【中文标题】为什么中国母亲是优秀的-《猛虎母亲的战斗颂歌》节选(中西方教育理念比对系列文章之一)

【原文标题】Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior

【登载媒体】华尔街日报

【原文作者】AMY CHUA

【原文链接】http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704111504576059713528698754.html

没有聚会、没有电视、没有电脑游戏,只有持续数小时练习演奏乐器的生活可以造就愉快的童年吗?孩子们如果反抗怎么办?

Amy Chua和她的女儿们——Louisa和Sophia——在康涅狄格纽黑文的家中。

很多人在奇怪中国的父母是如何培养出从传统角度看如此成功的孩子。他们不明白,这些父母是怎样培养出那么多数学奇才和音乐天才?这些家庭内部是什么样的?他们是否也可以这样培养孩子?我可以回答你们这些问题,因为我就是这样做的。以下是我的两个女儿Louisa和Sophia绝不允许做的事情:

-参加在外过夜的活动

-参加聚会

-参加学校剧演出

-抱怨不能参加学校剧演出

-看电视或者玩电脑游戏

-选择自己喜欢的课外活动

-任何一门课程得到A以下的分数

-除了体操和戏剧之外的任何一门课程不是第一名

-演奏钢琴或小提琴之外的任何乐器

-不练习钢琴或小提琴

我所说到的“中国母亲”是一个宽泛的概念,我认识一些韩国、印度、牙买加、爱尔兰和加纳的母亲都具有这样的品质。相反,我也认识一些具有中国传统品质的母亲,大部分都在西方出生,他们其实并不是中国人(自愿或者被迫)。“西方父母”也是一个宽泛的概念,西方的父母也不尽相同。

尽管如此,当一些西方父母认为他们过于严厉的时候,他们大都不了解中国母亲的做法。例如,我的西方朋友认为自己要求太严格了,因为他们让自己的孩子每天练习30分钟乐器,顶多一个小时。对中国母亲来说,第一个小时仅仅是热身,第二个和第三个小时才叫难熬。

尽管我们厌恶文化成见,但是现实中有成堆的研究结果表明,中国父母和西方父母在教育后代方面存在着显著的、可以衡量的差别。在一项针对50名美国母亲和48名中国移民母亲的调查中,大约70%的西方母亲赞同“在压力下取得的学业成绩对孩子不好”,或者“父母需要帮助孩子形成学习是乐趣的概念”的观点。与此相比,几乎没有一个中国母亲有相同的看法。大部分中国母亲说他们认为孩子应当是“最好的”学生;“学业成就代表教育的成功”;如果孩子在学校中不出色,就说明存在“问题”,家长就“没有尽到责任”。其它一些研究表明,中国家长与孩子每天花费在钻研学术问题方面的时间是西方家庭的10倍。而西方的孩子更喜欢参加体育运动。

中国父母明白一个道理,在你擅长做某件事情之前是不会有乐趣的。想做好任何事情你都必须要下功夫,而孩子们自己是不愿意下功夫的,这就是为什么必须要强迫他们的意志。从父母的角度来说,这通常需要毅力,因为孩子们会反抗。事情在刚开始的时候是最艰难的,西方父母往往在这个时候会放弃。但是如果处理得体,中国人的做事方式会形成一个良性循环。坚持不断地重复、重复、重复是成功的关键,而死记硬背是被美国人所摒弃的做法。一旦孩子开始擅长做某件事——无论是数学、钢琴、运动还是芭蕾舞——他/她就会得到赞赏、钦佩和满足感。这会增加他们的自信,让曾经不愉快的经历变得愉快起来。同时,父母在让孩子们下更多功夫的时候也会变得容易一些。

中国父母可以摆脱一些被西方父母奉为金科玉律的束缚。在我小的时候,有一次——或许不止一次——我对我的母亲非常不尊敬,我的父亲用福建方言极为愤怒地说我是“废物”。这种做法的效果很好,我感到非常可怕,对自己做的事情极为羞愧。但是这并没有伤害到我的自尊心,我清楚地知道他们对我有很高的期望,我也并没有真的认为自己一钱不值,像一堆垃圾。

