|

|

【中文标题】一百张最有影响力的照片 之七

【原文标题】Most Influential Photos

【登载媒体】时代周刊

【原文作者】Ben Goldberger

【原文链接】http://100photos.time.com/photos/harold-edgerton-milk-drop

地出

威廉姆•安得斯,美国宇航局

1968年

我们很难准确说出历史发生变化的精确时间。但是对于人类首次看到我们所生活的世界的美丽、脆弱和孤独,我们知道非常准确的时间。那是1968年12月24日,阿波罗8号宇宙飞船从卡纳维拉尔角升空,开始首次载人沿月球轨道飞行的75小时48分41秒。宇航员弗兰克•博尔曼、吉姆•洛维尔和比尔•安得斯在圣诞节前夜进入绕月轨道。那一年,美国经历了血腥、纷乱的一年。在总共10圈绕月轨道的第4圈,他们的飞船从月球远端绕行,舷窗中出现了一个蓝色的地球。“噢天啊!看那里!地球升起来了,哇,太美了!”安得斯喊道。他拍摄了一张照片,但使用了黑白胶卷。洛维尔匆忙去找彩色胶卷,安得斯说:“我们恐怕要错过这个景色了。”洛维尔看了看三号和四号舷窗,说:“嘿,在这里。”漂浮在无重力环境中的安得斯把哈苏相机镜头对准洛维尔的方向,拍摄了一张照片。洛维尔说:“拍到了吗?”安得斯说:“拍到了。”这张照片是第一次从地球以外拍摄的全彩色地球景象,它推动了环境保护运动的发展。同样重要的是,人们通过照片了解到,在寒冷、严酷的宇宙中,我们呈现出一种独特的美丽。

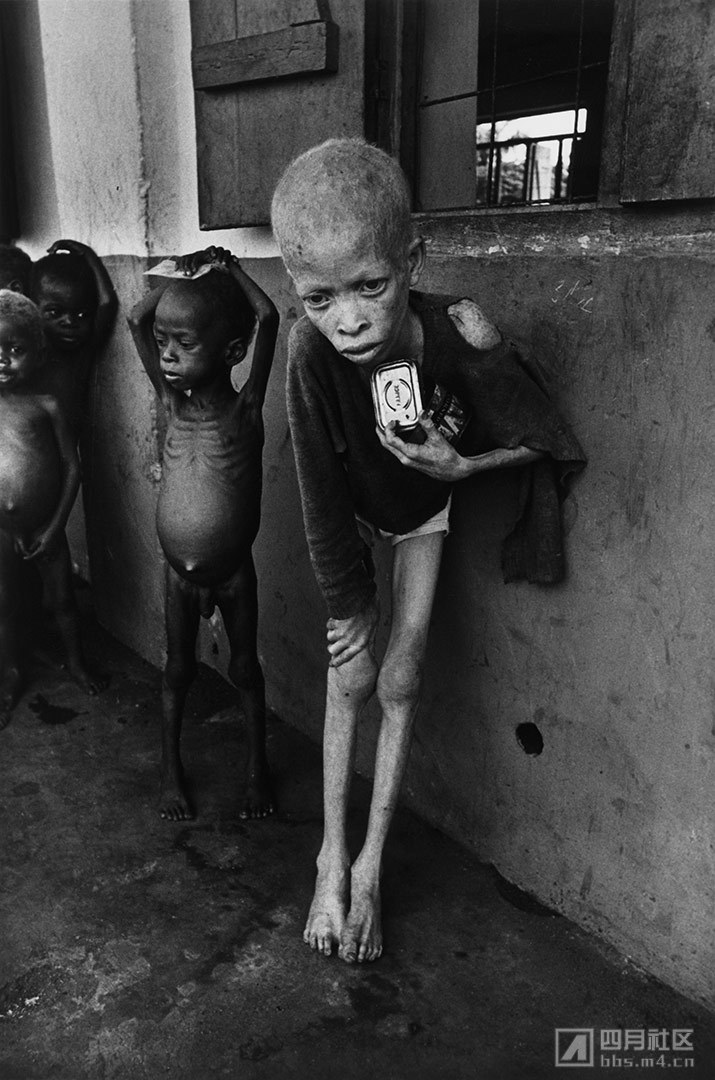

白化病男孩,比夫拉

唐•麦库宁

1969年

基本上没有人会记得比夫拉,这个西非小国在1967年从尼日利亚南部独立,三年后又被并回尼日利亚。大部分人对这个痛苦时期的了解,都来自于一些展示大范围的饥饿和夺取了数百万人生命的疾病的照片。其中最震撼的是英国战争摄影师唐•麦库宁拍摄的一个9岁白化病儿童的照片。麦库宁写道:“一个饥饿的比夫拉孤儿是最可怜的人,而一个饥饿的比夫拉白化病孤儿的境遇难以言表。他在饥饿中奄奄一息,但就算是这样,在其它孩子中他还会受到奚落、侮辱和排挤。”这张照片对公众的态度产生了深远的影响,迫使各国政府采取行动,大规模空投食品、药品和武器。麦库宁希望这些触目惊心的照片可以“直抵衣食无忧的人们的内心和灵魂”。公众的注意力被其吸引,麦库宁的作品也留下了具有深远影响力的遗产——他和其他见证战乱的人促成了“医生无国界组织”。这个组织为遭受战争、疾病和灾难蹂躏的人提供紧急医疗救助服务。

