|

|

【中文标题】耐克与阿迪达斯的世界杯之战

【原文标题】World Cup Shootout: Can Nike Beat Adidas at Soccer?

【登载媒体】商业周刊

【原文作者】Brendan Greeley

【原文链接】http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-05-15/2014-world-cup-nike-adidas-gear-up-for-soccer-duels-next-round#r=hpt-tout

接到法比奥•科恩特朗的传球之后,卡里姆•本泽马轻轻一挡,球钻进了右边网窝。这是那天晚上的唯一进球,但相当精彩。凭借此球,皇家马德里在主场圣地亚哥伯纳乌体育场取得了胜利。

本泽马穿着阿迪达斯球鞋,科恩特朗也穿着阿迪达斯球鞋;皇家马德里穿着阿迪达斯球衣,对手拜仁慕尼黑也穿着阿迪达斯球衣。这两支俱乐部足球队同其它几支世界顶尖球队,正在进行冠军杯的半决赛。阿迪达斯赞助了这场赛事,它有权提供足球并在体育场上冠名。球队、球队、球场、足球、助攻、破门:阿迪达斯在伯纳乌度过了美好的一晚。

这是阿迪达斯66年来一贯的做法。这家公司首创这种营销方式,付钱给运动员请他们穿上自己的球鞋;付钱给球队请他们穿上自己的球衣;付钱给俱乐部请他们使用自己的足球。在70年代,这家公司的地位极为强大。俄勒冈一个销售日本运动鞋的人名叫菲尔•奈特,他把阿迪达斯当作自己的目标,当时看来是荒唐可笑的事情。

奈特现在是耐克公司董事会主席。伯纳乌球场的进球起始于克里斯蒂亚诺•罗纳尔多右脚上的耐克球鞋,他从中场给科恩特朗传出一记威胁球。我在现场观赛,因为耐克给我提供了球票。我之所以来到西班牙,是因为在多次要求采访耐克公司在俄勒冈的高管之后,他们坚持请我到马德里来。

耐克租下了具有380年历史的国王厅,这个稍显破败的宫殿建于菲利普四世。整整两年时间里,耐克在宫殿内外摆满了设备来安装布景。2013年,罗纳尔多赢得了“欧洲足球先生”——金球奖,这让他跻身于世界顶级球员。耐克邀请了全世界250名记者来到马德里,想让他们看到罗纳尔多的新球鞋。

耐克现在是世界上最大的运动穿戴品公司,年收入250亿美元,17%的市场占有率。第二位的公司是德国的阿迪达斯,年收入200亿美元,12%的市场占有率。在足球类穿戴品中,两家公司一共占据70%的市场份额。据国际足联提供的信息,全球有3亿人踢足球,10亿人观看足球比赛。这项运动在亚洲的普及率不断提升,美国也是一个处于增长期的市场。美国小型体育用品生产商,比如Under Armour和Warrior Sports也开始赞助英国巴克莱超级足球联赛(译者注:指英超)的球队,因为他们意识到球场上如果不出现他们的球鞋,就无法真正走向世界。

耐克说它2013年在足球产业中的收入为19亿美元,阿迪达斯拒绝透露这个信息,但根据莱茵一位市场咨询师彼得•霍尔曼提供的数字,去年公司的足球产业收入为24亿美元。这到底是否算是一场竞争,阿迪达斯也不大确定。知道1994年美国世界杯的时候,耐克还没有涉足足球产业。阿迪达斯在其它体育产业中失去了竞争优势之后,才转投足球。阿迪达斯公司的CEO赫尔伯特•海内喜欢说,这项运动是“我们的DNA”。阿迪达斯更加依赖欧洲市场,足球是那里唯一重要的运动项目。耐克希望涉足足球,而阿迪达斯需要足球。

阿迪达斯从1970年开始赞助国际足联,去年赞助合同被延期到2030年。据霍尔曼提供的信息,公司每四年的花费大约为7000万美元。公司还以稍低一些价格赞助欧洲足协。这项运动给阿迪达斯带来的收入比例高于耐克,阿迪达斯的产品销量在“赛事年”会显著增长,比如2010年南非世界杯期间。

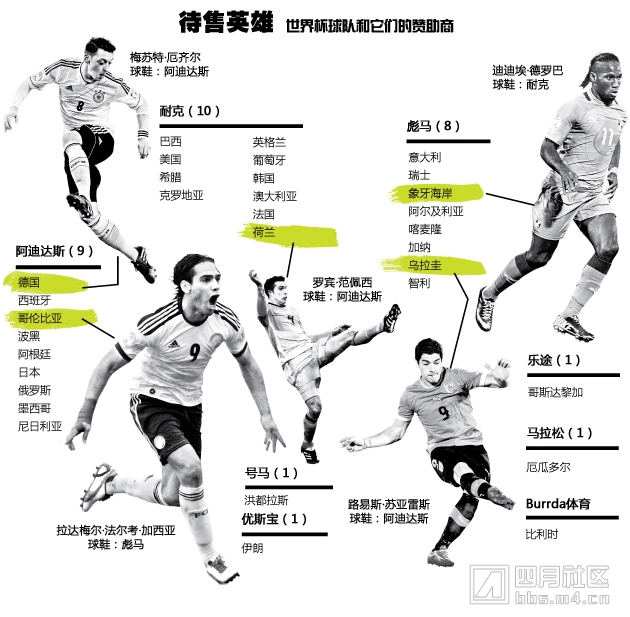

6月12日在圣保罗,巴西与克罗地亚的对阵是今年世界杯的揭幕战。霍尔曼说,公司单独为每家球队提供赞助,总金额达4亿美元。耐克赞助10只球队,高过以往赞助的球队数量,也比阿迪达斯赞助的球队多一个。耐克有巴西、葡萄牙和罗纳尔多;阿迪达斯有西班牙、德国和里奥内尔•梅西——获得4次足球先生称号的阿根廷球员。从1970年开始,每届世界杯的比赛用球都是阿迪达斯提供的。

