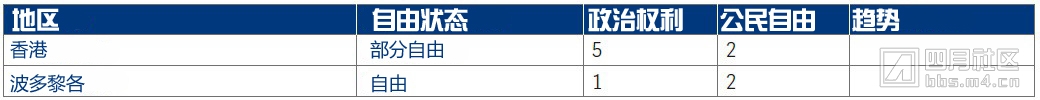

相关地区

争议地区

当代的独裁者基于一种更加微妙,但极为有效的手段,就是所谓的独裁主义策略。他们全身心地设法削弱反对派,却不彻底清除他们;蔑视法治,却维持着表面光鲜的社会秩序、法制和繁荣。

原文:

This report was made possible by the generous support of the Smith Richardson Foundation,the Lilly Endowment, and the Schloss Family.

The Democratic Leadership Gap

Modern Authoritarianism in Action

Freedom’s Trajectory in 2013

Global Findings

Regional Trends

Eurasia: Few glimmers in a dark year

Middle East and North Africa: Tunisia perseveres on the march to democracy

Latin America and Caribbean: Venezuela on the brink

Asia-Pacific: New leadership, little change in China

Sub-Saharan Africa: A pattern of gains and reversals

Europe and North America: Dysfunction in the United States, an uncertain future for Turkey

Conclusion: Freedom in the World at 41

The Authoritarian Resistance

The Democracies’ Crisis of Confidence

Independent Countries

Related and Disputed Territories

The Democratic Leadership Gap

by Arch Puddington, Vice President for Research

As the year 2013 neared its end, the world stepped back from ordinary affairs of state to signal its deep respect for a true giant of the freedom struggle, Nelson Mandela. Praise for Mandela’s qualities as dissident, statesman, and humanitarian came from every part of the globe and from people of all stations in life. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton tellingly described Mandela as “a man of uncommon grace and compassion, for whom abandoning bitterness and embracing adversaries was not just a political strategy but a way of life.”

But the praise bestowed on the father of post-apartheid South Africa was often delivered with more than a note of wistfulness. For it was apparent to many that the defining convictions of Mandela’s career—commitment to the rule of law and democratic choice, rejection of score settling and vengeance seeking, recognition that regarding politics as a zero-sum game was an invitation to authoritarianism and civil strife—are in decidedly short supply among today’s roster of political leaders.

Indeed, the final year of Mandela’s life was marked by a disturbing series of setbacks to freedom. For the eighth consecutive year, Freedom in the World, the report on the condition of global political rights and civil liberties issued annually by Freedom House, showed a decline in freedom around the world.

While the overall level of regression was not severe— 54 countries registered declines, as opposed to 40 where gains took place—the countries experiencing setbacks included a worrying number of strategically or economically significant states whose political trajectories influence developments well beyond their borders: Egypt, Turkey, Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Indonesia, Thailand, Venezuela. The year was also notable for the growing list of countries beset by murderous civil wars or relentless terrorist campaigns: Central African Republic, South Sudan,Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Yemen, Syria.

In short, this was not a year distinguished by political leaders who showed much inclination toward “abandoning bitterness and embracing adversaries.” To make matters worse, some of those who bear responsibility for serious atrocities and acts of repression were not only spared the world’s opprobrium, but in some cases drew admiring comments for their “strong leadership” and “statesmanship.”

Perhaps the most troubling developments took place in Egypt, whose first competitively elected president, Mohamed Morsi, was removed from office in an old-fashioned military coup, albeit backed by the acclamation of many citizens. While Morsi and his political movement, the Muslim Brotherhood, had exhibited authoritarian tendencies during their short period of leadership, the military and allied forces arrayed around General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi have moved ruthlessly to both eliminate the Brotherhood from political life and marginalize the liberal secular opposition and other elements of society that are critical of the interim government. Since the July takeover, the authorities have killed well over a thousand demonstrators, arrested practically the entire Brotherhood leadership, coopted or intimidated the media, persecuted civil society organizations, and undermined the rule of law. The government also failed to quell a rise in Islamist militancy, including attacks on security forces and sectarian violence in the form of arson and lynchings aimed at the Coptic Christian community.

In just six months, Egypt’s post-coup leadership systematically reversed a democratic transition that had made halting progress since 2011. The interim authorities are coming to resemble, and in some areas exceed, the regime of deposed strongman Hosni Mubarak. Meanwhile, the U.S. government has refused to label the seizure of power a coup, issued little more than pro forma objections to the authorities’ killings and arrests, and on occasion praised the conduct and supposed democratic aspirations of the military leadership. Other countries have moved to solidify relations with al-Sisi.

In Syria, the regime of Bashar al-Assad managed to deflect criticism of its criminal brutality by agreeing to the removal of chemical weapons whose existence it had long denied, even as its ruthless drive to wipe out the opposition intensified. Chemical arms were never central to Assad’s military strategy, and their abandonment has had no effect on aerial bombing and artillery barrages, often directed at urban civilian targets, or the use of blockades on food and humanitarian aid as a war tactic. These and other abuses have combined to produce over 115,000 deaths, two million refugees, and five million internally displaced persons. Syria now earns the lowest scores in the entire Freedom in the World report.