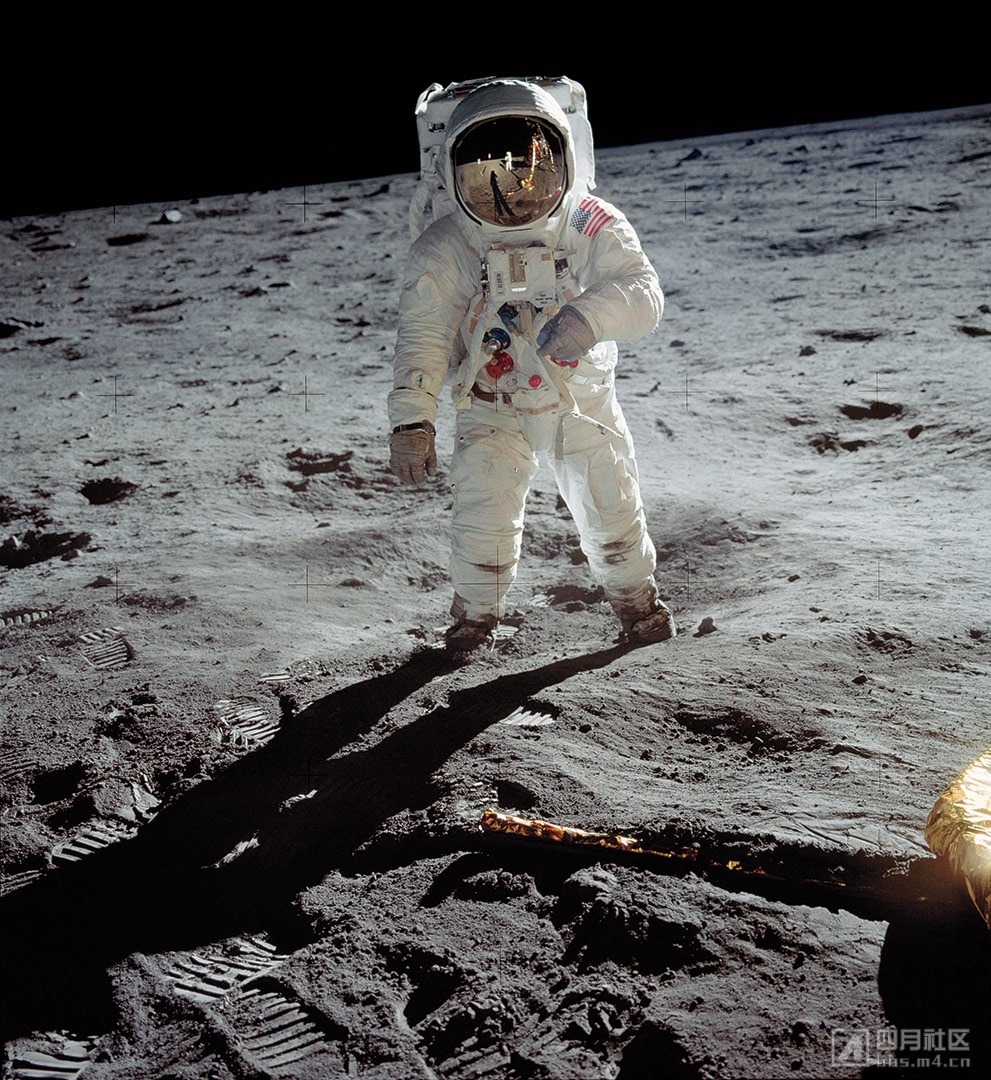

登月者

尼尔•阿姆斯特朗,美国宇航局

1969年

月球宁静海的某处,1969年7月20日晚上,巴兹•奥尔德林脚下的那个小小的凹陷,现在依然存在,那是点缀在月球古老地表上数十亿个陨石坑之一。但这算不上是宇航员所留下的最永恒的印记。

奥尔德林并不在乎第二个登上月球——在经过漫长的任务准备之后错过了具有划时代意义的机会,尼尔•阿姆斯特朗提前了几英寸、几分钟。但是奥尔德林争取到了另一个不朽的机会。阿姆斯特朗携带了一部70毫米哈苏相机,因此他负责拍摄照片,也就是说,地球人看到的一个登陆月球的照片,必然是第二个踏上月球表面的人。但是这张照片之所以永久流传,其实并没有足够的理由。这不是奥尔德林爬下登月舱舷梯的镜头,也不是他向美国国旗敬礼所彰显的爱国主义情绪。他只是站在那里,遥远世界里一个弱小的人——这个世界会毫不犹豫地夺走他的性命,只要他擅自移动精密太空服上的一个小零件。他的手臂笨拙地弯曲着,或许是在检查手腕上的任务清单。他的面罩上反射出更加渺小、如幽灵一般的阿姆斯特朗。如果说这张照片的目的是彰显人类的英雄形象,那么它完全没有达到这个目的。但实际上,它的确达到了。

