本帖最后由 满仓 于 2010-5-29 23:41 编辑

【中文标题】中国的包办再婚

【原文标题】China’s Arranged Remarriages

【登载媒体】纽约时报

【原文作者】BROOK LARMER

【原文链接】http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09widows-t.html?pagewanted=1

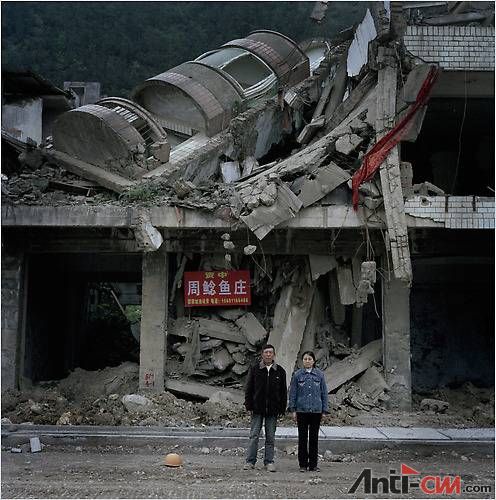

左:杨春和薛颖抱着他们的儿子张瑞军。(译者注:原文如此。)右:一块俯视北川的石碑上写道:“沉痛悼念512遇难同胞”。

新婚的人们非常幸福,你看不到吗?

在他们位于四川省农村的家里,墙上贴满了海报尺寸的结婚照。照片里,这对夫妇无忧无虑地在绿色的原野中嬉戏,他们在秋天落叶的背景幕墙下相互依偎,在蔚蓝天空下的海边拥抱。在每一个经过柔光处理的照片中,新娘——25岁的薛颖、曾经的服装店主——穿着无带的白色婚纱,戴着闪闪发光的头饰。新郎——37岁的杨春、公交车司机——穿着白色的燕尾服,戴着领结。他那些参差不齐、满是烟渍的牙齿在照片中变得整齐又洁白。

秋天落叶背景的那张照片有一个语义混乱的英文标题“Romandic Story”。在热带海滩上,薛靠在杨的怀抱中,面纱随风飘动,杨的脸上绽放出幸福的微笑。上边也有一个无法看懂的英文标题“I Make a Wish With U.”。

去年秋天的一个下午,杨和薛邀请我到家里做客。7月份刚刚完婚的这对夫妇很高兴地向我展示他们幸福的新婚物品。这些幻景都是一个当地的摄影工作室为他们制作的虚假、甜美的回忆。数字处理点亮了他们的笑容,抹去了瑕疵,给他们的婚姻涂上了厚厚一层甜蜜的浪漫。至于杨和薛生活在中国西南四川省的山区,以及他们从未到过海边这一事实其实并不重要。这些照片还有更重要的意义——掩盖那些痛苦得难以承受的过去。

在过去的两年中,杨和薛用各自的方式挣扎着摆脱2008年5月12日的阴影。那天下午2点28分,一场7.9级的地震袭击了四川。在短短80秒的时间里,他们的世界被彻底毁灭了。杨的妻子,一个小卖部的主人,是被埋葬在他们家乡北川的废墟中15000多名遇难者之一。他们的独子,一个7岁的男孩,在曲善小学倒塌时被掩埋。这个地区其它数千所学校建筑物也一样,像手风琴一样接连地倒塌。几百码之外,薛在自己的家倒塌的几秒钟之前爬了出来,之后发现她的未婚夫被山体滑坡掩埋。

四川地震所释放的破坏力如此令人震惊,以至于就像1月份的海地地震一样,其恐怖程度可以用一系列统计数字来表示:87000多人死亡或失踪,将近40万人受伤,500万人无家可归。北川坐落于四川这个山区地带的河流转弯处,震中向北60英里。那里景色优美,但由于其处于两条地震带的交汇处,这里的地理条件极为不稳定,以至于官方多年来就在考虑推平县城,迁移到其它地方。地震在一瞬间完成了这个工作,县城里80%的建筑物被摧毁,22000居民中的三分之二死亡,其中大多数是羌族居民。

两年之后,北川变成了一个被铁丝网和中国军队包围起来的鬼城。大部分幸存者依然住在临时房屋中,这种蓝色屋顶的铝制建筑物点缀着地震受灾区。一些人,比如杨和薛,搬到了安昌,那里是临时县政府所在地,正式的政府机构将会设置在永昌,即“永远繁荣”之意。这个地方位于北川向南15英里的一个冲击平原上,它是中国声称将用于救灾和重建的400百亿美元中的一小部分。来自四川地区的贫穷农民工为中国东部地区经济发展做出了重大的贡献,而现在,四川在接受中央政府的馈赠,从房屋、道路和基础设施到一种新兴的产业“震区旅游”。

然而,笼罩在实物重建上的是另一个问题:如何重建社会?中国对此的一个回答是让悲伤的男人和女人配对,这种“速成家庭”可以帮助实现社会和经济的稳定。在西方人看来,对婚姻的选择要基于个人对爱情和浪漫的观点,或者至少我们认为应该如此。但是在四川,婚姻最首要的任务是组建家庭和社区。地震所摧毁的家庭并不仅仅是个人的悲剧,而且造成了社会根基的裂缝。

哄骗那些地震幸存者们再婚已经成为了一种社会责任。一些身份可疑的志愿者们纷纷加入媒人队伍,从以前的亲戚到负责照看四川农村地区每一个家庭的共产党“工作组”,在他们身后的是中国政府。这个国家长久以来被认为擅于干涉人民的大部分私人生活,包括生育权力。现在,它热切地鼓励——在有些场合甚至是安排——所谓的冷冰冰的“家庭重建计划”。

2008年底,地震发生之后不到8个月的时间里,北川有614名幸存者已经再婚。这些数字来源于当地一名民政官员王鸿发。(尽管没有公开发布,四川地震灾区全部的再婚人数估计已经达到数千人。)如此众多的地震幸存者再婚并不是一个令人吃惊的事实,但是这其中的绝大部分都是寡妇与鳏夫的结合,两个幸存者努力奋斗,为将来的生活奠定一个坚实的基础。

杨和薛继续摸索着他们生活的方向。一天晚上,我去他们家里做客,厨房里冒出的浓烟让房间里充满了辣椒酱那种辛辣刺鼻的味道。杨穿着蓝色的围裙,从厨房里探出头来。眼泪从他有些不好意思的眼神中流出来,但是他的脸上带着笑容。他说:“回锅肉。”这是四川人的拿手菜。薛坐在椅子上,对我微笑,手里拿着一盒子鞋垫。她在给这些鞋垫刺绣,这可以使杨的鞋子在整天开车时更舒服,也更耐穿。她的母亲和哥哥也在家里做客,杨终于有机会再次给家里人做饭了。几分钟之后,杨抱着一堆盘子从厨房里出来,有鸡爪、芝麻酱凉面、牛肉和土豆炖回锅肉,这些菜都将佐以白酒下肚。杨把他的新家庭成员召集到桌旁,露出黄板牙宣布“开饭”。

“嘿,你刚刚跑到哪里去了?”