Assad is not the only leader to distract the world from domestic repression through superficial, selfserving gestures of reasonableness. A series of opportunistic maneuvers by Vladimir Putin—brokering the Syrian chemical weapons agreement, granting political asylum to former American intelligence contractor Edward Snowden, and approving pardons for several high-profile political prisoners—were enough to change the subject from the Russian leader’s persecution of vulnerable populations at home and campaign of intimidation against neighboring countries just months before the opening of the Winter Olympics in Sochi.

In fact, the authoritarian regime created by Putin, now in his 15th year as the country’s paramount leader, committed a string of fresh outrages during 2013. The authorities brought spurious criminal charges against protesters and opposition leaders, convicted a dead man—corruption whistleblower Sergey Magnitsky—of tax evasion in an absurd bid to discredit him, and adopted a measure that outlawed “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations,” triggering violence, job dismissals, and venomous verbal attacks against LGBT people by parliamentarians and other public figures.

Modern Authoritarianism in Action

While freedom suffered from coups and civil wars during the year, an equally significant phenomenon was the reliance on more subtle, but ultimately more effective, techniques by those who practice what is known as modern authoritarianism. Such leaders devote full-time attention to the challenge of crippling the opposition without annihilating it, and flouting the rule of law while maintaining a plausible veneer of order, legitimacy, and prosperity.

Central to the modern authoritarian strategy is the capture of institutions that undergird political pluralism. The goal is to dominate not only the executive and legislative branches, but also the media, the judiciary, civil society, the economy, and the security forces. While authoritarians still consider it imperative to ensure favorable electoral outcomes through a certain amount of fraud, gerrymandering, handpicking of election commissions, and other such rigging techniques, they give equal or even more importance to control of the information landscape, the marginalization of civil society critics, and effective command of the judiciary. Hence the seemingly contradictory

trends in Freedom in the World scores over the past five years: Globally, political rights scores have actually improved slightly, while civil liberties scores have notably declined, with the most serious regression in the categories of freedom of expression and belief, rule of law, and associational rights.

A result of this approach is that elections are more likely to be peaceful and at least superficially competitive, even as authoritarian (or aspiring authoritarian) incumbents use multiple tools to manipulate the electoral environment as needed. In Zimbabwe, for example, the elections of 2013 were less objectionable than in past years, if only due to the absence of widespread violence perpetrated by security forces loyal to President Robert Mugabe. Although observers judged that procedures on election day were relatively fair, the outcome was strongly influenced by policies and abuses meant to tilt the playing field months before the balloting took place.

The past year was notable for an intensification of efforts to control political messages through domination of the media and the use of legal sanctions to punish vocal critics.

In Venezuela, the leading independent television station, Globovision, was neutralized as a critical voice after it was sold under government pressure to business interests that changed its political coverage. In Ecuador, President Rafael Correa, having pushed through legislation in 2012 that threatened to cripple media coverage of elections, ensured that the law was implemented during the balloting in 2013. In Russia, the Putin regime, having gained dominance over the national television sector, folded a respected staterun news agency, RIA Novosti, into a consolidated media entity, Russia Today, that is likely to be more aggressively propagandistic. Among other alarming remarks, designated Russia Today chief Dmitriy Kiselyov has said that gay people “should be banned from donating blood, sperm. And their hearts, in case of the automobile accident, should be buried in the ground or burned as unsuitable for the continuation of life.” In Ukraine, associates of President Viktor Yanukovych and his family have gained control of key media outlets and censored coverage of major political issues. In China, the authorities pressured foreign news organizations by delaying or withholding visas for correspondents who had exposed human rights abuses or whose outlets published investigative reports about the business dealings of political leaders and their families. And in Turkey, a range of tactics have been employed to minimize criticism of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. They include jailing reporters (Turkey leads the world in the number of imprisoned journalists), pressuring independent publishers to sell their holdings to government cronies, and threatening media owners with reprisals if critical journalists are not silenced.

Freedom’s Trajectory in 2013

As in the seven preceding years, the number of countries exhibiting gains for 2013, 40, lagged behind the number with declines, 54. Several of the countries experiencing gains were in Africa, including Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Madagascar, Rwanda, Togo, and Zimbabwe. However, some of these improvements represented fragile recoveries from devastating crises or slight increases from quite low baselines. There were also important declines on the continent, including in Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, Uganda, South Sudan, the Gambia, Tanzania, and Zambia. In the Middle East, in addition to Egypt and Syria, deterioration was recorded for Bahrain, Lebanon, and the territory of Gaza.

An assessment of the Freedom in the World political rights indicators over the past five years shows the most pronounced declines in sub-Saharan Africa and the greatest gains in the Asia-Pacific and Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regions, though there has been significant rollback of the improvements associated with the Arab Spring. Eurasia registered the lowest scores for political rights, while MENA had the worst scores for civil liberties categories. Latin America saw declines on most indicators, especially in the civil liberties categories, such as freedom of expression and freedom of association.