对地球上大多数人来说,这项锦标赛是一件值得放弃工作的大事。阿迪达斯尤其盼望一个丰收的夏天。去年,公司的整体业绩令人失望,于是海内再次强调在2014年达成20亿欧元(27亿美元)足球产业销售额的目标。阿迪达斯在5月份公布,第一季度足球产业业绩增长27%,公司对于达成全年目标充满信心。但即使天遂人愿,还有另外一个问题——世界杯已经不是唯一的全球赛事了。

假如你生活在十年前的德国,你会观看德国足球甲级联赛和世界杯。如果你生活在英国,你会观看英超联赛和世界杯。所有世界顶尖球员每隔四年齐聚电视屏幕,付钱赞助国际赛事的确意义重大。一家全球体育营销集团的负责人安德鲁•沃尔什说,足球迷“非常珍视历史,阿迪达斯就是历史的一部分,这的确有极大的优势。”

但是国内联赛也已经变成了国际赛事。阿迪达斯注意到,在他的赞助下,德甲联赛在中国引起了越来越多的关注。在签下若干转播协议之后,英超联赛的全球收入仅在这个赛季就上升了25%。在星期六早晨,美国观众可以在NBC看到这个赛事,而且他们还看到比赛中使用的耐克足球。沃尔什说,像皇家马德里和拜仁慕尼黑这样的俱乐部球队变得越来越重要。过去,“阿迪达斯只冠名赞助世界杯,现在他们也参与了俱乐部赞助。”

即使在世界杯之年,耐克也很擅于做广告,暗示参与一个重大的世界足球赛事,而不提“世界杯”。它做广告的手法非常高明,似乎没有其它公司会这样做事。阿迪达斯依然在这个唯一的世界锦标赛中保持优势,而且在大把赚钱。但是耐克把它唯一的对手拉入一场昂贵的竞赛中:资助尽量多的优秀球员和球队。

特雷弗•爱德华兹是耐克品牌经理,他坐在国王厅三楼的会议室中说:“世界第一橄榄球靴,那就是我们,也包括德国。”他的话带有浓重的跨大西洋口音,因为这个英国人在俄勒冈居住了很长时间。他说“橄榄球靴”,意思是“足球鞋”。他说“德国”,意思是“阿迪达斯”。

位于德国南部城镇黑措根奥拉赫的一座阿迪达斯办公楼的地下室中,穿着球鞋的机械脚不停地踢球、踩踏。一个名叫“牛顿”的机器人在温控角落里枯燥地走来走去。阿迪达斯把他们赞助的9个国家队球衣穿在模特身上,排成一排向游客展示。足球事业部总监马提亚•麦肯和创意部安东尼奥•塞亚就是在这里开发出他们的新球鞋“silos”。

Silos并不是为某个运动员专门订制的球鞋,而是一种明星范,耐克和阿迪达斯都采取这样的策略。围绕特定运动员开发球鞋存在着风险。运动员的职业生涯有可能出人意料地终止,或者在一届世界杯比赛中表现极为糟糕,又或者仅仅是才华得不到展示。公司挑选一些球员,为他们开发一系列球鞋,让新运动员也使用同样系列的产品。梅西,被阿迪达斯称为最伟大的“财富”,有专为他配色的阿迪达斯球鞋,上面有定制的M标志。但是并没有梅西型号足球鞋,他穿的是F50系列,专为奔跑快速运动员设计的轻便球鞋。

赛亚在新泽西长大,他曾经在罗格斯大学踢足球。他拿起梅西的球鞋F50说:“这些穿F50球鞋的运动员,我们总会想到‘噢,这个人留这样的发型,他的车肯定有特殊的轮毂。’”赛亚和麦肯仔细研究比赛录像,分析运动员的动作,与专家讨论设计出silos。他们还会与孩子们交谈,了解他们希望如何踢足球。赛亚说:“小孩子总是想要成为下一个齐达内、下一个贝克汉姆、下一个梅西,你该怎么迎合他们呢?我想办法让自己认同他们踢球的方式。”

阿迪达斯期待梅西在今年夏天上演他特有风格的足球。公司把他抬升到其它球员完全无法匹敌的高度。(一位高管认为恐怕不能用“神”来形容他,但赞同“半神”这个词。)梅西是获得世界足球先生称号次数最多的球员,凭借5英尺7英寸的身高,他没有杂耍般炫目的技法,也没有高人一头的盘带技术,跳蚤——梅西的绰号——只是比所有人速度都快。他控球是无人可以追得上,之后就是轻松进球得分。在黑措根奥拉赫附近纽伦堡市的一家阿迪达斯商店里,你可以买到德国国家队队服和梅西的阿根廷球衣。在墙上有两句名言,一句来自梅西,一句来自阿迪•达斯勒(译者注:阿道夫•阿迪•达斯勒,阿迪达斯公司的创始人。)。