这是杨的第一任妻子罗雪梅在地震发生几小时前发出的最后一条短信,现在它还保存在杨的手机里。那天早晨,杨不想吵醒熟睡中的妻子和儿子,悄悄离开了北川的家。他回到老家片口村,为自己的小生意采购一些蘑菇和蜂蜜。

地震发生的4天之后,这条短信是杨的唯一寄托,他花了两天时间爬过40英里被滑坡破坏得面目全非的山路回到北川。他跑遍了医院、体育馆和灾民营地,希望能找到幸存的妻子和儿子。他掀开数十具从他儿子学校废墟中扒出的尸体上的遮盖物。杨和我说:“这太难以承受了。”他倒在废墟上,失声痛哭:“老天,你太残忍了!”

杨回到北川的那一天,有1000多人在废墟上攀爬,所有人都哭喊着家人的名字。薛也是其中之一。她认识杨的妻子,在瓷砖工厂完成定额工作之后,她也在市中心卖衣服。薛在瓦砾中寻找她35岁的未婚夫,她现在开始怀疑死是否真的没有活着好。她已经在这片废墟上寻找了4天,徒手翻弄着瓦砾。她的父母和哥哥已经确定无法找到了(在第5天的时候,他们被发现还活着。),她心里其实很清楚,山体滑坡把她未婚夫的家埋在100英尺深的泥土和水泥下,他必定无法生还了。她不再继续挖了。她的爱人死了,同样死去的还有他们组建家庭的美梦。

北川变成了一个巨大的坟墓,数千具尸体被埋在废墟下边。接下来的几个月,薛住在当地体育馆外边政府安置的帐篷里,吃饼干和速食面。她无法入睡,因为始终没有看到未婚夫的尸体。杨回到片口父母的家中,陷入一种有自杀倾向的呆滞状态。他瘦了30磅。他几乎没有睡觉,每次闭上眼睛,他就会看到自己的妻子和儿子在废墟上蹒跚,等着自己去救他们。杨没有和任何人提起过这场悲剧。他说:“我不能和父母还有其它亲戚诉说这些,他们也遭受了巨大的损失。所以我把一切都藏在心里,整天在想我为什么还要继续活下去。”

杨的家人认为,把他从危险的边缘拉回来的唯一方法就是让他尽快再婚。杨回忆:“我的父母、姐姐、妹妹都给我压力,让我继续前进。我的大舅子号召一些朋友帮助我物色对象,甚至我的岳母,在地震发生后一个月,就敦促我尽快找人结婚。”他还接到了共产党在当地宣传部的电话。33岁的冯翔是这个部的副主任,他的儿子和杨的儿子一样,也在曲善小学倒塌后丧生,他后来自杀了。冯的同事鼓励杨开始一个新的生活,并且表示愿意提供一切可能的帮助。

然而,在杨看来,再婚是一种可耻的念头,这等于背叛他的妻子和儿子。杨不愿意在与任何人联络,他一心想逃避。所以,当他一个远在河北省的姑姑召唤他的时候,杨痛快地离开了四川。在家乡饭和中草药的结合治疗下,他的姑姑渐渐让他回到了现实生活中。

邓群华原来的职业是裁缝。在地震中失去了她的家庭和事业之后,她开始提供婚姻介绍服务。

婚姻介绍人的木头桌子上摆着两个厚厚的文件夹——一个是男人名单,另一个是女人名单。文件中一行行的人名全都是邓群华娟秀的笔迹。她原来的职业是裁缝,在地震中失去了她的家庭和事业之后,她开始提供婚姻介绍服务。邓的名单中,每一个名字后边都标着客户的年龄(从22岁到78岁),还有身高、教育程度、职业和对对方的要求。除此之外,还有一个更敏感的信息——两个字的正式用语跟在绝大部分的名字后边:丧偶。邓的手指滑过一个个的名字说:“这都是地震遗留下来的寡妇和鳏夫,他们中的大部分都没有过多的要求,他们只不过想要回部分失去的东西。”

邓自然而然地进入了这个充满孤独心灵的新市场。由于震后的创伤,她与丈夫离婚,恢复了单身的状态。这位喜爱社交的北川人对周围产生了发自内心的怜悯,于是她开始收集单身人士名单。女性可以免费加入她的名单,男性需要支付200元人民币(30美元),以换取无限次数的对象介绍,直到双方成功结合。邓的办事处设在北川以南10英里的安昌,但是当地还有其它婚姻介绍机构,甚至当地政府也提供这种服务。所以邓进入山区,在道路两边的岩石、柱子和农民家的墙上贴上征婚名单的复印件。

目前为止邓已经成功介绍了100多对地震遗留下来的寡妇和鳏夫成婚。她说,做这些事情让她感觉自己不是一个商人,而更像一个社会工作者。邓说:“地震幸存者一般都觉得不应该这么快就去找一个新的配偶,但是当他们看到别人有一个温暖的家庭,自己也会想要了。”

然而,找到一个合适的避风港并不是件容易的事,悲痛和心灵创伤依然占据了地震幸存者的心智。新伙伴必须接受对方原先的生活:债务、有争议的财产、姻亲、长辈,以及最重要的——孩子。在邓的名单中,所有人对心仪配偶最渴望的要求不是金钱、相貌、性格和教育程度,而是“无负担”。那些背负沉重负担的人——尤其是带孩子的中年妇女——留在名单上的时间最久,年轻人和老年人相对要幸运得多。即使如此,一些被仓促安排的“震后婚姻”也已经分崩离析了。据邓的回忆,有一对夫妇在结婚12天后就宣告离婚,“这算是一个纪录了”。