Major developments and trends in 2013 included:

Anti-LGBT Measures in Russia, Africa: There were some positive developments for the rights of LGBT people, especially in the United States, where state-level legislative action and court decisions significantly expanded marriage rights, and in several European and Latin American countries. But these gains were overshadowed by hostile measures adopted or more vigorously enforced in other countries, most notably Russia and parts of Africa. In Cameroon, the penal code forbids “sexual relations with a person of the same sex,” but people are prosecuted on the mere suspicion of being gay. During the year the executive director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS was found murdered in Yaoundé, his neck broken, feet smashed, and face burned with an iron. In Zambia, same-sex relations are punishable by prison sentences of up to 15 years, and members of the LGBT community have faced increased persecution, including arrests and trials. In Uganda, an anti-LGBT bill passed by the parliament (though not signed by President Yoweri Museveni at year’s end) allows penalties of up to life in prison for banned sexual activity. It would also punish individuals for the “promotion” of homosexuality and for not reporting violations within 24 hours, a provision likely to affect health workers and advocates for LGBT rights.

Volatility in South Asia: At year’s end, events in Bangladesh seemed ready to spin out of control, with demonstrations, strikes, an election boycott, and repressive measures against the political opposition. Yet developments elsewhere in South Asia suggested some reason for hope in a subregion that has experienced years of violence and political instability. Pakistan held elections that were deemed competitive and reasonably honest, allowing the first successful transfer of power between two elected, civilian governments. Bhutan benefited from a peaceful rotation of power after the opposition won parliamentary elections for the first time. The Maldives held a largely free and fair presidential election despite several delays and repeated interference by the Supreme Court, and there were also successful elections amid many obstacles in Nepal. On a less positive note, Sri Lanka experienced a decline due to violence directed at religious minorities by hard-line Buddhist groups, often with official sanction.

Rebounding from Conflict in West Africa: Both Mali and Côte d’Ivoire registered impressive improvements after suffering through periods of lethal internal conflict. In 2012, Mali’s designation had plummeted from Free to Not Free after Islamist militants gained control of the country’s northern regions and a military coup overthrew the elected government in the south. But French-led forces succeeded in driving back the militants, and civilian government was restored through presidential and parliamentary elections. These developments enabled Mali to achieve a Partly Free designation for 2013. Côte d’Ivoire’s years of political and ethnic strife were punctuated by a 2011 conflict that erupted after President Laurent Gbagbo refused to accept the election victory of his rival, Alassane Ouattara. Since Gbagbo’s surrender and arrest, the country has made steady progress toward the consolidation of democratic institutions, especially during 2013, with major improvements in the civil liberties environment.

Xenophobia in Central Europe: While attention has focused on the rise of anti-immigration and Euroskeptic parties in Britain, France, the Netherlands, Austria, and other Western European countries, more virulently xenophobic groups have been at work to the east. Like Golden Dawn in Greece, Bulgaria’s Ataka party has gained strength at the expense of the political mainstream as the country’s economy has suffered, and the current protest-battered government relies on it for a legislative majority. Ataka and smaller ultranationalist parties regularly used racist rhetoric in their electoral campaigns in 2013, and they have recently targeted refugees from Syria and Muslim citizens. In Hungary, Jobbik focuses its attacks on Jews and Roma, and although its popularity has softened over the past several years, it still holds 11 percent of the seats in parliament. The Slovak National Party (SNS) currently has no seats in that country’s legislature, but its slurs against Roma, Hungarians, and LGBT people continue to poison the political atmosphere.

Global Findings

The number of countries designated by Freedom in the World as Free in 2013 stood at 88, representing 45 percent of the world’s 195 polities and slightly more than 2.8 billion people—or 40 percent of the global population.

The number of Free countries decreased by two from the previous year’s report. The number of countries qualifying as Partly Free stood at 59, or 30 percent of all countries assessed, and they

were home to just over 1.8 billion people, or 25 percent of the world’s total. The number of Partly Free countries increased by one from the previous year.

A total of 48 countries were deemed Not Free, representing 25 percent of the world’s polities. The number of people living under Not Free conditions stood at nearly 2.5 billion people, or 35 percent of the global population, though it is important to note that more than half of this number lives in just one country: China. The number of Not Free countries increased by one from 2012.

The number of electoral democracies stood at 122, four more than in 2012. The four countries that achieved electoral democracy status were Honduras, Kenya, Nepal, and Pakistan.

One country rose from Not Free to Partly Free: Mali. Sierra Leone and Indonesia dropped from Free to Partly Free, while the Central African Republic and Egypt fell from Partly Free to Not Free.

Regional Trends

The year-by-year assault on democratic freedoms through much of Eurasia has brought it to the point where its scores on political rights indicators are lower than those of any other region, now slightly worse than the aggregate scores for Middle Eastern countries.

Eurasia: Few glimmers in a dark year

Developments in Eurasia during 2013 proved the adage that in global affairs there is one standard for countries with energy wealth and another, more rigorous standard for everyone else. Three states in the subregion that suffered declines for the year—Russia, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan—are locked in a downward spiral that has been ongoing for over a decade, but they are rich in natural gas and oil, and thus have largely escaped the condemnation of democratic governments. Russia, in fact, is looking forward to hosting the Winter Olympics next month, while Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have played host to various other international competitions, cultural festivals, and diplomatic gatherings.

The year-by-year assault on democratic freedoms through much of Eurasia has brought it to the point where its scores on political rights indicators are lower than those of any other region, now slightly worse than the aggregate scores for Middle Eastern countries. Three Eurasian states, Belarus, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, are included in Freedom House’s list of the world’s most repressive countries.