阿道夫•阿迪•达斯勒在二十世纪二十年代就是在黑措根奥拉赫开始制作运动鞋,阿迪达斯的总部目前依然在那里。员工们通常管这座城市叫“黑措”。阿迪达斯公司的生产理念完全围绕阿迪当初的设想:修鞋匠、与运动员交谈、制作足球鞋,就像赛亚和麦肯今天做的事情一样。

阿迪的儿子赫斯特才是在体育营销领域中享受到苹果掉落那一刻的人,他在1956年发现,如果他愿意免费提供产品,奥运会运动员就会穿上阿迪达斯的鞋。接下来的三十年,赫斯特跑遍整个世界,逐渐形成了运动行业现象的营销模式:竞价请运动员穿上他的衣服。赫斯特还首先了解到,不仅仅是运动员,连赛事也可以买到。他于是与国际足联建立了长久的合作关系,后来像可口可乐这样的跨国公司也采取了同样的做法。

当你今年夏天在巴西看到球场上阿迪达斯的三条横杠时,那是赫斯特的功劳。比赛用球,这次的名字叫做“brazuca”——葡萄牙语的“巴西人”——也是赫斯特的功劳。阿迪达斯总部矗立着两个直径10英尺的brazuca。赫斯特于1987年去世,但是他并没有一个像父亲一样的雕像。

马科斯•包曼坐在阿迪达斯勒体育场的露天看台上,说:“足球根植在这家公司里。”包曼小的时候,他心目中的英雄是塞普•马耶尔——拜仁慕尼黑队守门员,曾经在1974年与德国国家队一起获得世界杯冠军。在20多岁时,包曼在德国一家半职业球队任守门员。他曾经有马耶尔的球衣和手套,都是阿迪达斯的产品。包曼说:“当时,几乎所有赛事的赞助商都是阿迪达斯。”今年48岁的包曼身体条件很好,依然可以做守门员打比赛。他是公司足球事业部的负责人。他交易球星。

什么才能算作是阿迪达斯在2014年的成功?他说:“德国队赢得世界杯。”这既是情感上,也是专业上的回答。自从德国队穿着阿迪达斯球鞋在1954年瑞士世界杯上夺冠之后——他们说这是“伯尔尼奇迹”,公司就一直赞助德国国家队。每次世界杯开赛前一年,阿迪达斯和耐克都要进行一次例行的比拼——宣布谁的胸前会出现他们的标志。这不仅仅是数量的比拼,两家公司都想赞助一个冠军——包曼说:“三条杠举起奖杯。”——而且想赞助一个公民有体面收入的国家。

德国,7次打入世界杯决赛,3次捧杯,是当之无愧的选择,即使没有阿迪在伯尔尼奇迹中的功劳。同样还有西班牙,那里的市场不大,但红色风暴在2010年席卷全球。2011年,阿迪达斯签下哥伦比亚,去年他们把合同延长到2022年。哥伦比亚目前在国际足联中排名世界第五,同样重要的是那里有一个不断壮大的中产阶级。耐克和阿迪达斯在去年11月份,赶在圣诞节之前开始出售国家队服装。包曼说从那时开始,哥伦比亚队服在拉丁美洲销量是阿迪达斯的销量之最。

然而,买下一支国家队的冠名权并不等于买通了整个国家。据莱普卡姆提供的数据,阿迪达斯的Facebook足球主页在哥伦比亚有40万粉丝,而耐克有100万。阿迪达斯赞助墨西哥队,在那里有90万粉丝,耐克有390万。其它国家情况大致如此。但目前尚不明了的是,在足球领域中社交媒体会对销量产生多大的影响。服装销售就像政治活动,互联网上发生的事情无关痛痒,除非影响到销量。

一年半之前,阿迪达斯开始与哥伦比亚的零售商沟通,根据以往国家队队服的销售情况逐个城市确定需求量。阿迪达斯还有自己的策略,它根据哥伦比亚国家队在巴西世界杯上可能的表现预测球衣的销售前景。阿迪达斯在哥伦比亚储存了一些空白的球衣,如果某个球员在今年夏天表现突出,它可以临时在球衣上印上名字。根据欧洲联赛中国际球员的表现,哥伦比亚前锋亚得里安•拉莫斯的球衣或许会在柏林出售,他今年在那里踢球,甚至还会在他秋季即将效力的多特蒙德出售。

哥伦比亚人也在美国居住,阿迪达斯对此了如指掌,他们准备好在那里做销售。阿迪达斯北美足球事业部总监埃内斯托•布鲁斯说,公司赞助墨西哥球衣是为了迎合美国的球迷。他说:“墨西哥国家队在美国极受欢迎,他们的比赛体育场座无虚席,球迷众多。”墨西哥球衣是阿迪达斯在美国的销量冠军,足球产品销量最好的地方是加利福尼亚、德克萨斯和亚利桑那。

美国消费者的雄厚实力让这个国家成为阿迪达斯最大的单一足球市场,占全球足球产品销量的15%。5月份,阿迪达斯的海内上报美国的足球产品销售额出现“两位数”增长,而耐克的销量增长更高,那是因为美国国家队的队服上印着一个大对勾。但是阿迪达斯是美国足球大联盟服装的独家赞助商,2005年,它接手耐克的青年训练营,改名为“阿迪达斯一代”。然而,美国人唯一认为重要的名字是一个外国人——里奥内尔•梅西。