去年年初,当地的一名医生进入了邓的名单中。这个男人在地震时碰巧幸免遇难,在医院倒塌时他刚好外出就诊。他的妻子没有那么幸运。营救人员找到她的尸体的时候,发现她紧紧拉住一个婴儿,这不是她的孩子,但她明显在试图救出这个婴儿。邓是这样记录下这个医生的个人信息的:57岁,丧偶,英俊……

几个星期之后,邓和她的新客户一起来到他妻子遇难的现场。他焚香纪念自己的爱人,在他失声痛哭时,她给了他一些安慰。医生和介绍人互相凝视对方,他们产生了感情,并且很快进入到谈婚论嫁的阶段。邓知道,她的未婚夫依然处于悲痛之中,灾难给了他太多的伤害。但是当他提出停止婚约的时候,还是让她大吃一惊。她今年42岁,比他年轻15岁,但他还是认为她岁数太大了。尽管他有一个已经成年的儿子,他还是想再寻找另外一个家庭。于是邓别无选择,只好继续履行他的专业职责,毕竟医生已经支付了30美元的介绍费。她现在贴在农民房屋墙上的征婚名单复印件上,加上了医生的最后一条要求:“30岁以下女性,可以接受自己的子女。”

对于北川南部临时安置点22号房间的一对老人来说,子女并不是一个问题。56岁的临时工刘寅虎在山坡上的一个建筑废墟上整整挖了两天,试图寻找他妻子的尸体。赵永兰,一个圆脸的农民,在地震中几乎失去了所有的东西:她的丈夫、两个已经长大的孩子、她的姐姐、大伯和她的房子。54岁的赵从小就与刘相识。当刘的姐姐在地震几个月之后重新介绍他们认识时,赵依然沉浸在悲痛中。刘说:“整整一个月,我每天都在安慰她。我不停地说:‘你还是应该找个人来照顾自己,你太年轻了,不能失去希望。’”

一切重新开始。刘寅虎说,他花了一个月的时间来说服极度悲伤的赵永兰嫁给他。

赵最终心软了。2009年1月,他们在安置点的一个餐厅里举办了婚礼,邀请了八桌的亲戚和朋友。一年之后,我和这对夫妻还有赵84岁的老母亲一起在这家餐厅吃饭。在堆满野生蘑菇和孜然味猪肋骨的餐桌上,刘向我讲述了他们恋爱的故事。赵涨红了脸,开玩笑地用拳头打他。赵的母亲无意中说出,这对夫妇实际上是第一代表亲。刘说:“我们知道这不对,但是我们的年龄已经不会再有孩子了,所以有什么关系呢?”

去年春节是中国人哀悼逝者的日子,赵加入了前往北川的人群,她的家人的尸体依然被埋在废墟下面。在靠近县城边缘铁丝网的地方,她崩溃了,摔倒在地,无法站起。她揪着耳朵控制自己不要哭出来,她说:“我实在太害怕了。”刘把手搭在她的肩膀上,拿给她一张纸巾擦眼睛。赵说,她将会鼓起勇气再次回到那里。她看着刘:“我自己还是不敢去,但是有他的陪伴,我一定会回到那里的。”

杨和薛,那位公交车司机和前服装店主,第一次见面是在2009年初,一位他们共同的朋友邀请他们去参加元宵节的聚餐。这是一个吉祥的节日,春节之后的第15天,人们在每年的这一天庆祝神明把光亮带回这个世界。但是杨和薛的身上没有散发出任何光亮。他们都没有想过要开始一段感情,即使这个聚会也没有改变他们的想法。薛说:“我的朋友说,他是一个诚实、肯干的人,但是我根本不想考虑这件事。”30多岁的杨认为24岁的薛“只是个孩子”。

薛和杨住在同一个阴暗的安置所中。2009年1月,杨从她姑姑家里回来之后的一个月,他收到了政府的补偿金——8800美元补偿他儿子的死亡,1460美元补偿他妻子的死亡。他用这些钱买了一个二手的SUV,这是似乎是一笔丑恶的交易:他的妻子和7岁儿子的生命只换来一辆三菱帕杰罗。他想用这辆车从事北川和他的家乡片口之间的山区运输业务。然而,在业务真正开始之前,他需要鼓起勇气来克服独自驾驶的恐惧,不仅仅因为危险、崎岖的山路,还因为那可怕的一天留给他的回忆。

杨和薛的第二次见面,是由他们共同的朋友安排的一次公园野餐,这次双方依然没有擦出浪漫的火花。但是谈话还是令人愉快的。30来岁的杨司机温柔、善于言辞,与薛的未婚夫有些相像。尽管薛比杨的妻子小了10岁,但她也是一个成熟、易于相处的人。他们还是有些不情愿。他们之间的关系算是一种对死者的不敬吗?他们的内心都受到了巨大的伤害而无法开始任何的新生活吗?

几个星期之后,杨邀请薛到家里吃饭,他开着自己的三菱出现在她面前,车里还有他的姐姐和大舅子。这算是一个家庭决定了。杨说:“我承受着巨大的再婚压力,这是我考虑这个问题的唯一原因。”从那一天开始,两个幸存者开始在安置点中一起过夜,他们互相安慰,度过一天里最黑暗的时刻。他们很少提及自己脑海中时常闪现出的恐怖场景,他们都经历过类似的体验,这已经足够了。杨说:“她也受了很多苦,所以我相信他能理解我。”

他们的婚礼定在夏天举行,但是杨还有一个心愿尚未了结。距婚礼还有几个星期的时候,在他一个懂电脑的表弟的帮助下,杨为他的妻子和儿子建立了一个网站。网站的内容很简单,只有一些生活照和简要的描述。这些描述不大像墓志铭,更像是一些刊物年鉴的措辞。对妻子,他写道:“罗雪梅,女,1973年5月8日生……处事认真,打理家庭!”对儿子,他写道:“张瑞明,男,2000年9月20日生……聪明、可爱、活泼!”