A signal development during 2013 was Russia’s use of bullying tactics—especially punitive trade restrictions—to discourage neighboring countries from initialing Association Agreements with the European Union. Threats, table thumping, and the promise of tenuous rewards were enough to persuade Armenia to scuttle its plans for closer EU integration and join a Russian-led customs union instead. In dealing with Ukraine, Russia first employed threats of economic retaliation and then offered a major loan and energy- price deal to convince President Viktor Yanukovych to abandon the EU agreement. Yanukovych’s actions came after months of pledges to sign the pact, and the betrayal triggered ongoing, mammoth street protests in Kyiv by Ukrainians demanding a European and democratic orientation for their country.

Georgia and Moldova, which boast Eurasia’s best rankings on the Freedom in the World scale, did initial their EU agreements despite concerted Russian pressure. In Georgia, a presidential election that was widely regarded as fair and honest marked a further step toward the consolidation of democracy.

Notable gains or declines:

Azerbaijan’s civil liberties rating declined from 5 to 6 due to ongoing, blatant property rights violations by the government in a year in which the state also cracked down on the opposition and civil society in advance of presidential elections.

Kazakhstan received a downward trend arrow due to broad extralegal enforcement of its already strict 2011 law on religious activity, with raids by antiterrorism police on gatherings in private homes.

Russia received a downward trend arrow due to increased repression of two vulnerable minority groups in 2013: the LGBT community, through a law prohibiting “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations,” and migrant laborers, through arbitrary detentions targeting those from the Caucasus, Central Asia, and East Asia. Both efforts have fed public hostility against these groups.

Ukraine received a downward trend arrow due to violence against journalists and media manipulation associated with the controversy over President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to forego a European Union agreement and accept a financial assistance package from Russia—a decision made without public consultation and against the wishes of a large portion of the Ukrainian people.

Middle East and North Africa: Tunisia perseveres on the march to democracy

After two high-profile assassinations of secularist leaders and months of deadlock between the ruling Islamist-led coalition and the largely secularist opposition, Tunisia once again found a way forward in 2013 through compromise and moderation on both sides. The Islamist government agreed to step down in favor of a neutral caretaker government that will rule until elections are held under a new constitution in 2014. The agreement was a significant breakthrough for the country that began the Arab Spring of 2011 and remains the best hope for genuine, stable democracy in the Arab world.

Developments were less positive among the Gulf monarchies, whose bitter resistance to democratic reform included fresh restrictions on the opposition in Bahrain.

Notable gains or declines:

Egypt’s political rights rating declined from 5 to 6 and its status declined from Partly Free to Not Free due to the overthrow of elected president Mohamed Morsi in July, violent crackdowns on Islamist political groups and civil society, and the increased role of the military in the political process.

Tunisia’s civil liberties rating improved from 4 to 3 due to gains in academic freedom, the establishment of new labor unions, and the lifting of travel restrictions.

Iraq’s political rights rating improved from 6 to 5 due to an increase in political organizing and activity by opposition parties during provincial elections held in April and June.

The Gaza Strip’s political rights rating declined from 6 to 7 due to the continued failure to hold new elections since the term of the 2006 Palestinian legislature expired in 2010.

Bahrain received a downward trend arrow due to a new ban on unapproved contact between political societies and foreign officials or organizations as well as a government move to dissolve the Islamic Scholars’ Council.

Lebanon received a downward trend arrow due to political paralysis stemming from the Syrian conflict that prevented the passage of a new electoral law and led to the postponement of national elections until late 2014.

Syria received a downward trend arrow due to the worsening conditions for civilians in the past year, the increased targeting of churches for destruction and kidnapping of clergy, the implementation of harsh Sharia-inspired restrictions in some areas, and unchecked violence against women, including the use of rape as a weapon of war.

Latin America and Caribbean: Venezuela on the brink

The death of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez in March triggered hopes that his successors might moderate his authoritarian course and seek common ground with the political opposition. Instead, the new president, Nicolás Maduro, moved in the opposite direction. He took measures to reduce the opposition’s ability to serve as a check on government policy, blamed opposition leaders (and the United States) for power outages and other symptoms of government ineptitude, further weakened the independent media, made threats against civil society organizations, and dispatched security forces to retail outlets to enforce price controls on consumer goods prior to municipal and regional elections. Many analysts warned at year’s end that Venezuela would require a major shift in policy if it is to avoid an economic and social crisis.

A positive note was a national election in Honduras that observers deemed generally fair and competitive. While the vote was an indication of progress toward political normalcy after the 2009 coup that removed President Manuel Zelaya from office (Zelaya’s wife was the runner-up in the 2013 presidential race), Honduras still confronts high rates of poverty and spiraling crime statistics.

Both Chile and Uruguay burnished their images as leading South American democracies. Uruguay adopted several important reform measures, including the legalization of same-sex marriage, while Chile conducted successful elections that returned former president Michelle Bachelet to office for a second term.

Cuba also registered a small step forward due to the easing of visa restrictions and the growth of the private economic sector, though the island remains among the world’s most repressive countries as measured by Freedom in the World.