布鲁斯说这个阿根廷人是美国排名第七位的运动员,也是唯一跻身前十位的足球运动员。他知道美国年轻人在寻找偶像,“我们有世界上最伟大的体育明星”。布鲁斯对跳蚤赞不绝口。在阿迪达斯看来,梅西就是一个超级明星黏合剂,他团结了全世界的拥护者。

在与包曼参观阿迪达斯的园区时,我提到了他自己的一段经历。2000年之后的两年中,包曼在耐克工作,向德国人销售耐克球鞋。他试图用一种相对有策略的方式来比较两个公司,他说耐克“更有美国味”。我问他这是什么意思,他说:“嗯,或许是更……”他想了一下,继续说,“我认为是更加以市场为导向。”这让我想到阿迪•达斯勒是一个修鞋匠。

国王厅三楼的天花板上,绘制着曾经的帝国边陲景色的壁画——纳瓦拉、加利西亚、佛兰德斯、墨西哥。耐克在下面竖起穿着世界杯比赛服的21个人体模特,10支球队,分别穿主客场服装,巴西额外多一个。他们按球队的重量级排列,巴西在最前面,马马虎虎的澳大利亚在最后面。每个模特身高大约7英尺,由脚下的光源照亮。

在另一些房间里,耐克安装了几个国家的木制的框架,看起就像球员的更衣室,里面还挂着比赛服、护腿、内衬裤和妥协。真人大小的运动员模特站在锁柜前回答问题——葡萄牙的佩佩、巴西的路易斯•古斯塔沃。克罗地亚没有锁柜,皇家马德里中场球员卢卡•莫德里奇就穿着客场球衣站在那里。

他小时候最喜欢的球员是克罗地亚的11号队长兹沃尼米尔•博班,这支球队在1998年爆冷获得世界杯第三名。他的第一双足球鞋是耐克。“长大之后我的需求变得更加复杂,不像小的时候,你只关心鲜艳的颜色。”耐克的市场占有率从2000年开始提升,部分原因在于新退出了一系列色彩鲜明的球鞋。莫德里奇在今年夏天将穿上耐克Mercurials。他身后是157只橙色的球鞋从天花板上垂下来,就像水晶吊顶上的装饰。

菲尔•麦卡特尼站在荷兰国家队的锁柜前,他负责管理耐克所有的鞋类产品。他在纽卡斯特尔长大,曾经接受过短跑训练。当我提到英格兰国家队在世界杯历史上平平的表现时,他的反应很得体。麦卡特尼描述鞋类产品开发的过程与麦肯和赛亚的描述基本一致:观察明星、观看大量的比赛、与专业人士交谈、与孩子交谈。

他身后摆着一双Air Jordan,荷兰橙的配色。我问他足球界是否会出现迈克尔•乔丹式的人物——不仅仅是天赋异禀的天才,而且可以在退役之后形成一个品牌。他说:“比赛是由关键时刻决定的。我认为如果我们能把产品的创新与运动员和关键时刻形成连接,才算是成功的策略。”换句话说,不。

马德里:耐克品牌总监爱德华。

爱德华负责运作公司的所有品牌,我在橙色的Air Jordan展台前见到了他。他今年50岁,是崇拜贝利的那一代人。爱德华讲了很多的“故事”和“与消费者的联系”,我起初觉得他在回避我的话题,但后来发现他很直率。

阿迪达斯赞助运动员和球队,为他们提供新研发的球鞋,希望他们取胜。耐克也在做同样的事情,但对现实的依赖不那么强烈。2008年,英国导演盖伊•里奇以一名年轻球员的视角拍摄了一部耐克广告,他从一家荷兰地方俱乐部进入阿森纳队踢球。影片中你看不到球员本人,只有克里斯蒂亚诺•罗纳尔多和曼联队的韦恩•鲁尼等人冲来撞去、骂脏话。这位球员刻苦训练到呕吐、球技越来越高、把妹、再把妹、得到队友的认可,最终代表荷兰国家队走上世界最大的舞台。

耐克了解球场上真实发生的事情,还会用它的球员来讲述一个美丽的故事。你作为一个消费者对这个广告的记忆对耐克无比重要。

第二天,一对记者来到国王厅二层,他们穿过一条走廊,两边展柜中摆放的是老款耐克球鞋和一些球迷的黑白照片。耐克把大厅布置得像一个小型体育馆,类似于那种没有座位的台阶式看。这种建筑风格在1989年西尔斯堡灾难之后就没有被作为甲级联赛的比赛场地,当时有96名球迷在英格兰一所体育馆的垮塌事故中丧生。

耐克新球鞋的首次发布。

耳机已经准备好,有英语、西班牙语、葡萄牙语、汉语、日语和韩语的同声传译。一块屏幕正在播放这家公司在为今年夏天准备的广告:孩子们在踢足球,他们一个一个地变成了职业选手——罗纳尔多、鲁尼——在某个全球足球锦标赛中代表自己的国家出战,或许是世界杯,但广告中没有明确提及。这种拍摄模式与阿迪达斯在2006年的成功广告息息相关,两个孩子在土场地上挑选队员,随着一个个名字被叫到,巨星们纷纷登场——贝克汉姆、齐达内(译者注:甚至还有贝肯鲍尔和普拉蒂尼)。