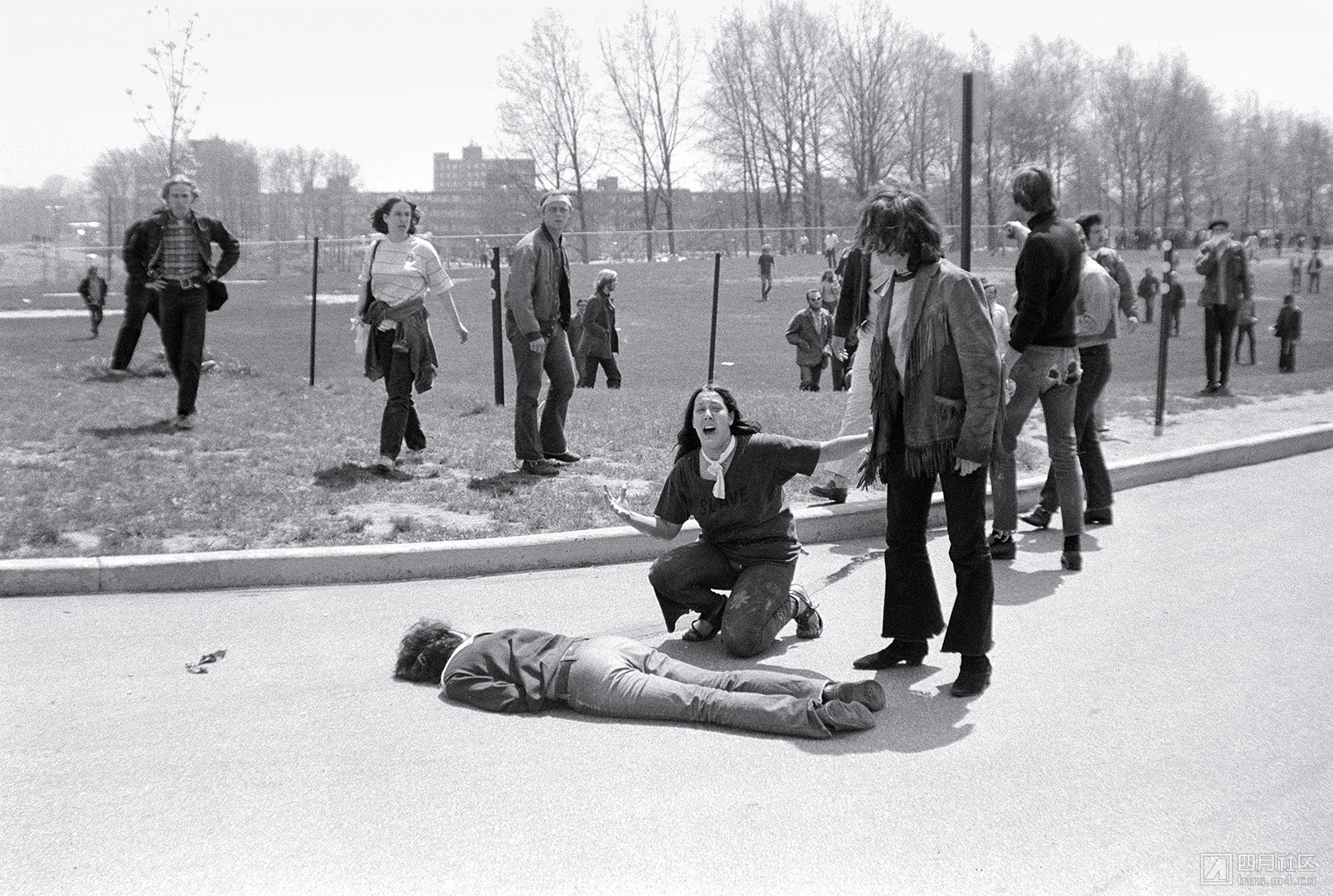

肯特州立大学枪击案

约翰•保罗•费罗

1970年

俄亥俄肯特州立大学的枪击持续了13秒。结束之后,4名学生死亡,9名学生受伤,一代人的天真与烂漫被无情地撕碎。抗议活动是为了响应全国各地的学生对于美军进入柬埔寨行动的不满。在肯特州立大学的校区,抗议者本以为周围被召集来的国民警卫队使用的是空爆弹。但是枪声停止之后,有学生躺倒在地,似乎东南亚的战争一下子来到了家门口。约翰•费罗是一名学生,也是个兼职新闻摄影师,他把这种感觉浓缩在一张照片中。他拍摄到玛丽•安•维奇奥失声痛哭,跪在已经没有呼吸的杰弗里•米勒身旁。费罗的照片被发送到美联社,出现在《纽约时报》的头版。之后获得了普利策奖,成为了一个欣欣向荣的国家中失落一代的标志。正如尼尔•杨受《生活》杂志中这篇照片文章启发写的一首歌《俄亥俄》中所说:“小锡兵和尼克松来了/我们最终还要靠自己/今年夏天我听到鼓声/四个人死在俄亥俄。”

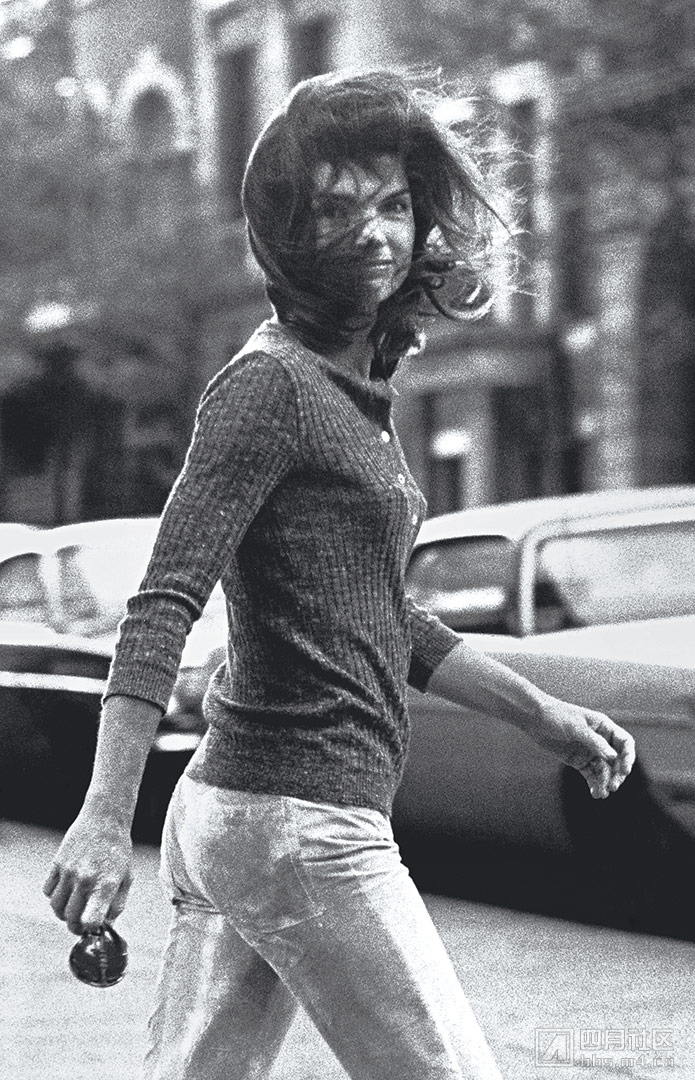

风中的杰奎琳

罗恩•加莱拉

1971年

人们对于杰奎琳•肯尼迪•奥纳西斯的消息永远不嫌多,这位年轻的寡妇是被暗杀总统的遗孀,后来嫁给希腊船业巨富。她是一名公众人物,受保镖的严密保护,因此成为追随她的那些摄影师们的主要目标。但是谁也比不上罗恩•加莱拉如此痴迷地捕捉前第一夫人的影像。作为早期自由职业的狗仔摄影师,加莱拉用跟踪和埋伏的方式开创了今天的自由摄影职业模式,拍摄了众多明星的照片,包括迈克尔•杰克逊、索菲亚•罗兰和马龙•白兰度。后者对加莱拉深恶痛绝,有一次打掉了他5颗牙齿。但是加莱拉还是最喜欢杰奎琳•奥纳西斯,简直可以用痴迷来形容。1971年10月,他发现她在纽约上东区的形迹之后,跳上一辆出租车跟随她。出租车司机按下喇叭,当奥纳西斯向这边张望时,加莱拉按下了快门。他回忆道:“我想他并不知道是我在拍照,所以还会面带笑容。”加莱拉自豪地说这张照片是“我的蒙娜丽莎”,它流露出未加提防的自然感,这是优秀明星街拍的关键所在。作家迈克尔•格罗斯说:“这是美国明星气质的标志性摄影作品,他创造了一种风格。”这张照片还尝试探索了新闻搜集与公众人物私人权利间模糊的界线。杰奎琳对于她所收到的关注颇为不满,两次把加莱拉告上法庭,最终拿到了禁止他拍摄自己家人的法令。但是他并不担心后继无人。