Notable gains or declines:

Nicaragua’s political rights rating improved from 5 to 4 and its civil liberties rating improved from 4 to 3 due to the positive impact of consultations on proposed constitutional reforms, advances in the corruption and transparency environment, and gradual progress in women’s rights and efforts to combat human trafficking.

The Dominican Republic’s civil liberties rating declined from 2 to 3 due to a decision by the Constitutional Court to retroactively strip the citizenship of tens of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent.

Panama’s political rights rating declined from 1 to 2 due to concerns that authorities were not investigating allegations of corruption against President Ricardo Martinelli and other officials, as well as verbal attacks against, and the withholding of information from, journalists who write about government corruption.

Cuba received an upward trend arrow due to a modest decline in state surveillance, a broadening of political discussion in private and on the internet, and increased access to foreign travel and self-employment.

Belize received a downward trend arrow due to reports of corruption across several government ministries related to the sale of passports and other documents, as well as an inadequate response by law enforcement agencies.

Saint Kitts and Nevis received a downward trend arrow due to the government’s improper efforts to block consideration of a no-confidence motion that had been submitted by opposition legislators in December 2012.

Venezuela received a downward trend arrow due to an increase in the selective enforcement of laws and regulations against the opposition in order to minimize its role as a check on government power.

Asia-Pacific: New leadership, little change in China

Despite official rhetoric about fighting corruption, improving the rule of law, and inviting input from society, the new Chinese Communist Party leadership under President Xi Jinping has proven even more intolerant of dissent than its predecessors. After intellectuals and other members of civil society called in early 2013 for the party to adhere to China’s constitution and reduce censorship, the authorities responded with campaigns to intensify ideological controls. New judicial guidelines expanded the criminalization of online speech, confessions and “self-criticisms” reminiscent of the Mao era reappeared on television screens, and police arrested dozens of activists affiliated with the New Citizens Movement who had advocated reforms including asset disclosures by public officials.

Even potentially positive changes fell short. Although authorities began to close the country’s infamous “reeducation through labor” camps, they increasingly turned to criminal charges with potentially longer sentences and various alternative forms of adminis- trative or extralegal detention to punish human rights defenders, anticorruption activists, petitioners, and religious believers. And despite announced reforms that will increase the number of families permitted to have two children, the intrusive regulations and harsh practices used to enforce the country’s long-standing birth quotas remained in place.

A bright spot was the determination of high-profile dissidents as well as large numbers of ordinary citizens to assert their rights and challenge injustice in the face of heavy obstacles. Public protests, online campaigns, journalistic exposés, and activist networks scored several victories during the year, including the release of individuals from wrongful detention. Nevertheless, the ability of Chinese citizens to share breaking news, uncover corruption, or engage in public debate about political and social issues was hampered by increased internet controls and crackdowns on prominent social-media commentators and grassroots antigraft activists.

Notable gains or declines:

Indonesia’s civil liberties rating declined from 3 to 4 and its status declined from Free to Partly Free due to the adoption of a law that restricts the activities of nongovernmental organizations, increases bureaucratic oversight of such groups, and requires them to support the national ideology of Pancasila—including its explicitly monotheist component.

Bhutan’s political rights rating improved from 4 to 3 due to an increase in government transparency and a peaceful transfer of power after the opposition won parliamentary elections for the first time, and its civil liberties rating improved from 5 to 4 due to an increase in open and critical political speech, the political opposition’s greater ability to hold demonstrations, and the growing independence of the judiciary.

Japan’s civil liberties rating improved from 2 to 1 due to a steady rise in the activity of civil society organizations and an absence of legal restrictions on religious freedom.

The Maldives’ political rights rating improved from 5 to 4 due to the largely free and fair presidential election held in November 2013, despite several delays and repeated interference by the Supreme Court.

Papua New Guinea’s political rights rating improved from 4 to 3 due to efforts by Prime Minister Peter O’Neill and his government to address widespread official abuse and corruption, enabling successful prosecutions of several former and current highranking officials.

Tonga’s political rights rating improved from 3 to 2 due to the orderly implementation of constitutional procedures in response to the prime minister’s incapacitation by illness, and the opposition’s increasing ability to hold politically dominant nobles accountable to the electorate.

South Korea’s political rights rating declined from 1 to 2 due to high-profile scandals involving corruption and abuse of authority, including alleged meddling in political affairs by the National Intelligence Service.

Pakistan received an upward trend arrow due to the successful transfer of power between two elected, civilian governments following voting that was widely deemed free and fair.

Afghanistan received a downward trend arrow due to the deteriorating security environment linked to the drawdown of NATO troops, which resulted in an increase in violence against aid workers and women in public office.

Bangladesh received a downward trend arrow due to increased legal harassment and attacks on bloggers, the passage of restrictive amendments to the Information and Communication Technology Act, and the deaths of dozens of protesters during demonstrations over verdicts by the country’s war crimes tribunal.

Malaysia received a downward trend arrow due to rampant electoral fraud and structural obstacles designed to block the opposition from winning power, a decision by the highest court to forbid non-Muslims from using the term “Allah” to refer to God, and worsening hostility and prejudice faced by the LGBT community.