但是耐克的广告让人感觉不同凡响,它暗示了一个体育盛会,甚至拥有它而无需支付费用。它在2012年夏天用“Find Your Greatness”实施了这个策略,阿迪达斯在当时支付了2亿美元赞助伦敦奥运会。同样在1984年,匡威赞助洛杉矶奥运会时,耐克在电视上推出它自己的运动员,并且请兰迪•纽曼演唱歌曲《我爱你洛杉矶》。现在匡威是耐克的下属品牌。

在马德里的一个体育场内,大屏幕在放映罗纳尔多在宫殿中奔跑。然后白光闪过,银幕升起,真正的克里斯蒂亚诺•罗纳尔多出现了。他穿着葡萄牙国家队的球衣和刺客球鞋,还有红色的球袜和护踝。他走下球场,摆弄着一只足球,然后回到看台上接受采访。他的头发打理得很好看。市场咨询师霍尔曼说:“耐克的球员都有娱乐天赋,克里斯蒂亚诺•罗纳尔与其说是一个球员,更像是一个明星……阿迪达斯的莱昂内尔•梅西只是一个球员。阿迪达斯支持运动员,耐克支持体育明星。”

在看台上面的一层,耐克在一个小房间里安装了一个破旧的木制更衣室。里面有两把皮椅子和一个箱子,这里面的所有用品都来自一个虚拟的球队“耐克FC”,也就是耐克足球俱乐部。这是耐克为场外生活设计的服饰品牌,耐克FC的球员都是黑白照片。这家公司进入足球产业已经20年,但是就像阶梯式看台一样,这个房间是为了唤醒人们在耐克进入市场之前的怀旧情绪。

一个锁柜中挂着一张照片,下面的名字是巴西人罗纳尔多,他在2002年世界杯决赛与德国队的比赛中进了两个球。照片下面是比赛中使用的耐克毒蜂球鞋,和一个有签名的老式耐克足球,好像这就是当时的比赛用球。但是2002年世界杯实际使用的足球是阿迪达斯的“飞火流星”。十几年之后你完全可以假装赞助了世界杯,所以或许没有理由真的这么做。

原文:

On a cross from Fabió Coentrão, Karim Benzema, with a single touch, puts the ball in the right place. It’s the only goal of the night, but it’s beautiful, and with it Real Madrid wins at its home stadium, the Santiago Bernabéu.

Benzema wears Adidas (ADS:GR) cleats. So does Coentrão. Real Madrid wears Adidas jerseys. So does Bayern Munich, the other team. The two clubs, among the best in the world, are playing in a semifinal match for the Champions League. Adidas sponsors the league, which gives it the right to supply the ball and put its name on the field. Team, team, field, ball, assist, goal: a good night for Adidas at the Bernabéu.

This is what Adidas has been doing for 66 years. The company helped invent the practice of paying athletes to wear its shoes, paying teams to wear its jerseys, and paying a league to use its ball. In the 1970s the company was so dominant that a man named Phil Knight, selling Japanese track shoes in Oregon, set Adidas as his target. It seemed absurd at the time.

Knight is now the chairman of the board at Nike (NKE). That one goal at the Bernabéu started with a Nike cleat on the right foot of Cristiano Ronaldo, who fed Coentrão with a threaded pass from midfield. I’m at the stadium because Nike offered me tickets. And I’m in Spain because after several requests to speak to executives in Oregon, Nike insisted I meet them here in Madrid.

Nike has rented out the 380-year-old Salón de Reinos, the slightly shabby remains of a palace built by Philip IV. For two days, Nike has parked generators outside and installed stage sets inside. In 2013, Ronaldo won the Ballon d’Or, the golden ball. This makes him the best player in the world. Nike invited 250 journalists from around the globe to Madrid because it wants us to see Ronaldo’s new shoes.

Nike is now the largest sportswear company in the world, with $25 billion in revenue and a 17 percent market share. The second-largest, Germany-based Adidas, has $20 billion in revenue and 12 percent of the market. These share numbers soar for soccer gear, where together the two comprise 70 percent of the market. According to FIFA, the organization that governs international soccer, 300 million people play the game and a billion watch it. The sport is expanding in Asia and is the rare product for which the U.S. is still a growing market. Smaller American sportswear providers such as Under Armour (UA) and Warrior Sports have begun sponsoring teams in the U.K.’s Barclays Premier League, recognizing that a company without a cleat on this turf cannot aspire to be global.

Nike says it brought in $1.9 billion in soccer revenue in 2013. Adidas declined to share its number, but according to Peter Rohlmann, a sports marketing consultant based in Rheine, last year the company had $2.4 billion in soccer revenue. That this is even a contest is a problem for Adidas. Nike didn’t do soccer until 1994, when the World Cup came to the U.S. And even when Adidas lost its advantage in other sports, it held on to it in soccer. Herbert Hainer, the company’s CEO, likes to say that the game is “part of our DNA.” Adidas relies more on the European market, where soccer is the only sport that matters. Nike wants soccer. Adidas needs it.

Since 1970, Adidas has sponsored FIFA. Last year it extended that agreement to 2030; according to Rohlmann, this costs the company almost $70 million for every four-year cycle. For slightly less than that, Adidas also sponsors UEFA, which runs international soccer in Europe. The sport makes up a larger part of overall revenue for Adidas than it does for Nike, and Adidas’s sales jump in “event years,” as in 2010, when the last FIFA World Cup was played in South Africa.