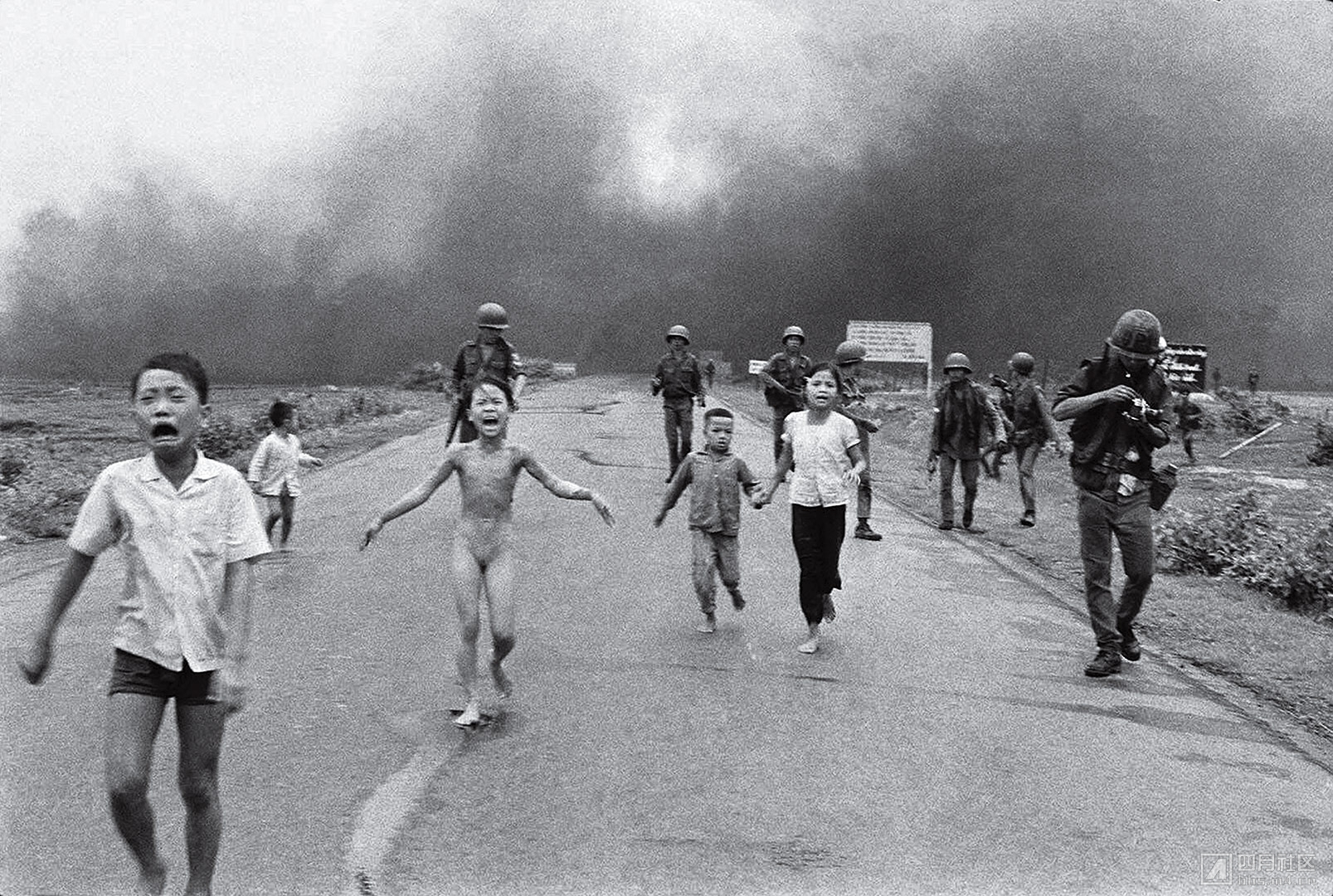

战争的恐怖

黄幼公

1972年

我们很少看到附带伤害和友军误伤的景象,但9岁的潘氏金福就是这样的遭遇。1972年6月8日,美联社摄影记者黄幼公正在壮庞郊外,位于西贡西北部大约25英里,南越空军在村庄上空错误投下一批燃烧弹。当这位越南籍摄影师拍摄村庄的惨状时,他看到几个孩子和士兵,其中有一个裸体女孩沿高速公路向他跑来。黄在想,她什么不穿衣服?之后意识到她被燃烧弹攻击。“我把大量的水淋到她身上,她一直在喊叫‘太热了!太热了!’”黄把金福送到医院后,得知她全身30%的皮肤三度烧伤,恐怕无法幸存。于是他在同事们的帮助下,把她转移到一家美军医疗机构,最终救下了她的性命。黄的这张照片具有毫不掩饰的惨烈效果,让人们看到战争所造成的伤害远大于其带来的好处。它还引发了全世界新闻编辑室中的争论,是否要发表一张裸体的照片。最终,包括《纽约时报》在内的出版商推翻了他们原有的政策。这张照片迅速成为越南战争暴行的速记,与马尔科姆•布朗的“僧侣自焚”和艾迪•亚当斯的“西贡处决”一起成为定义残忍军事冲突的影像记录。当理查德•尼克松总统询问这张照片是否伪造的时候,黄说:“我所记录的越南战争恐怖根本不需要伪装。”1973年,普利策评奖委员会把该奖项授予他。同年,美国从越南撤出驻军。