Sri Lanka received a downward trend arrow due to intensified attacks by hard-line Buddhist groups against the Christian and Muslim minorities, including their properties and places of worship, often with official sanction.

Sub-Saharan Africa: A pattern of gains and reversals

For the past decade or so, Africa has been the most volatile region, suffering from a disproportionate share of the world’s coups and insurgencies. But its recent history also includes a number of instances in which regimes installed by force have given way to elected civilian rule. In 2013, gains were noted in Mali, Madagascar, and Côte d’Ivoire, all of which were recovering from coups and civil conflicts. The past year also featured modest improvements for countries with authoritarian records, including Rwanda, Togo, and Zimbabwe. At the same time, there were declines for Zambia and Sierra Leone, which had been credited with promising reforms or openings in recent years.

Notable gains or declines:

Mali’s political rights rating improved from 7 to 5, its civil liberties rating improved from 5 to 4, and its status improved from Not Free to Partly Free due to the defeat of Islamist rebels, an improved security situation in the north, and successful presidential and legislative elections that significantly reduced the role of the military in politics.

The Central African Republic’s political rights rating declined from 5 to 7, its civil liberties rating declined from 5 to 7, and its status declined from Partly Free to Not Free due to the Séléka rebel group’s ouster of the incumbent president and legislature, the suspension of the constitution, and a general proliferation of violence by criminal bands and militias, spurring clashes between Muslim and Christian communities.

Sierra Leone’s political rights rating declined from 2 to 3 and its status declined from Free to Partly Free due to high-profile corruption allegations against bankers, police officers, and government officials as well as long-standing accounting irregularities that led to the country’s suspension from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Côte d’Ivoire’s civil liberties rating improved from 5 to 4 due to further openings in the environment for freedoms of expression, assembly, and association, as well as for minority groups, as the security situation stabilized under the new government.

Madagascar’s political rights rating improved from 6 to 5 due to the holding of competitive and peaceful presidential and parliamentary elections that were deemed free and fair by international and regional observers.

Rwanda’s civil liberties rating improved from 6 to 5 due to increasing critical commentary on social media, as illustrated by the unhindered online debates regarding Paul Kagame’s presidential tenure.

Senegal’s civil liberties rating improved from 3 to 2 due to improvements in the media environment and for freedom of assembly since President Macky Sall took office in 2012.

Togo’s political rights rating improved from 5 to 4 due to successful elections for the national legislature, which suffered from alleged irregularities but were generally deemed fair by international observers and did not feature serious violence.

Zimbabwe’s political rights rating improved from 6 to 5 due to a decline in harassment and violence against political parties and opposition supporters during the 2013 elections.

South Sudan’s civil liberties rating declined from 5 to 6 due to increased armed conflict and mass killings along ethnic lines, triggered by intolerance for dissent within the ruling party and politically motivated arrests in December.

Uganda’s political rights rating declined from 5 to 6 due to the continued, repeated harassment and arrest of prominent opposition leaders, the passage of the Public Order Management Bill to further restrict opposition and civil society activity, and new evidence of the limited space for alternative voices within the ruling National Resistance Movement.

Benin received a downward trend arrow due to increasing efforts by the executive to consolidate power, as demonstrated by the continued detention of alleged coup plotters despite a judge’s dismissal of their charges, the placement of the judge under house arrest, and politicized bans on a number of planned demonstrations and protests throughout the year.

The Gambia received a downward trend arrow due to worsening restrictions on civil liberties, including amendments to the Information and Communication Act and the Criminal Code Act that further limited open and free private discussion, and a ban on the use of Skype and other voice communication programs in internet cafés.

Tanzania received a downward trend arrow due to an increase in acts of extrajudicial violence by security forces, mob and vigilante violence, and violence against vulnerable groups including women, albinos, members of the LGBT community, and those at high risk of contracting HIV.

Zambia received a downward trend arrow due to the ruling party’s ongoing repression and harassment of the political opposition, including the increased use of the Public Order Act, hindering its ability to operate in general and to campaign in by-elections.

Europe and North America: Dysfunction in the United States, an uncertain future for Turkey

The United States in 2013 endured a level of government gridlock not seen in over a century. The long-running standoff between the administration of President Barack Obama and his Republican Party opponents in Congress culminated in a two-week partial shutdown of the federal government.

Ultimately, the Republicans backed down and a budget agreement was adopted. But little progress was made on a broad set of important issues. For example, Republican resistance played a major role in thwarting Obama’s proposed overhaul of the country’s immigration laws, which would include a path toward citizenship for some undocumented immigrants.

The U.S. government pledged to redouble its efforts to close down the military prison facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where scores of terrorism suspects have been held without trial since 2001. However, only a handful of detainees were released and placed in other countries during 2013; at year’s end there were over 150 detainees at the facility.

The administration also found itself under criticism from civil libertarians at home and a number of foreign governments for the eavesdropping and data-collection tactics of the National Security Agency (NSA). The intelligence agency’s sprawling activities, including its collection of communications metadata on American citizens and its intrusive monitoring of close foreign allies, was made public through a series of leaks by Edward Snowden, a contractor who had worked for the NSA. Fearing arrest, Snowden fled to Hong Kong and then to Russia, where he was granted asylum.