杨还有一些旧物,装在几个盒子中。但是他把前妻的照片放在他父母的家里,那里距北川有5个小时车程。他儿子的旧物被寄存在他朋友的家中。他说:“我不能忍受看到他们的心情。”

他们的婚礼在当地的宾馆持续了一整天,有100多人参加。其中大部分是薛的朋友,这些来自北川的地震幸存者还住在临时安置点中,他们渴望用鱼、虾、鸡肉这些盛宴来替换早已吃腻的速食面。当天的大雨让杨的很多亲戚和朋友无法从山区中的片口赶来,但是为他家人预留的一个餐桌旁,坐着4个来自政府宣传部的新朋友。他们一直努力促成杨的再婚。现在,他们摘下眼睛,为新人敬酒,并鼓励他们开始新生活。

一年前的4月份,地震灾区上出现了一个奇怪的场景。20对夫妇穿着颜色艳丽的民族服装,在改造得具有迪斯尼风格的村庄街道上唱情歌,一整队电视摄像机关注着他们的舞蹈动作。这有点像一部中国的肥皂剧拍摄现场,但实际上是政府精心安排的一场震后鳏寡人士的集体婚礼。就像当地党委书记陈省春所说:“这是美丽的新北川的缩影。”

这些新人手挽手地走过石桥、城堡和瞭望塔,这些都是仿造羌族少数民族的古代村落重新修建的。新人中没有一对是住在这里的,重建的石头村庄Jina被设计为一个旅游景点。但这并不妨碍这些新人——其中有些人是在几个星期前才第一次见面——随着摄像机的镜头举行了传统的羌族婚礼仪式:随着古老的音乐起舞;种下象征幸福的树苗;在仪式结束后向人群抛洒玉米粒和粟子以祈求好运气。

这场集体婚礼被制作成一期感人肺腑的电视节目,在地震一周年的三个星期前播出,它同时是一个信号,表示幸存者们已经把悲剧抛在身后,继续前进。就像陈所说:“勇敢地追求一个幸福、崭新的开始。”更重要的是,这个活动展示了政府全方位重建四川的努力,从城镇施工和开发新的旅游产业,到“重建家庭”。为了成功举办这次集体婚礼,当地官员们扮演了媒人和心理教练的角色。北川县长经大忠对媒体说:“让这么多人下决心再次结婚不是件容易的事,所以我们帮助他们中的一部分找到对象,还提供了心理咨询服务,以打消他们的顾虑。”

设施重建的规模是令人震惊的。北川周边的每一条道路、桥梁、学校和工厂都被重新建好。北川以南15英里处的一片平地在不到一年的时间里已经变成了一个新城市——永昌。在一大片密集的多层建筑上,70多架巨型起重机像一群巨大的昆虫来回盘旋。随着北川新的县政府平地而起,山区中的鬼城变成了一个“地震博物馆”。中国游客已经成群结队地前往那里,在高处用望远镜盲目地凝视这片废墟(5分钟80美分),或者购买一些恐怖的合成照片——大部分来自家庭成员被废墟掩埋的小贩。

利用人们这种窥阴癖的本能来赚钱,仅仅是北川变成“一个国际知名的旅游中心”计划之一,另一项计划是让羌族少数民族成为旅游卖点。北川居民中的60%都是所谓的“云中人”的后代,他们的文化可以追溯到3000年之前。羌族的习俗和语言几乎已经消失,这是拜现代化进程和强制推行的同化政策所赐。但是现在,当地政府在Jina重新复活了一个羌族文化版本,就是举办那场集体婚礼的村庄,并把那里作为样本。这个石头村庄在地震中被夷为平地,但仅过了7个月,它就被重新建成一个羌族风格的主题公园。住在那里的69个家庭都穿上节日的羌族服装,随着羌族音乐起舞,用传统的饰物装点每一所房子:玉米穗、辣椒、山羊头骨……还有中国国旗。

国旗的出现并非偶然现象。政府通过在中国的五星红旗下主办“地震婚礼”,成功地把继续生活和再次结婚转化成一种爱国的责任。再婚不但能给个人带来好处,还可以让国家显著受益。在贫困的四川农村地区,有两个成年人的家庭要比单亲家庭更容易在没有政府帮助下生存下来,政府的重建负担也可以合二为一。

政府对社会稳步前进的全情关注,也是一种帮助人们忘却的方式。地震中,数千所质量低劣的学校倒塌,5300多名学生因此而丧生。为淡化公众对此的批判,政府给予地震中失去孩子的父母一笔补偿,但条件是他们要从此闭嘴,同时还要签署一份保证书,“保证遵守法律并维持社会稳定”——一种暗示的警告不要再提出这个问题。2月份,谭作人,一位详尽列举遇难学生名单的社会活动家,被判处5年监禁,罪名是一些不相干的指控,其中很多被怀疑是含有政治动机。再婚的双方被认为会把心思花在展望家庭的未来,而不是继续提出过去那些令人不快的问题。

Jina的婚礼仪式结束之后,一个政府车队把这20对新人送到机场,北川政府出资送他们到中国南部的海南岛沙滩去渡蜜月。行程虽然只有两天,但已经足够中国电视台拍摄最后几个镜头了。新人们一开始都抱有试探的心态,但很快他们就手挽手地冲上海滩,对着镜头描述他们未来的梦想。用电视拍摄术语来说,这是一个完美的最后镜头。

天刚蒙蒙亮的时候杨春就已经起床了,他用水洗了把脸。他的新妻子薛颖在床上多逗留了一会,床上罩着粉红色的帐子,上面有一个囍字装饰的婚结。杨出门把三菱打火预热,他把薛绣好的熊猫图案鞋垫塞进鞋子里。薛无力地刷了刷牙,抓起一本绿色的小册子,这是他们前往四川第二大城市绵阳的路途中需要的东西。

杨在六车道的高速公路上开得极为谨慎,一直没超过每小时40英里的速度。薛说:“我在车里的时候他总是很小心。”这种速度对一个曾经每天在通往片口的山区道路上颠簸的司机来说很不寻常。杨原先总是加速赶路,试图在每月700美元的收入水平上多挣一些。按当地标准,这已经是一个很体面的收入了。

杨的谨慎有另外一个原因——他的妻子怀孕了。车里同时搭载着他们这个新家庭的未来、希望和幸福的源泉,以及中国传统观念所认为的养老的保证。这个孩子还代表了这对夫妻即将超越2008年5月12日的恐怖,只有新生活才能填补心灵的空虚。

作为震后政策的一部分,中国政府颁布了一项不寻常的法令,免除了计划生育政策对大约8000个失去独子的家庭的约束。一项新的“再生育服务”为这些家庭提供了免费的咨询、孕期就诊服务,还提供恢复输精管切除和输卵管结扎手术。在最初了7个月里,北川有802个家庭获得官方批准,可以再生一个孩子。截止到去年年底,即震后的18个月,中国计划生育委员会报告,接受以上服务的女性共生育了1662个婴儿,还有1100多人已经怀孕。今年,这个数字还会继续升高。