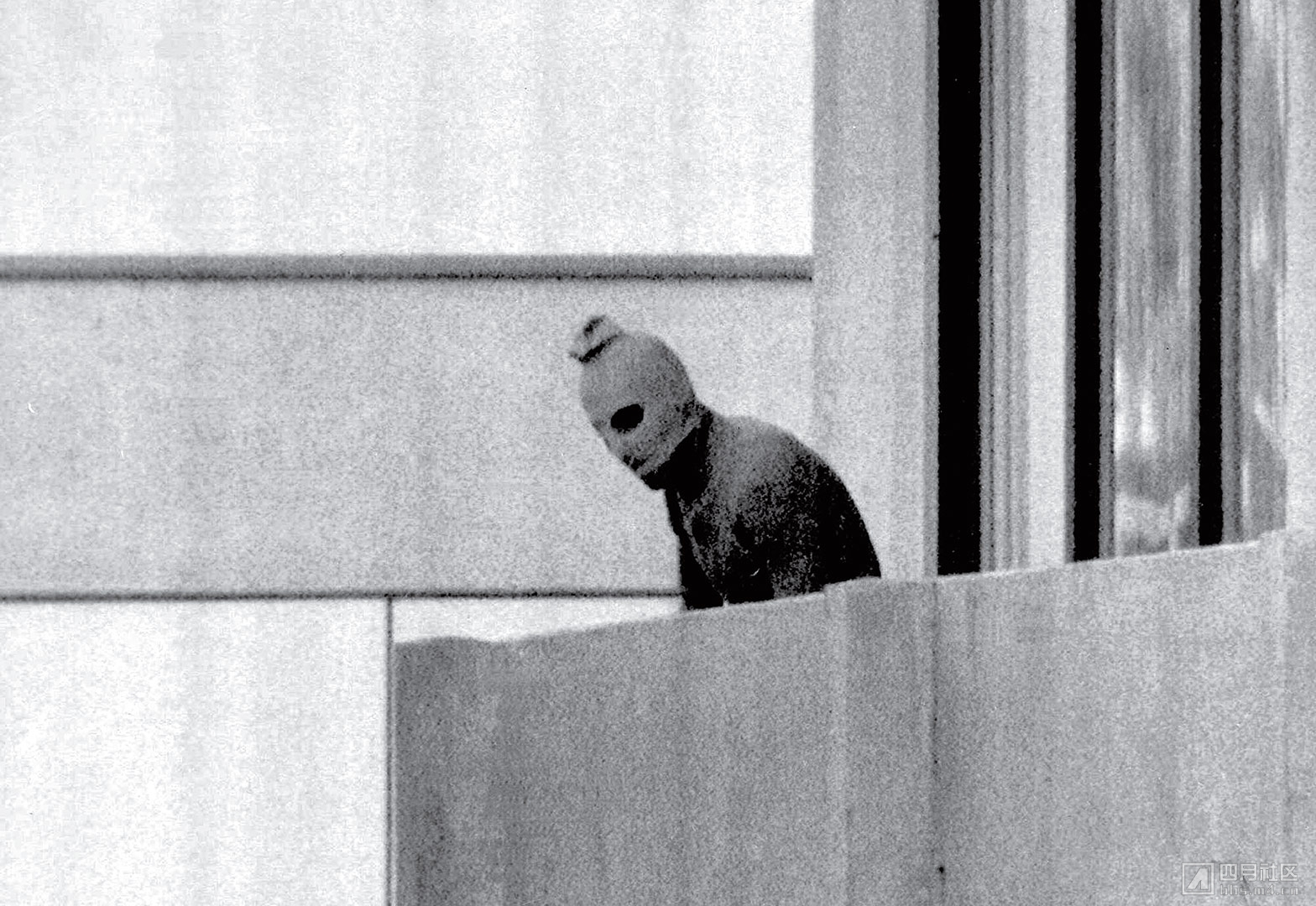

慕尼黑惨案

库尔特•斯特鲁普夫

1972年

奥运会崇尚人性的光辉。德国在1972年迎来奥运会,以此展现他们的竞技水平和民主制度,同时消除人们对1936年阿道夫•希特勒奥运会的坏印象。德国人说这次奥运会是“和平与欢乐的盛会”,以色列击剑运动员丹•阿龙说:“在柏林奥运会36年之后再次参加开幕式,是我一生最美好的记忆之一。”当地的安保措施并不严密,目的是维护一个和谐的气氛。不幸的是,这让巴勒斯坦恐怖组织“黑色九月”在9月5日可以轻易进入慕尼黑奥运村以色列运动员居住的公寓。恐怖分子携带着手榴弹和突击步枪,他们杀死了两名运动员,绑架了9名人质,要求释放被关押的234名同胞。持续了21个小时的对峙让全世界首次现场看到了恐怖组织的行径,9000万人收听了现场报道。在重重包围中,一名黑色九月恐怖分子走到公寓的阳台上。美联社摄影记者库尔特斯特鲁普夫拍到了这张恐怖的照片——一名没有面目的恐怖分子。当巴勒斯坦人试图逃离时,德国狙击手开始射击,巴勒斯坦人最终杀害了人质和一名警察。本已紧张的阿拉伯国家与以色列的关系,进一步恶化,这次事件导致了针对巴勒斯坦军事基地的报复行动。斯特鲁普夫照片上这个幽灵般的人物、头罩上割出的双眼形状,让我们冷静地意识到,当世界不再安全时,我们是多么的渺小。

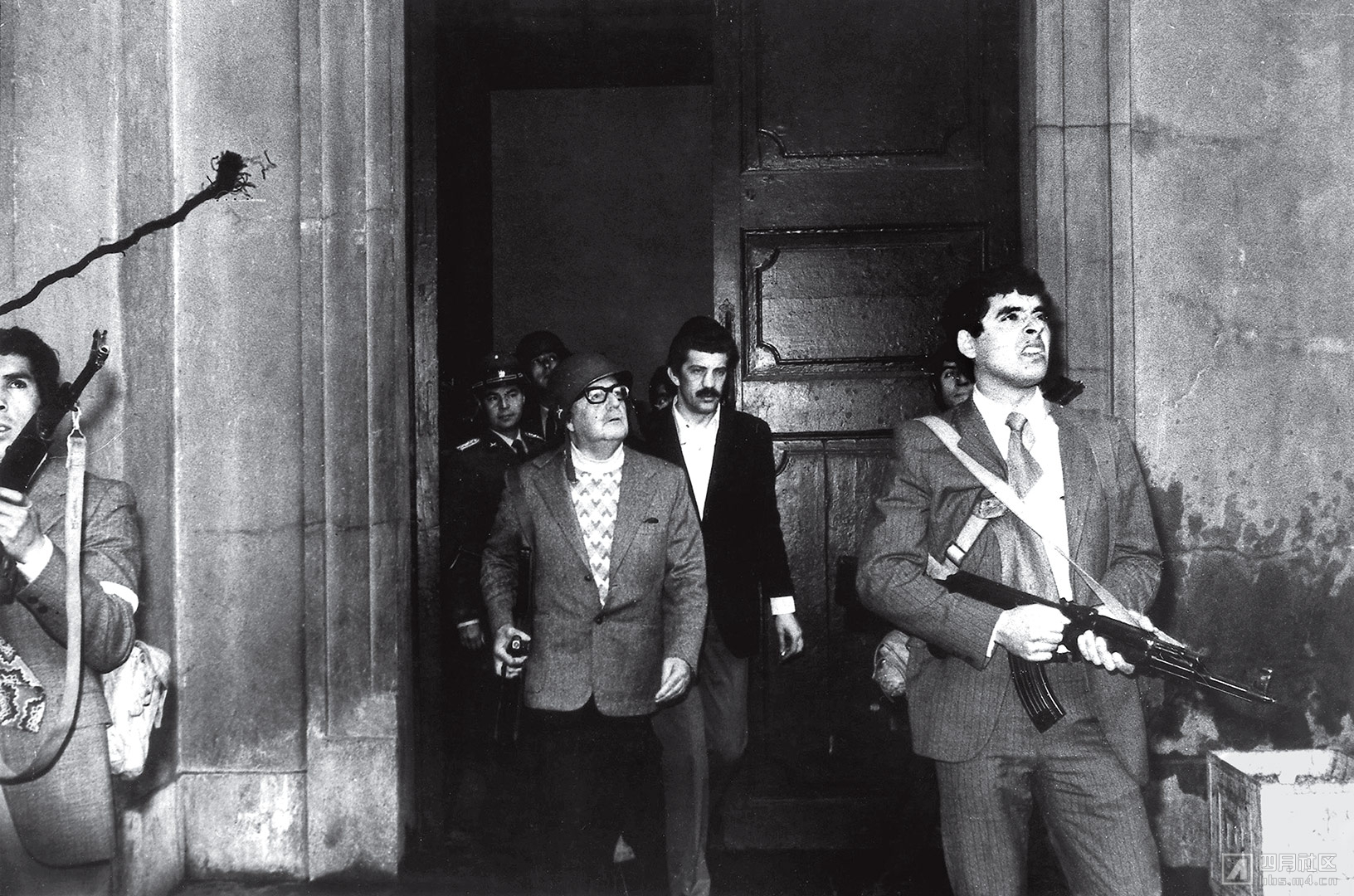

阿连德的最后一战

路易斯•奥兰多•拉各斯

1973年

萨尔瓦多•阿连德是第一位民主选举的马克思主义总统,在1970年当选之后,他立志要改变智利。他把美国企业国有化、让土地成为集体所有制、冻结物价、提升工资、增发货币提供改革所需资金。但国内经济一蹶不振,通货膨胀带来了不安定的局势。1973年8月底,阿连德委任奥古斯托•皮诺切特为总司令。18年之后,这位保守派将军发动了政变。阿连德拒绝离开智利,他手持AK-47冲锋枪,身边只有最忠诚的卫兵守护。他在国家电台发表最后的演说,广播背景可以听到枪声。当圣地亚哥的总统府遭到炮击时,阿连德的官方摄影师路易斯•奥兰多•拉各斯拍到了他最后一个镜头。不久阿连德就自杀身亡,当然,几十年来都有人猜测他是被政变士兵击毙。由于担心自身的安危,拉各斯逃离智利。在皮诺切特将近17年的统治中,4万名智利人遭到审讯、施刑、杀害和失踪。拉各斯的照片发表时并未署名,它赢得了1973年世界媒体年度照片的奖项。人们把这张照片当作阿连德不朽的象征,他宁愿选择死亡也不愿被羞辱。2007年,拉各斯死后,人们才知道摄影师的真实身份。