Chua女士的相册:刻薄的我和Lulu在酒店的房间里,乐谱放在电视机上。

我自己成年之后,也曾经对Sophia做过同样的事情,当她对我极为不尊敬的时候,我用英语叫她“废物”。当时的场合是一个家庭聚会,我立即被其它客人所排斥。一个名叫Marcy的客人非常愤怒,眼泪都流出来,她不得不早早退席。聚会的主人,我的朋友Susan想尽办法让我重新融入到剩下的客人中。

事实是,中国父母会做一些在西方人看来难以置信的事情,有些事情甚至可以到法院去起诉。中国母亲会对她的女儿说:“嘿,胖子,减减肥吧。”而西方父母不得不拐弯抹角地提及这个话题,比如讲讲“健康”啦,绝对不会说出“肥”这个字。然而结果却是他们的孩子们不得不接受饮食紊乱和负面自我形象的治疗。(我有一次看到,一个西方父亲向他的女儿祝酒,说她“美丽而且极有能力”。女儿后来和我说,这些话在她听起来都是废话。)

中国父母可以命令他们的孩子把事情搞定,西方父母只会让孩子尽力而为。中国父母会说:“你太懒了,班上的同学都比你做的好。”西方父母则沉浸在对成绩的矛盾态度中,总是试图让自己相信,他们对孩子的表现没有失望。

长期以来,我一直在努力思考为什么中国父母可以做某些事情而不用顾忌付出代价。我认为在双方的思维模式中,有三个重大的区别。

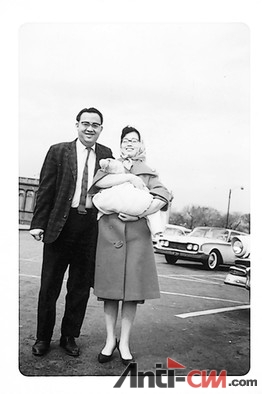

新出生的Amy Chua在她母亲的怀抱中,这是在她父母来到美国一年之后。

.首先,我发现西方父母极为关心孩子的自尊。当某件事情没有做好,他们担心的是孩子会怎么想,他们重复不断地让自己的孩子相信他们是多么的优秀,尽管他们在考试或者是一次表演中表现平平。换句话说,西方父母关心的是孩子的心灵。中国父母不是这样。他们表现的很强势、不脆弱,因此他们的行为方式截然不同。

举个例子。假如一个孩子在考试中得了一个A-,西方父母一般都会给予表扬。中国母亲则会面带惊恐地喘着粗气,问究竟是哪里出了问题。如果孩子拿着B的成绩单回家,一些西方父母还是会表扬孩子,另一些父母会让孩子坐下,表达他们进一步的期望。但是他们会非常小心,不让孩子感觉到自己没有能力、没有判断力。他们绝对不会说自己的孩子“愚蠢”、“没用”、“丢脸”。私下里,西方父母也会担心,是不是自己的孩子成绩太差了呢?会不会不具备学习这门课程的天赋?课程的设置,甚至学校是不是有问题?如果孩子的成绩没有提高,他们最终的做法就是去和校长见面,质问课程的教授方式,或者质疑教师的资历。

如果一个中国孩子得了一个B——现实中这是绝对不会发生的——首先会爆发出一声尖叫,是那种撕裂头皮的爆炸声。然后绝望的中国母亲会找来数十份,甚至上百份测试练习题,跟她的孩子一起做完,直到下次考试的成绩变成A。

中国父母对完美成绩的期望,是因为他们相信孩子是可以做到的。如果孩子没有做到,中国父母会假设原因在于孩子没有足够的努力。这就是为什么成绩不理想的解决方式总是责骂、惩罚和羞辱。中国父母相信他们的孩子是足够坚强的,可以承受这种羞辱,并以此作为进步的动力。(当中国孩子表现出色的时候,父母在家中也会毫不吝惜地给予表扬和鼓励。)