不是所有人都这么幸运。回到片口,杨的老朋友陆世华还在生活的道路上挣扎前进。陆的第一任妻子在16年前分娩时去世,他唯一的女儿在北川中学倒塌中遇难。陆在震后很快结婚,现年41岁的他很想再要一个孩子。在当地的一个餐厅里,他要了啤酒和白酒,但又不想喝了。他靠过来轻声说:“饮酒会伤害我的生育能力。”一年多的时间里,陆和他的新妻子一直在尝试怀孕。陆和我说:“医生说生理上没有问题,所以多半是压力的作用。”尽管他心怀沮丧,但是他谈到杨的时候并没有表现出妒忌。陆说:“杨组建了新家庭,他再次看到了希望。”几个月之后,陆的妻子也一定会怀孕的。

杨和薛来到绵阳的计划生育诊所,他们出示了那本绿色的小册子,这将确保他们作为地震幸存者可以得到免费的就诊服务。薛走进了妇产科检查室。杨把他妻子的钱包夹在胳膊下面,走到外边。他的头上是一幅海报,内容是描述工人在正式场合里正确的鼓掌方式。不久,一个戴白手套的医生招呼他进屋。几分钟之后,杨和薛一起走出来,两个人的脸上都洋溢着微笑。薛手中紧紧攥着超声波照片,那个模糊的小白点证实了生命的存在,而且状况良好。杨说:“一切正常,很高兴知道一切都会变好。”

原文:

From left, Yang Chun and Xue Ying, who is holding their son, Zhang Ruijun; A memorial marker, overlooking Beichuan, reads “In deep mourning for compatriots lost to the 5.12 earthquake.”

THE NEWLYWEDS are perfectly happy, can’t you see?

REBUILDING LIVES Liu Yinhu says he spent a month persuading a grief-stricken Zhao Yonglan to marry him.

In the poster-size wedding photographs that cover the walls of their home in rural Sichuan Province, the couple frolic in a field of green clover. They nuzzle against a backdrop of autumn leaves. They cuddle on a beach under an azure sky. In each soft-focus image, the bride — a 25-year-old former clothing vendor named Xue Ying — appears in a strapless white gown and a glittering tiara. The groom — Yang Chun, a 37-year-old shuttle-bus driver — wears a white tux and a bow tie; his crooked, nicotine-stained teeth appear straight and white.

The image set against the fall foliage is captioned “Romandic Story,” in garbled English. On the tropical beach, Xue leans back into Yang’s arms, her veil blowing in a breeze; a smile sparkles on Yang’s face. The caption, again in English, a language neither understands: “I Make a Wish With U.”

Yang and Xue invited me into their home one afternoon last fall. They married in July and were pleased to show off the trappings of connubial bliss. The dreamscapes were an artifice, a confection of false memories manufactured by a local photo studio. Digital enhancement brightened their smiles, erased their blemishes and slathered their marriage in a gooey layer of romanticism. It hardly seemed to matter that Yang and Xue lived in the mountains of landlocked Sichuan Province in southwestern China and had never been to a beach. The photos served a more fundamental purpose: to paper over a past too painful to bear.

For the past two years, Yang and Xue have been striving, in their own separate ways, to escape the shadow of May 12, 2008. On that day, at 2:28 p.m., a 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck Sichuan. In barely 80 seconds, their worlds were obliterated. Yang’s wife, a shopkeeper, was one of more than 15,000 people entombed in the rubble of their hometown, Beichuan. Their only child, a 7-year-old boy, was crushed when the Qushan Primary School, like thousands of other school buildings across the region, collapsed like an accordion. A few hundred yards away, Xue scrambled out of her home seconds before it crumbled only to discover that her fiancé had been buried by a landslide.

So staggering was the scale of destruction unleashed by the Sichuan earthquake that, much like the Haitian quake in January, its horror was often reduced to a series of statistics: more than 87,000 dead or missing, nearly 400,000 injured, upward of five million homeless. Beichuan, nestled along a river bend deep in the mountainous folds of Sichuan, stood nearly 60 miles north of the quake’s epicenter. It was a beautiful spot, but its underlying geology — the convergence of two fault lines — was so volatile that officials had for years considered razing the town, which was the county seat, and rebuilding it elsewhere. The quake did the job in an instant, leveling 80 percent of the town’s buildings and killing an estimated two-thirds of its 22,000 inhabitants, many of them members of the Qiang ethnic minority.

Two years later, Beichuan is a ghost town encircled by razor wire and Chinese soldiers. Most survivors still live in temporary housing, the blue-roofed aluminum cities that dot the earthquake zone. Some, like Yang and Xue, moved to Anchang, which is serving as the county seat until construction is completed on a new one, which will be known as Yongchang, or Eternal Prosperity. This replacement city, rising on the flood plain 15 miles south of Beichuan, is a small part of the $440 billion that China has reportedly spent on relief and reconstruction. Sichuan, whose armies of poor migrant workers helped fuel the economic boom in eastern China, is now receiving government largess, from housing, roads and infrastructure to the creation of a new industry: “earthquake tourism.”

Looming over the physical reconstruction, however, has been another question: How can society rebuild? In China, one answer has been to pair grieving men and women to create instant families that will help ensure social and economic stability. For Westerners, marriage choices tend to be based on individual notions of love or romance, or at least that is how we see it. But in Sichuan, marriage is, first and foremost, about family and community. Families shattered by the earthquake are not just personal tragedies; they are a fissure in the foundation of society.

Coaxing earthquake survivors into remarriage has become a community obligation. Unlikely volunteers have joined in the matchmaking efforts, from former in-laws to the leaders of the local Communist “work units” to which every family in this part of rural Sichuan is still assigned. Behind them is the Chinese government. The state, which has long seen fit to intervene in the most private aspects of people’s lives, including reproductive rights, has avidly promoted — and in some cases even arranged — what it dryly calls “restructured families.”

Deng Qunhua, a former seamstress, started her matchmaking service after losing her home and business in the earthquake.

By the end of 2008, less than eight months after the earthquake, 614 survivors from Beichuan alone had already remarried, according to Wang Hongfa, a local civil-affairs official. (The number across Sichuan’s earthquake zone, though not made public, is estimated to be well into the thousands.) That so many earthquake survivors have already remarried is not surprising in itself; but in many cases, these are widows marrying widowers, two survivors striving to get back onto solid ground.