On June 12 in São Paulo, Brazil will play Croatia in the first game of this year’s World Cup. The corporate spend on team sponsorships alone, according to Ohlmann, will total almost $400 million. Nike will sponsor 10 national teams, more than it ever has before—and one more than Adidas. Nike has Brazil, Portugal, and Ronaldo. Adidas has Spain, Germany, and Lionel Messi, the Argentine who has won the Ballon d’Or four times. As in every World Cup since 1970, the ball on the field will be Adidas’s.

For most of the planet, the tournament will be a work-stopping big deal. Adidas, in particular, is counting on a huge summer. Last year was a disappointing year overall for the company, so Hainer has been emphasizing an old promise to produce €2 billion ($2.7 billion) in soccer revenue in 2014. In May, Adidas reported first-quarter soccer growth of 27 percent, and the company projects confidence that it will meet its target. But even if it does, it has another problem. The World Cup is no longer the only global tournament.

As recently as a decade ago, if you lived in Germany, you watched the Bundesliga and the World Cup. If you lived in the U.K., you watched the Premier League and the World Cup. All the world’s best players used to appear on the world’s TV screens only once every four years; paying to own international contests made sense. Soccer fans are “very precious about history,” says Andrew Walsh, a director at Repucom, a global sports marketing group. “Adidas has been a part of that, and that carries some weight.”

But the national leagues themselves have become international contests, too. Adidas has noticed increased interest in the Bundesliga, which it sponsors, in China. With several new broadcasting deals, global revenue for the Barclays Premier League rose 25 percent this season alone. On Saturday mornings, Americans can watch the league on NBC. And when they do, they see Nike’s ball on the field. Club teams like Real Madrid and Bayern Munich are more important now, says Walsh. In the past, “[Adidas] could just stick their name on the World Cup and that did it,” he says.

Even during cup years, Nike has become adept at running ads that imply a major global soccer event without uttering “FIFA World Cup.” Nike is so good at advertising and event promotion that it sometimes seems as if no other company is even playing the same game. Adidas maintains an overwhelming advantage at the only global tournament, and it still makes more money in the sport. But Nike is drawing its only real rival into an old and expensive game: Sponsor as many of the best teams and players as possible.

“The No. 1 football boot brand in the world, that’s what we are today,” says Trevor Edwards, sitting on the third floor of the Salón de Reinos, “including Germany.” Edwards, head of brand management for Nike, speaks with the vaguely trans-Atlantic accent of an Englishman who’s lived in Oregon for a long time. When he says “football boot,” he means soccer cleat. Nike does, in fact, sell more of those. And when Edwards says “Germany,” he means Adidas.

In a basement at an Adidas building in the southern German town of Herzogenaurach, mechanical feet never tire of kicking goals and stomping cleats. A sad robot named Newton walks and sweats in a climate-controlled enclosure in the corner. For visitors, Adidas has lined up its nine national team jerseys on mannequins. Newton roots for Germany. This is where Matthias Mecking and Antonio Zea, heads of soccer marketing and soccer innovation, respectively, come up with their cleat “silos.”

Silos are shoes dedicated not to players but to player styles. It’s how both Nike and Adidas approach soccer cleats. It’s risky to make shoes that are branded around a single player. Athletes can fade unexpectedly, have a catastrophic World Cup summer, or simply fail to live up to their talent. The companies pick their players, move them into a line of cleats, then move new players up the same line as they arrive. Messi, the greatest of what Adidas calls its “assets,” has his own color scheme at Adidas, his own stylized M logo. But there is no Messi cleat. He wears a version of the F50, a light shoe designed for fast players.

Zea grew up in New Jersey and played soccer for Rutgers University. He picks up the F50, Messi’s choice. “This F50 player,” he says, “we always thought, ‘Oh, the guy with the hair, and he’s got the car with rims on it.’ ” Zea and Mecking watch game tape, analyze movements, and talk to pros to identify silos. But they also talk to kids about the way they play and how they’d like to play. “As a little kid, you want to be the next [Zinedine] Zidane, the next Beckham, the next Messi,” says Zea. “How do you do that? Well, I align myself with their styles of play.”

Adidas is counting on Messi’s style of play this summer. The company has elevated him to something above all the rest of its players. (One executive resisted the word “god” but consented to “demigod.”) Messi has won the Ballon d’Or more than any other player. At 5-foot-7, he doesn’t do acrobatics, and he hasn’t patented any dribbling tricks. La Pulga—the flea—is just faster than everyone else. He puts the ball where they aren’t, and then he puts it in the goal. In the Adidas store at Nuremberg, near Herzogenaurach, you can buy German national team jerseys and Messi’s Argentina jersey. On the wall, there are two quotes: one from Messi and one from Adi Dassler.

Herzogenaurach is where Adolf “Adi” Dassler—adi das—started making sports shoes in the 1920s. Adidas is still based there. Employees often call the town “Herzo” to save time. Adidas’s company mythology is built around Adi: the cobbler, talking to athletes and making cleats, just like Zea and Mecking do today.

It was Adi’s son Horst, though, who had the falling-apple moment in sports marketing when he realized in 1956 that he could get Olympians to wear Adidas shoes if he just gave them away. For the next three decades, Horst ran around the world, refining what is now an accepted part of sports: bidding to pay athletes to wear his clothing. Horst also was the first to understand that not just the athletes but the event itself could be for sale. He created Adidas’s enduring relationship with FIFA and ensured that other multinationals like Coca-Cola (KO) could do the same.