2007年Sophia在卡耐基音乐厅演奏。

第二,中国父母认为孩子欠他们一切。这种思维的起因不明,或许是儒家孝顺的理念与现实中父母为孩子做出了大量的牺牲所结合的产物。(中国母亲的确亲力亲为,花费了大量痛苦的时间亲自指导、训练、审问、监视自己的孩子。)总之,理念就是中国的孩子必须通过服从和让父母自豪的方式,用一生来偿还父母。

与此相比,我想大部分西方人不会认为孩子应当永远对父母怀有蒙恩之情。我的丈夫Jed实际上就有与此相反的观点,他曾经说:“孩子并未选择父母,他们甚至没有机会选择出生。是父母把生命强加给孩子,所以父母就有责任为其奉献。孩子不欠父母任何东西,他们的责任在于养育自己的孩子。”西方父母的这种理念让我震惊。

第三,中国父母认为他们知道哪些东西是对孩子最有好处的,因此会把自己的意志凌驾于孩子的自身愿望和偏好之上。这就是为什么中国的女孩在高中里不能有男朋友,为什么中国的孩子不能参加在外过夜的野营。中国的孩子甚至不敢对妈妈说:“我要在校园剧中演出一个角色,是农民6号。所以每天放学后我要在学校排练,从3点到7点。另外,周末你要送我去学校。”如果有哪个孩子敢这么说,上帝保佑他/她吧。

别理解错了,中国父母并非不关心自己的孩子。恰恰相反,他们愿意为孩子放弃任何事情。这只不过是不同的教育理念。

这里有一个与中国式强迫有关的真实故事。Lulu大约7岁的时候在学习演奏两种乐器,其中有一个钢琴曲《小白驴》,是法国作曲家Jacques Ibert的作品。这个曲子很欢快——你可以想象一下,一头小驴和它的主人在乡间的小路上缓步而行——但是对年轻的演奏者来说难度很大,因为两只手要同时奏出不同的旋律。

Lulu总是做不好,我们不停地练了整整一个星期,反复训练每只手的动作。但是一旦两只手同时演奏,其中一只手总是跟随另外一只手的节奏,曲子就进行不下去了。最后,上课的前一天,Lulu恼怒地宣布她不练了,生气地跺着脚。

“回到钢琴旁边,现在!”我命令她。

“你不能强迫我。”

“哦,我可以强迫你。”

回到钢琴旁边的Lulu让我付出了代价。她又踢又打,抓住乐谱撕得粉碎。我把乐谱拼起来,夹在一个塑料壳中,再也撕不坏。然后,我把她的玩具都搬到车上,告诉她如果明天还不能完美地演奏出《小白驴》,我就要把她的玩具一件一件地捐献给救世军组织。Lulu说:“你不是要去救世军捐献吗?怎么还不走?”我于是威胁她,没有午餐,没有晚餐,没有圣诞节和光明节礼物,没有生日聚会,未来两年、三年、四年都没有。她依然不能正确地弹奏出这个曲子,我说她是在故意让自己变得疯狂,因为她内心害怕自己真的无法成功地演奏。我让她不要偷懒、不要胆怯、不要自我放纵,更不要装可怜。

Jed把我拉到一边,让我不要再侮辱Lulu——我根本没有侮辱她,我是在激励她——他认为继续威胁Lulu不会有什么帮助。他还说,或许Lulu真的暂时无法掌握这种技巧——或许她还不具备这样的协调性——我有没有考虑过这种可能性?

“你根本不相信她。”我指责他。

Jed轻蔑地说:“真荒唐,我当然相信她了。”

“Sophia在她这么大时就可以演奏这首曲子。

“但是Lulu和Sophia不一样呀。”Jed说。

“哦不,不是这样,”我翻着白眼说。“每个人都有自己擅长的一面。”我嘲讽地模仿他的语气,“失败者当然也有自己擅长的一方面。你不要插手,我要把她搞定,不论花多长时间。我愿意做恶人,你踏踏实实地当受她们爱戴的好人,因为你给她们做烤饼,还带她们去看洋基队的比赛。”