Yang and Xue are feeling their way forward. One evening when I visited their house, smoke billowed out of the kitchen, filling the room with an acrid blast of chili paste. Yang, in a blue chef’s apron, stuck his head out of the kitchen. Tears streamed from his hangdog eyes, but he had a grin on his face. “Huiguo rou!” he said — he was making the “twice-cooked pork” that is a Sichuanese specialty. Xue smiled up from her chair, holding a box of insoles she had embroidered to make Yang’s shoes more durable and comfortable on his long days driving. Her mother and brother were visiting, and Yang relished the chance to cook for a family again. A few minutes later, he emerged from the kitchen with a parade of dishes: chicken feet, cold sesame noodles, beef and potato stew and twice-cooked pork, all to be washed down with rice liquor. Yang called his new family to the table and, with a flash of yellow teeth, declared, “Let’s eat!”

Hey, you just sneaked off, where are you now?”

The last text message from Luo Xuemei, Yang’s first wife, sent hours before the earthquake, stared back at him from his cellphone. Yang left their home in Beichuan early that morning not wanting to disturb his sleeping wife and son. He was headed for Piankou, his home village, to buy mushrooms and honey for his trading business.

Now, four days after the quake, the text message was all he had left. It had taken him two days to hike the 40 miles across mountains gashed by landslides to get back to Beichuan. He searched hospitals, stadiums and refugee camps, hoping to find his wife and son alive. He lifted the covers off dozens of swollen corpses pulled out of his son’s collapsed school. “It was too much to take,” Yang told me. He threw himself down on the rubble and wailed, “God, you are too cruel!”

More than a thousand people were crawling across the wreckage the day Yang arrived, all sobbing and shouting out the names of loved ones. Xue was there, too. An acquaintance of Yang’s wife — she sold clothing downtown, too, after a stint in a tile factory — Xue was looking for her 35-year-old fiancé in the rubble. Now she wondered if the dead weren’t better off than the living. It was her fourth day wandering through the wasteland, clawing at the debris with bare hands. Her parents and brother were nowhere to be found (they turned up alive on the fifth day), and she knew, deep down, that her fiancé could not have survived the landslide that buried his home under a hundred feet of earth and cement. Xue stopped digging. Her lover was dead, and so, too, were their dreams of starting a family together.

Beichuan was declared a mass grave, leaving thousands of unrecovered bodies under the ruins. For the next few months, Xue lived alone in a government-issue tent outside a local stadium, eating crackers and instant noodles, unable to sleep without seeing images of corpses appearing with her fiancé’s face. Yang returned to his parents’ home in Piankou and retreated into a suicidal stupor. He lost more than 30 pounds. He slept very little. As soon as he closed his eyes, he would see his wife and son staggering among the ruins, waiting for him to come save them. Yang spoke to nobody about the tragedy. “I couldn’t dump all this on my parents or in-laws,” he said. “They had suffered great losses, too. So I kept it all inside, wondering why life should be lived anymore.”

The only way to pull Yang back from the brink, his family decided, was for him to remarry as quickly as possible. “My parents, my older sister, my younger sister: they all pressured me to move on,” Yang recalled. “My wife’s older brother recruited my friends to look for a new wife for me. Even my mother-in-law, one month after the earthquake, urged me to get married again.” Yang also got a call from the Communist Party’s local propaganda department. The deputy director of the department, a 33-year-old man named Feng Xiang, lost his young son in the same Qushan Primary School collapse in which Yang’s son died, and subsequently committed suicide. Feng’s colleagues encouraged Yang to start a new life — and offered to do anything they could to help.

The notion of remarrying, however, seemed obscene to Yang, he said; it would be a betrayal of his wife and son. Yang didn’t want to reconnect with people; he wanted to run away. So when a favorite aunt in faraway Hebei Province sent for him, Yang left Sichuan behind. Gradually, with a combination of home cooking and herbal medicine, his aunt gave him back a life.

TWO BULGING LEDGERS sit on the matchmaker’s wooden table — one for men, the other for women. Inside the books, row after row of names are recorded in the precise handwriting of Deng Qunhua, a 42-year-old former seamstress who started her matchmaking service after losing her home and business in the earthquake. Each name on Deng’s list is followed by the client’s age (ranging from 22 to 78), along with height, education, employment and desired traits in a partner. But there is another more pertinent detail — a strangely formal two-character phrase — that appears next to a disproportionate number of names: , sang’ou, meaning “bereaved of one’s spouse.” “These are the earthquake widows and widowers,” Deng says, tracing a finger across the page. “Most of them don’t ask for much — just a chance to get back part of what they have lost.”

Tapping into this new market of lonely hearts came naturally to Deng. Suddenly single again herself, after divorcing her husband in the post-quake trauma, the gregarious Beichuan native began commiserating with the lovelorn — and collecting names. Women join her list free, while men pay 200 yuan (about $30) for an unlimited number of introductions until they find a suitable match. Deng runs her business off a tabletop in Anchang, 10 miles south of Beichuan. But there are other matchmakers in town; even the local government has a service. So Deng travels into the mountains, plastering photocopied lists on the rocks, poles and village walls along the way.

So far Deng has brokered more than a hundred matches involving earthquake widows and widowers. Those are the cases, she says, that make her feel less like a businesswoman and more like a social worker. “The earthquake survivors often feel that it may be too soon to look for a new spouse,” Deng says. “But when they see other people with a warm family home, they want that for themselves.”

Finding such a refuge, however, is no simple task. Grief and trauma still consume many earthquake survivors. New companions must also deal with the remnants of their partners’ former lives: debts, disputed property, in-laws and parents and, perhaps most important, children. On Deng’s list, the most desired trait in a partner, repeated on almost every entry, is not money, looks, character or education; it is simply “no burdens.” Those saddled with the heaviest burdens — especially middle-aged women with children — move slowly off the list, while the young and the elderly tend to have more luck. Even so, some of these hastily arranged “earthquake marriages” have already fallen apart. Deng recalls one that ended in divorce after just 12 days — “a record,” she says.

Early last year, a local doctor came to add his name to Deng’s list. The man escaped death by chance; he was away from work when his hospital crumbled. His wife was not so lucky. Rescue workers found her body clutching a baby, not her own, whom she evidently tried to save. Deng began taking down the doctor’s details: “57 years old, bereaved of spouse, handsome. . . .”