When you see the three stripes of Adidas on the boards around the soccer fields in Brazil this summer, that’s Horst, not Adi. The ball, this time called the “brazuca,” after a Portuguese slang term for Brazilians—Horst. There are two 10-foot-diameter brazucas displayed like sculptures at Adidas. Horst died in 1987. But there’s no statue like the one of his dad.

“Soccer is rooted within the company,” says Markus Baumann, sitting on the wooden bleachers of Adi-Dassler Stadium. When Baumann was a kid, his hero was Sepp Maier, the goalkeeper for Bayern Munich who won a World Cup with the German national team in 1974. In his twenties, Baumann was a goalie at the semi-pro level in Germany. He used to have Maier’s jersey and Maier’s gloves, all made by Adidas. “At that time,” Baumann says, “almost everything was sponsored by Adidas.” Baumann, now 48 and still trim enough to play keeper, is the company’s head of soccer. He sells heroes.

What does success look like for Adidas in 2014? “Germany winning the World Cup,” he says. This is both an emotional and professional answer. The company has sponsored the German national team since it won in Adidas cleats at the 1954 Switzerland World Cup, an event Germans refer to as the “Miracle of Bern.” The year before every World Cup, Adidas and Nike hold a ritual weigh-in, announcing whose chests will be wearing their logos. This is not a simple competition for the highest number of teams. A company wants to back a winner—“three stripes lifting the trophy,” Baumann says—and wants a winner whose citizens have disposable income.

Germany, with three World Cup wins in seven finals appearances, would be an obvious choice even without Adi’s role in the Swiss miracle. Spain as well; it’s a smaller market, but La Roja won it all in 2010. In 2011, Adidas signed Colombia and last year extended the country’s contract until 2022. FIFA now ranks Colombia’s team fifth in the world. Just as important, it has a growing middle class. Both Nike and Adidas started selling their national team gear in November of last year, in time for Christmas. Baumann says that ever since, Colombia has been Adidas’s best-selling jersey in Latin America.

Buying the rights to a country’s jersey, however, doesn’t buy the entire country. According to Repucom, Adidas’s soccer page has 400,000 Facebook likes in Colombia. Nike’s has a million. Adidas sponsors Mexico and has 900,000 likes in the country. Nike has 3.9 million. It’s a consistent pattern, worldwide. But it’s not yet clear in soccer what impact social media has on revenue. Apparel sales are like politics. What happens online doesn’t matter unless it drives transactions.

A year and a half ago, Adidas started talking to retailers in Colombia, gauging demand city by city based on past sales of national team gear. Adidas also has its own multiplier, weighting demand for these jerseys based on bookies’ odds of the Colombian team’s chances in Brazil this summer. Adidas has generic jerseys stashed in Colombia, and if a particular player is having a good summer, it can add his name at the last minute. And the presence of international players in the European leagues means that the jersey of Adrián Ramos, a Colombian forward, will sell in Berlin, where he played this year, and possibly even in Dortmund, where he will play in the fall.

Colombians live in the U.S., too. Adidas knows where, and is prepared to sell to them. Ernesto Bruce, head of soccer for Adidas in the U.S., says the company sponsors Mexico’s jersey to get to the team’s American fans. “The Mexican national team in the U.S. is tremendous,” he says. “They sell out stadiums. They have a rabid fan base.” Mexico’s jersey is Adidas’s top seller in the U.S., and all of the company’s soccer products sell best in California, Texas, and Arizona.

The sheer strength of the American consumer makes the country, surprisingly, Adidas’s largest single market for soccer, 15 percent of global soccer revenue. In May, Adidas’s Hainer reported “double-digit” soccer growth in the U.S., conceding that Nike’s growth was even higher. There’s a Nike swoosh on the U.S. national team jersey. But Adidas is the sole sponsor for the uniforms of Major League Soccer and in 2005 took over Nike’s youth development camp in the U.S., retitling it “Generation Adidas.” The only individual name that matters in the U.S., however, is a foreigner: Lionel Messi.

Bruce points out that the Argentine is the seventh-most-followed athlete in the U.S., the first soccer player to crack the top 10. He sees kids in America looking for icons. “We have the world’s biggest sports icon,” he says. Bruce talks quite a bit about La Pulga. For Adidas, Messi is a kind of superstar mortar, filling in the cracks between the world’s allegiances and holding them all together.

Walking through the Adidas campus with Baumann, I bring up a specific part of his own history. For two years in the early 2000s, Baumann worked for Nike, selling its cleats to Germans. He struggles to find a diplomatic way to compare the two companies and says that Nike is “more American.” When asked what he means, he says, “Yeah, probably more …” then thinks for a second. “More marketing-driven, I would say.” He reminds me that Adi Dassler was a cobbler.

Frescoes on the ceiling of the third floor of the Salón de Reinos list outposts of an empire that has disappeared: Navarra, Galicia, Sicilia, Flanders, Mexico. Below them, Nike has clad 21 mannequin torsos in its World Cup team uniforms—10 teams, each with a home and away kit, and one extra for Brazil. They’re arranged in order of relative importance, Brazil at the front, Australia’s poor Socceroos at the end. Each torso is lit from below and raised to suggest a 7-foot-tall player.