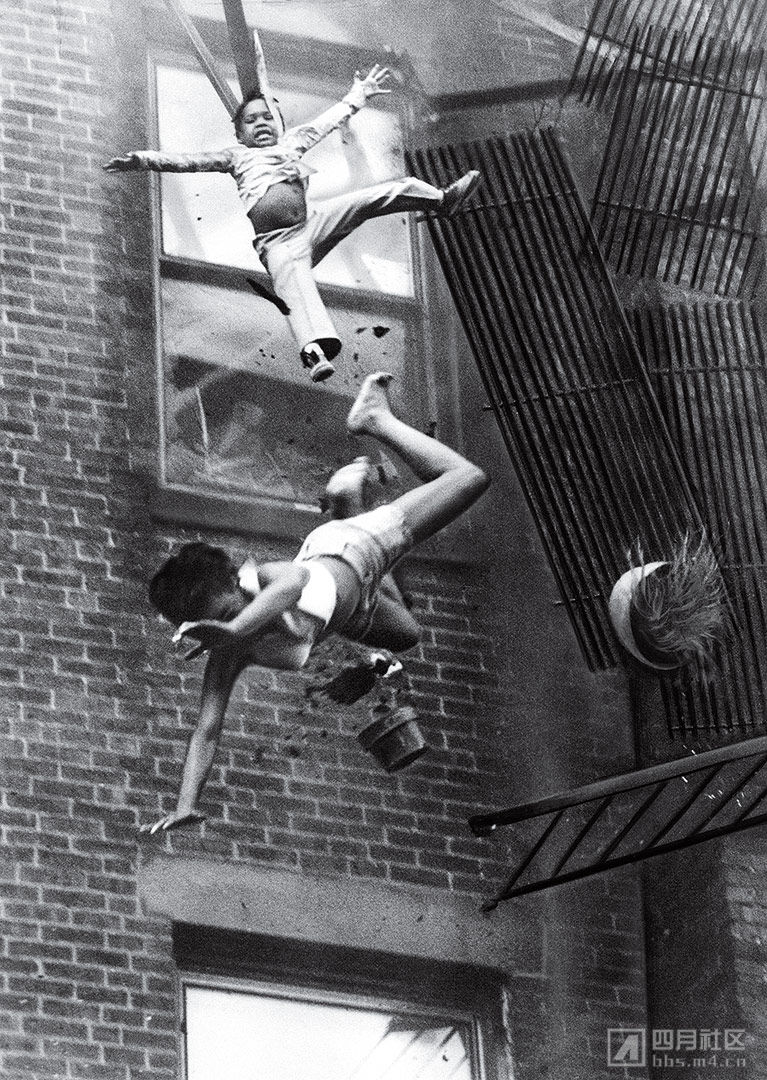

火灾逃生者坠楼

史丹利•弗门

1975年

1975年7月22日,史丹利•弗门在《美国波士顿先驱报》任职,他接到一个电话,说马尔伯勒大街发生火灾。他立即赶往现场,看到一个女人和一个孩子在五楼的防火梯上。一位消防员正准备救援,弗门觉得他拍摄到的不过是一次正常的营救场景。“突然,防火梯塌了。”19岁的黛安•布莱恩特和她两岁的教女蒂亚尔•琼斯从空中坠落。“他们坠落的镜头被我拍下来,之后我转过身,这才明白究竟发生了什么。我不想看到他们跌落到地面的样子。我依然记得自己当时混身颤抖。”布莱恩特立即死亡,她的身体让她的教女得以缓冲,最终幸存。尽管这起事件与每天充斥在地方新闻报道中的悲剧并无二致,但弗门的照片与众不同。他使用的是马达驱动镜头,可以捕捉到这个恐怖的瞬间,小蒂亚尔脸上的表情清晰可见。这张照片为弗门赢得了普利策奖,并促使全国各地市政府实施更严格的火灾逃生条例。它带来的影响还出现在伦理层面。很多读者反对出版弗门的照片,对于是否应该发表令人过于不安的图片,至今依然存在争论。