A couple of weeks later, Deng found herself accompanying her new client to the disaster site where his wife died. She comforted him as he wept and lighted incense in her memory. The doctor and the matchmaker started seeing each other, their romance followed quickly by talk of marriage. Deng knew her fiancé was still in mourning, deeply wounded by the tragedy, but still it took her by surprise when he broke off the engagement. At 42, she is 15 years his junior. But he considered her to be too old. Though he has an adult son, he wants to start another family. So Deng has no choice but to fulfill her professional duty — the doctor, after all, has already paid the $30 fee. The photocopied lists she now pastes on village walls carry the doctor’s data, along with his final requirement: “a woman under 30 who can bear children.”

Children are not an issue for the older couple trying to make a new start in Room 22 of a temporary settlement just south of Beichuan. Liu Yinhu, a 56-year-old day laborer, dug in the rubble of a mountain construction site for two days to find his wife’s body. Zhao Yonglan, a round-faced peasant, lost nearly everything in the quake: her husband, two grown children, a sister and a brother-in-law and her home. Liu and Zhao, who is 54, knew each other as small children. But when Liu’s older sister reintroduced them a few months after the quake, Zhao was lost in grief. “I called her every day for a month to convince her,” Liu says. “I kept telling her, ‘It’s good to have another person take care of you. You’re too young to lose hope.’ ”

Zhao eventually relented, and in January 2009, they held their wedding celebration at a local restaurant in the settlement, inviting enough family and friends to fill eight tables. I joined the couple and Zhao’s 84-year-old mother for a meal at the same restaurant almost a year later. Over plates of wild mushrooms and cumin-flavored pork ribs, Liu told stories of their courtship, while Zhao blushed and poked him playfully. Then Zhao’s mother let it slip that the newlyweds are, in fact, first cousins. “We know it’s not right,” Liu said. “But we’re too old to have children, so what does it matter?”

Last year, during the traditional festival when Chinese mourn the dead, Zhao joined the throngs heading into Beichuan, where her family’s remains still lie under the rubble. Near the razor wire at the edge of town, she crumpled to the ground, unable to go farther. “I was too scared,” she said, pulling on her ear to keep from crying. Liu put a hand on her shoulder and gave her a tissue to dab her eyes. Zhao said that she would try to muster the strength to go back. “I couldn’t go alone,” she said, looking at Liu. “But with his help, this time I will make it.”

YANG AND XUE, the shuttle driver and the former clothing vendor, first met in early 2009, when a mutual friend persuaded them to join a group lunch during the Chinese lantern festival. It was an auspicious occasion, the 15th day of the new lunar calendar, a celebration of the spirits who bring light back into the world each year. But there was no glimmer for Yang and Xue. Neither wanted to start a new relationship, and the meeting didn’t change their minds. “My friend said he was an honest, down-to-earth man,” Xue says. “But I didn’t want to consider it at all.” Yang, who is in his mid-30s, dismissed the 24-year-old Xue as “just a kid.”

Both Xue and Yang lived alone in the same dismal refugee camp. In January 2009, a month after returning to the province from his aunt’s house, Yang received $8,800 in government compensation for his son’s death — and another $1,460 for his wife. When he spent the cash on a secondhand S.U.V., the trade seemed ghastly: his wife and 7-year-old boy for a Mitsubishi Pajero. He bought the car to start a new business shuttling people across the mountains to his home village, Piankou. It would take time, however, before he mustered the courage to make the drive himself. The mountain switchbacks were treacherous — and filled with the memories of that horrible day.

When Yang and Xue met a second time — at a picnic in the park arranged by their mutual friend — there still were no romantic sparks. But the conversation was pleasant enough. Like Xue’s fiancé, Yang was a gentle, soft-spoken driver in his mid-30s. And though Xue was a decade younger than Yang’s wife, she, too, was easygoing and mature. Still, they were reluctant. Would a new relationship dishonor the dead? Were they both too broken to build anything new?

A couple of weeks later, Yang invited Xue to lunch and showed up in the Mitsubishi with his sister and brother-in-law in tow. This was to be a family decision. “For me, the pressure to get remarried was huge,” Yang says. “That’s the only reason I considered it.” From that day on, the two survivors spent their nights together in the shelter, comforting each other through the darkest hours. They rarely talked about the hideous images that occasionally flooded their minds. It was enough that they had both gone through a similar experience. “She suffered a lot, too,” Yang says, “so I think she understands me.”

The wedding was set for summer. But Yang still had one loose end to tie up. A few weeks before the marriage, with the help of a computer-savvy cousin, he created Web sites for his wife and son. The sites were simple, each with a snapshot and a brief description that reads less like an epitaph than a yearbook entry. For his wife, he wrote: “Luo Xuemei, female, born May 8, 1973. . . . able to do things very seriously and take charge of the family!” For his son: “Zhang Ruiming, male, born Sept. 20, 2000. . . . smart, lovely, and lively!”

Yang still has boxes of family mementos, but he keeps the photos of his first wife at his parents’ house in Piankou, five hours across the mountains. His son’s are stored at a friend’s apartment an hour away. “I can’t bear to look at them,” he says.

More than a hundred guests showed up for the all-day wedding celebration at a local hotel. They were mostly Xue’s friends, fellow earthquake survivors from Beichuan who were still living in temporary shelters, eager to trade their instant noodles for a feast of fish, shrimp and chicken. Heavy rains prevented many of Yang’s friends and family from coming across the mountains from Piankou. But at his family’s table there sat four new friends from the government propaganda department. They had pushed Yang to remarry all along. Now, lifting their glasses, they toasted the newlyweds — and urged them to start building a family.

A YEAR AGO IN April, an odd spectacle unfolded in the earthquake zone. Twenty couples in brightly colored ethnic costumes sang love ballads on the streets of a Disneyfied village, their choreographed moves followed by a phalanx of television cameras. The event resembled the production of a Chinese soap opera, but it was actually a government-sponsored mass wedding of earthquake widows and widowers, orchestrated to show, as the master of ceremonies — a local Communist Party chief named Chen Xingchun — put it, “the epitome of a beautiful new Beichuan.”

Walking arm in arm, the newlyweds promenaded past stone bridges, fortresses and watchtowers, all rebuilt to look like an ancient village of the Qiang ethnic minority. None of the men and women lived there; the reconstructed stone village, Jina, is designed to be a tourist site. But as the cameras rolled, the couples — some of whom met for the first time just a few weeks before — performed ancient Qiang wedding rituals: dancing to traditional music, planting saplings to symbolize happiness and, as the celebration ended, throwing corn and millet over the crowd for good fortune.