In other rooms, Nike has installed frames that look like locker rooms for several countries and hung them with matching jerseys, leggings, swim trunks, flip-flops. Real live national team players stand in front of their lockers and answer questions—Pepe for Portugal, Luiz Gustavo for Brazil. There is no locker for Croatia, and so Luka Modrić, a precise passer in the midfield for Real Madrid and Croatia’s national team, stands under a 7-foot-tall torso wearing Croatia’s away jersey.

His favorite player when he was a kid was Zvonimir Boban, captain of the Croatian 11 that had a sweetheart run to a bronze in the 1998 World Cup. His first cleat as a child was a Nike. “Today I am more demanding, not when I was a kid,” he says. “At that time you are not caring, you just want to have some nice colorful boots.” Nike increased market share in the early 2000s in part with a line of bright cleats. Modrić will wear Nike’s Mercurials this summer. Behind him, 157 cleats in lime and orange hang from the ceiling like crystals in a chandelier.

Phil McCartney is in front of the locker room for the Netherlands. McCartney manages all of sports footwear for Nike. A runner by training, he grew up in Newcastle and is tactful when I poke at England’s regular disappointment at the World Cup. McCartney describes the exact same process of silo-creation as Mecking and Zea at Adidas: Look at stats, watch an ungodly amount of soccer, talk to pros, talk to kids.

Behind him is a pair of Air Jordans with a Dutch orange swoosh. I ask whether there will ever be a Michael Jordan of soccer—not just a transcendent talent but one who creates a brand that remains when the player has left the field. “The game is defined by key moments,” he says, “and I think when we can link product innovation to key athletes, to key moments, that’s when the magic happens.” In other words, no.

In Madrid: Nike branding chief Edwards

Edwards, the guy who runs all of branding for the company, also meets me in front of the Dutch Air Jordans. He is 50, just old enough to have been a Pelé guy when he was a kid. Edwards talks a lot about “stories” and “connecting with the consumer.” I think he is being evasive, and then I realize he’s completely straightforward.

Adidas sponsors athletes and teams, supplies them with innovative shoes, and hopes they win. Nike does all that, too, but relies less on reality. In 2008, Guy Ritchie, the English auteur, directed a Nike commercial from the point of view of a young player, called up from a Dutch regional league to play for Arsenal. You never see the player, just Cristiano Ronaldo and Manchester United’s Wayne Rooney as they rush by and trash talk. The player trains until he vomits, gets better, gets the girl, gets another girl, earns the approval of his teammates, and in the end the player walks on the field for the Dutch national team on the world’s biggest stage.

Nike has realized that while what actually happens on the pitch matters, it can also use its players to tell elegant fiction. What you, the consumer, remember matters just as much as what actually happened.

The next day, the horde of journalists walks up to the second floor of the palace and through an alley lined with old Nike cleats in glass cases and black-and-white footage of soccer fans. Past the alley, Nike has built seating that looks like a small stadium. It has been painted to resemble seatless concrete terraces, a construction style that’s gone out of fashion at most first-league soccer stadiums since the Hillsborough disaster of 1989, when 96 fans were crushed in a panic at a stadium in England.

The debut of Nike’s new cleat

Headphones are laid out for simultaneous translation into English, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. A video shows the company’s ad campaign for this summer: Kids play soccer, and one by one they become pros—Ronaldo, Rooney—playing international soccer in some kind of tournament of global significance, perhaps the FIFA World Cup, which is never mentioned. The ad owes something to a successful Adidas campaign from 2006, when two kids on a dirt field began to pick teams and pros trotted out as their names were called—Beckham, Zidane.

But Nike’s new ad also shows what the company has always done best. It hints at an event, owning it without ever having to pay for it. It did this with a campaign in the summer of 2012, “Find your greatness,” coincidentally a summer in which Adidas paid $200 million to sponsor the London Olympics. And it did this in 1984. When Converse sponsored the Los Angeles Olympics, Nike featured its own athletes in a TV ad as Randy Newman in a convertible sang I Love L.A. Now Nike owns Converse.

In the faux stadium in Madrid, a video shows Ronaldo hustling through the palace. There is a flash of white light, the screen lifts, and there is the actual Cristiano Ronaldo. He’s wearing his Portugal uniform and his new superlight cleats, essentially a pair of red socks with a heel cup and studs. He walks down a turf catwalk, briefly juggles a ball, and then returns to the stage for an interview. He has excellent hair. “The players from Nike have a lot of entertainment character,” says Rohlmann, the marketing consultant. “Cristiano Ronaldo, he’s much more a star in a broader sense than a football kicker. … Lionel Messi, sponsored by Adidas, he’s more a football kicker.” Adidas backs athletes. Nike backs athletic celebrities.

On the floor above the stage set, Nike has installed distressed wooden cabinets in a small room. There are two leather chairs and a chest, and the cabinets hold gear from a fictional entity called “Nike FC.” This is the Nike Football Club. It’s a brand of lifestyle gear to be worn off the field. The players of Nike FC are shot in black and white. Nike’s made soccer gear for 20 years now, but like the painted concrete terrace on the floor above it, the room is designed to evoke nostalgia for a time before it got in the game.

One cabinet features photos of another Ronaldo, the single-named Brazilian. He scored twice in a 2002 World Cup finals win over Germany. Below the photos rest his Nike Mercurial cleats from the game, and a signed, aged Nike soccer ball. It’s as if he won with that ball, too, but in 2002 the actual ball on the field was the “fevernova,” made by Adidas. No reason to pay for the World Cup when in a dozen years you can simply pretend you did.

|

评分

-

1

查看全部评分

-

|