A special presidential commission set up to review the NSA’s practices after the leaks did not find violations of Americans’ constitutional rights, but it did recommend a series of changes in intelligence policy and procedures. The administration separately came under fire during the year after prosecutors gained access to the telephone records of journalists who worked for the Associated Press as part of an internal investigation into leaked national security information.

Among the most important developments in Europe during 2013 was the escalating crisis surrounding the Erdoğan government in Turkey. In his early years in power, Erdoğan was widely praised—and credited in this report—for introducing overdue democratic reforms. Then came a period in which reform efforts seemed to stall. More recently, key democratic institutions have faced intense pressure, and basic civil liberties have experienced setbacks.

A series of “deep state” trials, in which hundreds of prominent Turks have been charged with alleged conspiracies to overthrow the government, have raised serious questions about the rule of law and selective justice. These concerns have only been compounded by the government’s ongoing purge of law enforcement officials and prosecutors in response to corruption cases recently brought against Erdoğan’s allies. Just as troubling is the prime minister’s campaign against critical voices in the media. A government that several years ago was in serious negotiations on EU membership is notorious today as a major adversary of press freedom.

Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies were on display in his imperious reaction to the year’s protests over a development plan that would eliminate a cherished Istanbul park. Reprisals by the authorities extended to protesters, businesses accused of sheltering them, and social-media users who commented on the events, among others. With increasing frequency, the prime minister and his allies blamed their troubles on supposed plots by international cabals.

Notable gains or declines:

Italy’s political rights rating improved from 2 to 1 due to parliamentary elections that were generally considered to be free and fair as well as progress in the adoption and implementation of anticorruption measures.

Turkey received a downward trend arrow due to the harsh government crackdown on protesters in Istanbul and other cities and increased political pressure on private companies to conform with the ruling party’s agenda.

Conclusion: Freedom in the World at 41

The state of freedom reached its nadir in 1975, when 40 countries, just 25 percent of the world’s independent states, were ranked as Free, compared with 65 countries, or 41 percent, ranked as Not Free.

This year marks the 41st edition of Freedom in the World. From the beginning, the survey used scholarly research to inform the policy debate. It was conceived as an instrument that would employ rigorous methods to measure the state of global freedom, after which the findings would be publicized in order to alert policymakers and the press to democracy’s gains and setbacks, as well as the major threats to free societies.

At the time the report was launched, there was reason for concern, if not alarm, about the condition of world freedom. For the first time since the early years of the Cold War, democracy seemed to be in retreat, and the world’s democratic powers were mired in doubt and confusion. By contrast, the two communist giants, China and the Soviet Union, appeared firmly in control of their societies. The most recent effort at reform in the communist world, the Prague Spring of 1968, had been crushed by military invasion, and the rest of Eastern Europe had digested the message that liberalization was not on the agenda. Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East were dominated by strongmen, white-minority regimes, military juntas, and absolute monarchs. Even Western Europe, where democracy was generally well entrenched, had its dictatorships—in Greece, Spain, and Portugal.

The state of freedom reached its nadir in 1975, when 40 countries, just 25 percent of the world’s independent states, were ranked as Free, compared with 65 countries, or 41 percent, ranked as Not Free. At that point in history, the democratic universe was restricted to Western Europe, North America, and a few other scattered locales, and recent trends gave little cause for optimism about the future.

But for the next quarter-century, the state of freedom experienced a period of progress unprecedented in human history. After the embrace of democracy by the European dictatorships, military governments gave way to civilian rule in Latin America, followed by the beginning of political change in South Korea, Taiwan, and other Asian states. Then came the unraveling of the communist world, first in the East European satellites and then in the Soviet Union itself. The collapse of Soviet communism—and the effective demise of Marxism as a political system—had additional ripple effects, as elites in Africa, Latin America, and Asia could no longer claim that right-wing dictatorships were necessary to forestall the spread of communist totalitarianism.

Thus by 2000, the number of countries designated as Free had surged to 86, or 45 percent of the total, while the number of Not Free states had declined to 48, or 25 percent. With the end of the 1990s Balkan wars and a modest surge of democratic governance in Africa, the Middle East remained the only major part of the world that had been relatively untouched by what Samuel Huntington labeled the third wave of democracy.

Since then, the state of freedom has been situated somewhere between stagnation and decline. On the one hand, few of the countries that moved toward democracy in the previous decades sank back into authoritarian rule. Europe’s postcommunist countries have maintained a high standard of rights and liberties, in part due to the EU’s imposition of democracy criteria for new member states. There have been problems in Latin America—most prominently in Venezuela—but on balance the region has experienced the longest period of stable democracy in its history.

On the other hand, the march of democracy has met with a wall of resistance in three major settings: China, Eurasia, and the Middle East.

The Authoritarian Resistance

During the 1990s, when the foundations for its economic miracle were being set, many predicted that China would rather quickly evolve toward a more liberal and perhaps democratic system. If the immediate results were not democracy as understood in Washington and Brussels, it would at least be a system that was less repressive, more tolerant of criticism, and more subject to the rule of law. Instead, the Chinese Communist Party leadership has developed a complicated apparatus of controls and punishments designed to maintain rigid one-party rule and prevent the expression of dissent, while at the same time enabling China to become a global economic powerhouse.