The group wedding made for heartwarming television. Staged less than three weeks before the quake’s first anniversary, it also served as a signal for survivors to leave the tragedy behind and move on, as Chen said, “in courageous pursuit of a happy, new start.” Just as crucially, the event showcased the government’s efforts to rebuild Sichuan at every level, from the reconstruction of towns and the creation of a new tourism industry to “the restructuring of families.” To pull off the mass wedding, local officials acted as matchmakers and motivational coaches. “It’s not easy for many of these people to decide to marry again,” Jing Dazhong, the Beichuan mayor, told reporters. “So we helped some of them find the right person and provided psychological consultation to ease their uncertainties.”

The scale of the physical reconstruction effort is staggering. Nearly every road, bridge, school and factory in the areas surrounding Beichuan has been rebuilt. An empty field 15 miles south has been transformed, in less than a year, into the new city, Eternal Prosperity, a vast grid of multistory buildings over which more than 70 building cranes hover like a swarm of gigantic insects. As Beichuan’s new county seat rises on the plains, the ghost town in the mountains is set to be turned into an “earthquake museum.” Chinese tourists already flock to the viewpoints above the town to gawk at the wreckage through binoculars (80 cents for five minutes) and buy gruesome photomontages — often from vendors with family members buried in the rubble.

Capitalizing on this voyeuristic impulse is one part of Beichuan’s plan to become “an internationally renowned travel destination.” The other is to turn the Qiang ethnic minority into a tourist draw. Nearly 60 percent of Beichuan’s residents descended from the so-called “people of the clouds,” whose culture dates back 3,000 years. Qiang customs and language have nearly vanished, victims of modernization and a forced policy of assimilation. But now the local authorities are reviving a version of Qiang culture, with Jina — the site of the mass remarriage ceremony — as its showpiece. Leveled by the earthquake, the stone village was entirely rebuilt in just seven months to become a Qiang-style theme park. The 69 families who live there wear festive Qiang costumes, dance to Qiang music and decorate every house with traditional emblems: corncobs, peppers, sheep skulls . . . and Chinese flags.

The flags are not incidental. By holding its “earthquake wedding” under China’s five-star banner, the government turned the act of moving on and remarrying into a patriotic duty. Remarriage can bring tangible benefits not just to the individuals but also to the state. In impoverished rural Sichuan, a family with two adults has a better chance at surviving without government aid than a single parent. The burden on reconstruction is also reduced from two homes to one.

The government’s emphasis on forging ahead is also a way of forgetting. To blunt criticism over the collapse of thousands of poorly built schools, which killed more than 5,300 students, the government silenced parents who lost their children, giving them compensation only after they signed a pledge “to obey the law and maintain social order” — an implicit warning against ever raising the issue again. In February, Tan Zuoren, an activist who was compiling an exhaustive list of the dead students, was sentenced to five years in prison on unrelated charges that many suspect were politically motivated. Remarried couples, it is presumed, will have their eyes too fixed on the future to raise uncomfortable questions about the past.

When the wedding ceremony in Jina ended, an official caravan whisked the 20 couples to the airport. The Beichuan government was sending them on an all-expense-paid honeymoon to a beach resort on Hainan Island in southern China. It was only a two-day trip, but that was enough time for Chinese television crews to frame the final shot. The newlyweds seemed tentative at first. But soon they were strolling down the beach, hand in hand, sharing on camera their dreams about the future. It was, in television terms, a perfect wrap.

The morning sky was barely streaked with light, but Yang Chun was already up, splashing water across his face. His new wife, Xue Ying, lingered a while longer in bed under a canopy of pink gauze and a red wedding knot emblazoned with the symbol for “double happiness.” Heading out to warm up the Mitsubishi, Yang slipped a pair of Xue’s embroidered insoles — these with a panda motif — into his shoes. Xue groggily brushed her teeth and grabbed the green booklet they would need for the trip to Mianyang, Sichuan’s second-largest city.

On the six-lane highway, Yang drove cautiously, never exceeding 40 miles per hour. “He’s always very careful when I’m in the car,” Xue said. The slow pace was unusual for a shuttle driver who careers over the bone-jangling mountain passes to Piankou every day, trying to hasten his trips and increase his $700 monthly income, a decent one by local standards.

There was another reason for Yang’s caution: his wife was pregnant. Riding along in the car with them was the future of their new family, a source of hope and potential happiness — and, as tradition dictates in rural China, insurance in their old age. The baby also represented the couple’s best chance for moving beyond the horror of May 12, 2008. Only a new life could begin to fill the void.

In the aftermath of the quake, the Chinese government issued an unusual collective exemption to its one-child policy for the estimated 8,000 families who lost their only children. A new “re-reproduction service” offered these families free consultations, fertility treatment and surgery to reverse vasectomies and tubal ligations. In Beichuan, 802 families registered for official permission to have another child in the first seven months. By the end of last year, some 18 months after the quake, China’s family-planning commission reported that 1,662 babies were born to women eligible for these services — and more than 1,100 women were pregnant. This year, the numbers are expected to be even higher.

Not everybody has been so fortunate. Back in Piankou, Yang’s old friend Lu Shihua struggled to move forward. Lu’s first wife died in childbirth 16 years ago; his only daughter died in the collapse of the Beichuan Middle School. Lu remarried soon after the earthquake, and at 41 he was gripped by the need to have another child. At a local restaurant, he ordered beers and baijiu, the traditional rice liquor, but then declined to drink. Leaning over, he whispered, “Drinking is supposed to hurt my potency.” For more than a year, Lu and his new wife had been trying to conceive. “The doctor says there’s no physical problem,” Lu told me at the time, “so it’s probably just stress.” Despite his frustration, Lu showed no trace of envy when he talked about Yang. “Now that Yang is forming a new family,” Lu said, “he sees that there’s hope again.” Months later, Lu’s wife would get pregnant, too.

When Yang and Xue reached the family-planning clinic in Mianyang, they presented the green booklet — which guarantees free service to quake survivors — and Xue disappeared into the obstetrician’s checkup room. Tucking his wife’s purse under his arm, Yang paced the hallway outside, underneath a poster that showed the proper way for workers to applaud at official functions. It wasn’t long before a white-gloved doctor waved him into the room. Minutes later, Yang and Xue emerged together, smiles spreading across their faces. In her hand, Xue clutched the image from the ultrasound, its smudgy white blur confirming the reality — and the good health — of their child. “Everything is O.K.,” Yang said. “It’s good to know everything is going to be O.K.” |