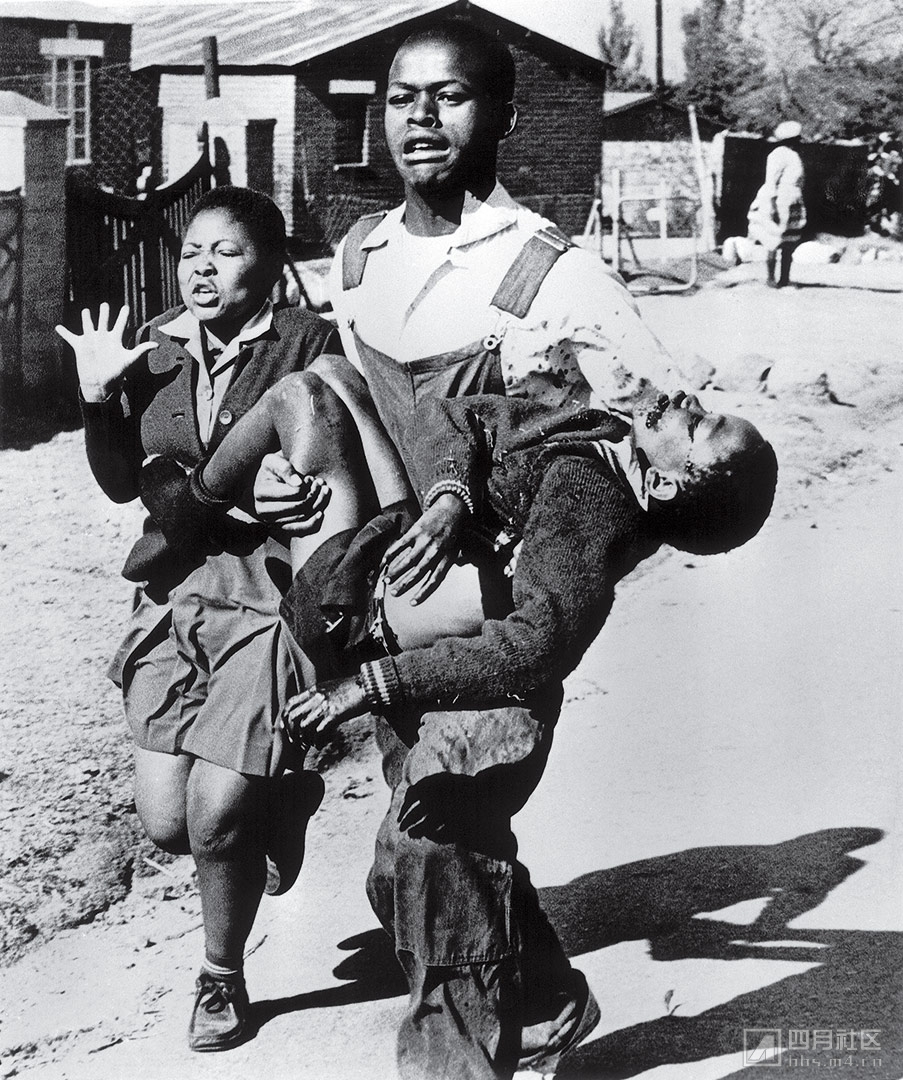

索韦托起义

萨姆•恩奇马

1976年

身处南非以外的人在1976年6月16日前很少关注其种族隔离制度。那一天,数千名索韦托学生抗议学校中强制开设南非荷兰语课程。抗议过程中,不断有来自其他学校的年轻人加入,其中就包括13岁的学生海克特•彼得森。接着他们与警方发生冲突,警方发射了催泪瓦斯,学生们用石块还击,警方开始向人群射击。萨姆•恩奇马来自约翰内斯堡黑人社区的《世界报》,他在现场做报道,他回忆道:“起初,我匆忙跑离现场。但后来,我又跑回去。”恩奇马就在那时看到了彼得森在枪林弹雨中倒下。他不断地拍照片,高中学生姆布伊萨•马库布抱起已经没有呼吸的男孩,与彼得森的姐姐安托瓦内特•锡霍尔一起跑开。一场和平的抗议活动以暴力收场,整个南非有数百人丧生。总理约翰•福斯特说:“政府绝不会与恐吓妥协。”但是武力统治无法阻挡恩奇马所拍摄的彼得森照片,它讲述的是南非政府杀害自己人民的故事。照片的发表让恩奇马不得不在铺天盖地的死亡威胁中躲起来,但照片的威力再明显不过了。整个世界已经无法对种族隔离制度视而不见,一张照片播下的国际社会反对的种子,最终推翻的种族主义制度。

Earthrise

William Anders, NASA

1968

It’s never easy to identify the moment a hinge turns in history. When it comes to humanity’s first true grasp of the beauty, fragility and loneliness of our world, however, we know the precise instant. It was on December 24, 1968, exactly 75 hours, 48 minutes and 41 seconds after the Apollo 8 spacecraft lifted off from Cape Canaveral en route to becoming the first manned mission to orbit the moon. Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve of what had been a bloody, war-torn year for America. At the beginning of the fourth of 10 orbits, their spacecraft was emerging from the far side of the moon when a view of the blue-white planet filled one of the hatch windows. “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders exclaimed. He snapped a picture—in black and white. Lovell scrambled to find a color canister. “Well, I think we missed it,” Anders said. Lovell looked through windows three and four. “Hey, I got it right here!” he exclaimed. A weightless Anders shot to where Lovell was floating and fired his Hasselblad. “You got it?” Lovell asked. “Yep,” Anders answered. The image—our first full-color view of our planet from off of it—helped to launch the environmental movement. And, just as important, it helped human beings recognize that in a cold and punishing cosmos, we’ve got it pretty good.

Albino Boy, Biafra

Don McCullin

1969

Few remember Biafra, the tiny western African nation that split off from southern Nigeria in 1967 and was retaken less than three years later. Much of the world learned of the enormity of that brief struggle through images of the mass starvation and disease that took the lives of possibly millions. None proved as powerful as British war photographer Don McCullin’s picture of a 9-year-old albino child. “To be a starving Biafran orphan was to be in a most pitiable situation, but to be a starving albino Biafran was to be in a position beyond description,” McCullin wrote. “Dying of starvation, he was still among his peers an object of ostracism, ridicule and insult.” This photo profoundly influenced public opinion, pressured governments to take action, and led to massive airlifts of food, medicine and weapons. McCullin hoped that such stark images would be able to “break the hearts and spirits of secure people.” While public attention eventually shifted, McCullin’s work left a lasting legacy: he and other witnesses of the conflict inspired the launch of Doctors Without Borders, which delivers emergency medical support to those suffering from war, epidemics and disasters.

A Man on the Moon

Neil Armstrong, NASA

1969

Somewhere in the Sea of Tranquillity, the little depression in which Buzz Aldrin stood on the evening of July 20, 1969, is still there—one of billions of pits and craters and pockmarks on the moon’s ancient surface. But it may not be the astronaut’s most indelible mark.

Aldrin never cared for being the second man on the moon—to come so far and miss the epochal first-man designation Neil Armstrong earned by a mere matter of inches and minutes. But Aldrin earned a different kind of immortality. Since it was Armstrong who was carrying the crew’s 70-millimeter Hasselblad, he took all of the pictures—meaning the only moon man earthlings would see clearly would be the one who took the second steps. That this image endured the way it has was not likely. It has none of the action of the shots of Aldrin climbing down the ladder of the lunar module, none of the patriotic resonance of his saluting the American flag. He’s just standing in place, a small, fragile man on a distant world—a world that would be happy to kill him if he removed so much as a single article of his exceedingly complex clothing. His arm is bent awkwardly—perhaps, he has speculated, because he was glancing at the checklist on his wrist. And Armstrong, looking even smaller and more spectral, is reflected in his visor. It’s a picture that in some ways did everything wrong if it was striving for heroism. As a result, it did everything right.

Kent State Shootings

John Paul Filo

1970

The shooting at Kent State University in Ohio lasted 13 seconds. When it was over, four students were dead, nine were wounded, and the innocence of a generation was shattered. The demonstrators were part of a national wave of student discontent spurred by the new presence of U.S. troops in Cambodia. At the Kent State Commons, protesters assumed that the National Guard troops that had been called to contain the crowds were firing blanks. But when the shooting stopped and students lay dead, it seemed that the war in Southeast Asia had come home. John Filo, a student and part-time news photographer, distilled that feeling into a single image when he captured Mary Ann Vecchio crying out and kneeling over a fatally wounded Jeffrey Miller. Filo’s photograph was put out on the AP wire and printed on the front page of the New York Times. It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and has since become the visual symbol of a hopeful nation’s lost youth. As Neil Young wrote in the song “Ohio,” inspired by a LIFE story featuring Filo’s images, “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming/ We’re finally on our own/ This summer I hear the drumming/ Four dead in Ohio.”

Windblown Jackie

Ron Galella

1971

People simply could not get enough of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the beautiful young widow of the slain President who married a fabulously wealthy Greek shipping tycoon. She was a public figure with a tightly guarded private life, which made her a prime target for the photographers who followed wherever she went. And none was as devoted to capturing the former First Lady as Ron Galella. One of the original freewheeling celebrity shooters, Galella created the model for today’s paparazzi with a follow-and-ambush style that ensnared everyone from Michael Jackson and Sophia Loren to Marlon Brando, who so resented Galella’s attention that he knocked out five of the photographer’s teeth. But Galella’s favorite subject was Jackie O., whom he shot to the point of obsession. It was Galella’s relentless fixation that led him to hop in a taxi and trail Onassis after he spotted her on New York City’s Upper East Side in October 1971. The driver honked his horn, and Galella clicked his shutter just as Onassis turned to look in his direction. “I don’t think she knew it was me,” he recalled. “That’s why she smiled a little.” The picture, which Galella proudly called “my Mona Lisa,” exudes the unguarded spontaneity that marks a great celebrity photo. “It was the iconic photograph of the American celebrity aristocracy, and it created a genre,” says the writer Michael Gross. The image also tested the blurry line between newsgathering and a public figure’s personal rights. Jackie, who resented the constant attention, twice dragged Galella to court and eventually got him banned from photographing her family. No shortage of others followed in his wake.