In the immediate aftermath of the Soviet unraveling, there were also expectations that a number of the new independent states, including Russia, would opt for democracy and reject the authoritarian institutions of communist times. But with a few peripheral exceptions, the bulk of the Eurasian states have remained in or returned to various forms of despotism.

Across the region, the political opposition has been jailed, forced into exile, or made irrelevant; the media have been coopted or censored; and public wealth has been plundered by ruling elites and their cronies in the business community.

The Middle East seemed especially impervious to liberalization until the Arab Spring. Yet the sudden emergence of protest movements in Tunisia, Egypt, and Bahrain, and the armed conflicts arising from similar efforts to overthrow dictatorships in Libya and Syria, were greeted by democratic governments more with apprehension than enthusiasm. Their authoritarian counterparts had no such misgivings, displaying unalloyed hostility toward the prospect of democratic change in the Arab heartland. The region’s surviving dictatorships and monarchies have worked actively to undermine local democrats and give encouragement to the forces of repression, counterrevolution, or extremism.

While the official ideologies of today’s authoritarian powers vary considerably, their leaders clearly form alliances in order to advance common goals. They have studied how other dictatorships were destroyed and are bent on preventing a similar fate for themselves. At one level, a loose-knit club of authoritarians works to protect mutual interests at the United Nations and other international forums, subverting global human rights standards and blocking precedent-setting actions against fellow despots. More disturbingly, they collaborate to prop up some of the world’s most reprehensible regimes. This is most visible at present in Syria, where Russia, China, Iran, and Venezuela have offered diplomatic support, loans, fuel, or direct military aid to the Assad regime.

The Democracies’ Crisis of Confidence

In an earlier period, it was the United States and its allies that were the guarantors of political change in the world. Self-assured and optimistic, they provided the material resources and diplomatic muscle that tipped the balance in favor of freedom movements and struggling new democracies. In this undertaking, a range of private actors also played a critical role. Trade unions

from North America and Europe made it possible for Poland’s Solidarity movement to survive under duress; a transnational alliance of intellectuals mobilized behind Václav Havel during Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution; activists worldwide joined together to press for an end to South African apartheid.

If Poland and South Africa were once the causes that inspired freedom’s allies, today the animating cause is—or should be—the Middle East. Egypt’s coup and Assad’s apparent resurgence notwithstanding, the forces of change have been unleashed, and for the first time popular demands for self-government, freedom of thought, and an end to oppression have been placed squarely on the table.

Unfortunately, the American government has failed to recognize the historic moment that presents itself in the region. It is true that there have been setbacks, that democratic forces have made mistakes, and that rigid geostrategic priorities sometimes conflict with the goals of democratic change. But there is a real danger that policymakers will become locked into a defeatist loop, seeing validation for their inaction in the very problems it produces. The Arab world is clearly in flux, and the question is whether those committed to free societies will prevail or whether the Middle East will fall prey to new forms of repressive rule. Observers who might prefer to turn back the clock should remember that decades of authoritarian misrule, not demands for democracy, led to the institutional weaknesses and extremist elements now in plain view.

The cause is far from lost. While today’s authoritarians impress many with their self-assurance and determination, a closer examination suggests that modern despots devote much of their time to holding actions against popular demands for change. Recently, the leaderships in Russia and China have attempted to develop overarching ideas that would justify their ruling policies. The predictable answers—“traditional” Russian values and a kind of neo-Maoist nationalism—smack more of incoherence than confidence in the future.

It is noteworthy that those who, at considerable personal risk, have joined the struggle for change in Egypt, Tunisia, and Bahrain are not chanting in praise of the “China Dream” or issuing appeals to Vladimir Putin. The United States may not be the most popular country in the Middle East, but desire for the democratic benefits it enjoys—free elections, freedom of expression, and guarantees against police-state predation—lies at the heart of the ongoing uprising in the Arab world. Similar demands can be heard on the streets or are uttered more furtively in virtually every authoritarian state, Russia and China included.

The democratic world was experiencing a period of self-absorption much like today’s when Freedom House launched Freedom in the World during the 1970s. Once it had overcome its crisis of confidence, America helped propel a historic surge of democratization in parts of the world where self-government was almost unknown. A similar era of change could be in the offing, and some democracies—including a number in Europe—have done their best to play a constructive role. But if there is no reassertion of American leadership, we could well find ourselves at some future time deploring lost opportunities rather than celebrating a major breakthrough for freedom.

INDEPENDENT COUNTRIES

PR and CL stand for political rights and civil liberties, respectively; 1 represents the most free and 7 the least free rating.

▲ ▼ up or down indicates an improvement or decline in ratings or status since the last survey.

↑↓up or down indicates a trend of positive or negative changes that took place but were not sufficient to result in a change in political rights or civil liberties ratings.

* indicates a country’s status as an electoral democracy.

RELATED TERRITORIES

DISPUTED TERRITORIES

Leaders who rely on “modern authoritarianism” have found subtle but effective techniques. Such leaders devote full-time attention to the challenge of crippling the opposition without annihilating it, and flouting the rule of law while maintaining a plausible veneer of order, legitimacy, and prosperity.

|

评分

-

1

查看全部评分

-

|