The Terror of War

Nick Ut

1972

The faces of collateral damage and friendly fire are generally not seen. This was not the case with 9-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc. On June 8, 1972, Associated Press photographer Nick Ut was outside Trang Bang, about 25 miles northwest of Saigon, when the South Vietnamese air force mistakenly dropped a load of napalm on the village. As the Vietnamese photographer took pictures of the carnage, he saw a group of children and soldiers along with a screaming naked girl running up the highway toward him. Ut wondered, Why doesn’t she have clothes? He then realized that she had been hit by napalm. “I took a lot of water and poured it on her body. She was screaming, ‘Too hot! Too hot!’” Ut took Kim Phuc to a hospital, where he learned that she might not survive the third-degree burns covering 30 percent of her body. So with the help of colleagues he got her transferred to an American facility for treatment that saved her life. Ut’s photo of the raw impact of conflict underscored that the war was doing more harm than good. It also sparked newsroom debates about running a photo with nudity, pushing many publications, including the New York Times, to override their policies. The photo quickly became a cultural shorthand for the atrocities of the Vietnam War and joined Malcolm Browne’s Burning Monk and Eddie Adams’ Saigon Execution as defining images of that brutal conflict. When President Richard Nixon wondered if the photo was fake, Ut commented, “The horror of the Vietnam War recorded by me did not have to be fixed.” In 1973 the Pulitzer committee agreed and awarded him its prize. That same year, America’s involvement in the war ended.

Munich Massacre

Kurt Strumpf

1972

The Olympics celebrate the best of humanity, and in 1972 Germany welcomed the Games to exalt its athletes, tout its democracy and purge the stench of Adolf Hitler’s 1936 Games. The Germans called it “the Games of peace and joy,” and as Israeli fencer Dan Alon recalled, “Taking part in the opening ceremony, only 36 years after Berlin, was one of the most beautiful moments in my life.” Security was lax so as to project the feeling of harmony. Unfortunately, this made it easy on September 5 for eight members of the Palestinian terrorist group Black September to raid the Munich Olympic Village building housing Israeli Olympians. Armed with grenades and assault rifles, the terrorists killed two team members, took nine hostage and demanded the release of 234 of their jailed compatriots. The 21-hour hostage standoff presented the world with its first live window on terrorism, and 900 million people tuned in. During the siege, one of the Black Septemberists made his way out onto the apartment’s balcony. As he did, Associated Press photographer Kurt Strumpf froze this haunting image, the faceless look of terror. As the Palestinians attempted to flee, German snipers tried to take them out, and the Palestinians killed the hostages and a policeman. The already fraught Arab-Israeli relationship became even more so, and the siege led to retaliatory attacks on Palestinian bases. Strumpf’s photo of that specter with cut-out eyes is a sobering reminder of how we were all diminished when the world realized that nothing was secure.

Allende's Last Stand

Luis Orlando Lagos

1973

Salvador Allende was the first democratically elected Marxist head of state, and he assumed the presidency of Chile in 1970 with a mandate to transform the country. He nationalized U.S.-owned companies, turned estates into cooperatives, froze prices, increased wages and churned out money to bankroll the changes. But the economy faltered, inflation soared, and unrest grew. In late August 1973, Allende appointed Augusto Pinochet as commander of the army. Eighteen days later, the conservative general orchestrated a coup. Allende refused to leave. Armed with an AK-47 and protected only by loyal guards at his side, he broadcast his final address on the radio, the sound of gunfire audible in the background. As Santiago’s presidential palace was bombarded, Luis Orlando Lagos, Allende’s official photographer, captured one of his final moments. Not long after, Allende committed suicide—though for decades many believed he was killed by the advancing troops. Fearing for his own life, Lagos fled. During Pinochet’s nearly 17-year rule, 40,000 Chileans were interrogated, tortured, killed or disappeared. Lagos’ picture appeared anonymously. It won the 1973 World Press Photo of the Year award and became revered as an image that immortalized Allende as a hero who gladly chose death over dishonor. It was only after Lagos’ death in 2007 that people learned the photographer’s identity.

Fire Escape Collapse

Stanley Forman

1975

Stanley Forman was working for the Boston Herald American on July 22, 1975, when he got a call about a fire on Marlborough Street. He raced over in time to see a woman and child on a fifth-floor fire escape. A fireman had set out to help them, and Forman figured he was shooting another routine rescue. “Suddenly the fire escape gave way,” he recalled, and Diana Bryant, 19, and her goddaughter Tiare Jones, 2, were swimming through the air. “I was shooting pictures as they were falling—then I turned away. It dawned on me what was happening, and I didn’t want to see them hit the ground. I can still remember turning around and shaking.” Bryant died from the fall, her body cushioning the blow for her goddaughter, who survived. While the event was no different from the routine tragedies that fill the local news, Forman’s picture of it was. Using a motor-drive camera, Forman was able to freeze the horrible tumbling moment down to the expression on young Tiare’s face. The photo earned Forman the Pulitzer Prize and led municipalities around the country to enact tougher fire-escape-safety codes. But its lasting legacy is as much ethical as temporal. Many readers objected to the publication of Forman’s picture, and it remains a case study in the debate over when disturbing images are worth sharing.

Soweto Uprising

Sam Nzima

1976

Few outside South Africa paid much attention to apartheid before June 16, 1976, when several thousand Soweto students set out to protest the introduction of mandatory Afrikaans-language instruction in their township schools. Along the way they gathered youngsters from other schools, including a 13-year-old student named Hector Pieterson. Skirmishes started to break out with the police, and at one point officers fired tear gas. When students hurled stones, the police shot real bullets into the crowd. “At first, I ran away from the scene,” recalled Sam Nzima, who was covering the protests for the World, the paper that was the house organ of black Johannesburg. “But then, after recovering myself, I went back.” That is when Nzima says he spotted Pieterson fall down as gunfire showered above. He kept taking pictures as terrified high schooler Mbuyisa Makhubu picked up the lifeless boy and ran with Pieterson’s sister, Antoinette Sithole. What began as a peaceful protest soon turned into a violent uprising, claiming hundreds of lives across South Africa. Prime Minister John Vorster warned, “This government will not be intimidated.” But the armed rulers were powerless against Nzima’s photo of Pieterson, which showed how the South African regime killed its own people. The picture’s publication forced Nzima into hiding amid death threats, but its effect could not have been more visible. Suddenly the world could no longer ignore apartheid. The seeds of international opposition that would eventually topple the racist system had been planted by a photograph.

|

|