我卷起袖子回到Lulu身边,我用尽了能想到的所有手段和技巧。我们一直在练习,没吃晚饭。我不让Lulu站起来,不许喝水,甚至不许去厕所。房间变成了战场,我甚至失控得尖叫。但是似乎效果是相反的,连我自己也开始怀疑这样的做法。

然而,出人意料的是,Lulu竟然演奏出了这首曲子。她的双手完全协调了,两只手沉着地演奏不同的旋律。事情就这样莫名其妙地发生了。

Lulu同时也发现自己竟然成功了。我摒住呼吸,她小心翼翼地试验了一遍,然后更加自信、流利地又演奏了一遍,旋律一点都没错。这时,她的脸上露出了笑容。

“妈妈,看——这不难!”然后她一遍接一遍地弹奏这个曲子,不愿意离开钢琴。哪天晚上,她和我睡在一起,我们互相拥抱着,开心地说着话。几个星期之后,她在一个表演会上演奏《小白驴》,其它父母都和我说:“真是一个精彩的演出——这个曲子充满了欢快和Lulu自己的感情。”

Jed后来也赞同了我的做法。西方父母总是在担心孩子的自尊受损,但是作为父母,最不应该做的事情就是让他们放弃。从另外一个角度来说,发现你可以做到原本认为无法做到的事情,才是建立自信的最好方式。

市面上有很多图书,把亚洲母亲刻画成诡计多端、冷酷无情、残酷虐待的人,对自己孩子的真实兴趣漠不关心。对中国人来说,他们认为自己比西方人更关心孩子,愿意为孩子牺牲的更多,而西方人则得意洋洋地看着自己的孩子变坏。我觉得双方的观点都不正确,所有正常的父母都希望孩子变得最好,中国人只不过采取了不同的方式来实现这个目的。

西方父母试图尊重孩子的个性,鼓励他们去追求激情,支持他们的选择,提供正面的回应和有益的生活环境。而中国人认为保护孩子的最好方法是让他们准备好迎接未来,让他们了解自己的能力范围,用技能、工作习惯和内心的自信来武装他们。这些东西是谁也无法夺走的。

-Amy Chua是耶鲁法学院的教授。著有《帝国之日》和《世界大乱:自由市场民主输出是如何滋生了种族仇恨与全球动荡》。这篇文章是Amy Chua《猛虎母亲的战斗颂歌》一书的节选,即将由企鹅集团出版。

原文:

Can a regimen of no playdates, no TV, no computer games and hours of music practice create happy kids? And what happens when they fight back?.

Amy Chua with her daughters, Louisa and Sophia, at their home in New Haven, Conn.

A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids. They wonder what these parents do to produce so many math whizzes and music prodigies, what it's like inside the family, and whether they could do it too. Well, I can tell them, because I've done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do:

• attend a sleepover

• have a playdate

• be in a school play

• complain about not being in a school play

• watch TV or play computer games

• choose their own extracurricular activities

• get any grade less than an A

• not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama

• play any instrument other than the piano or violin

• not play the piano or violin.

I'm using the term "Chinese mother" loosely. I know some Korean, Indian, Jamaican, Irish and Ghanaian parents who qualify too. Conversely, I know some mothers of Chinese heritage, almost always born in the West, who are not Chinese mothers, by choice or otherwise. I'm also using the term "Western parents" loosely. Western parents come in all varieties.

All the same, even when Western parents think they're being strict, they usually don't come close to being Chinese mothers. For example, my Western friends who consider themselves strict make their children practice their instruments 30 minutes every day. An hour at most. For a Chinese mother, the first hour is the easy part. It's hours two and three that get tough.

Despite our squeamishness about cultural stereotypes, there are tons of studies out there showing marked and quantifiable differences between Chinese and Westerners when it comes to parenting. In one study of 50 Western American mothers and 48 Chinese immigrant mothers, almost 70% of the Western mothers said either that "stressing academic success is not good for children" or that "parents need to foster the idea that learning is fun." By contrast, roughly 0% of the Chinese mothers felt the same way. Instead, the vast majority of the Chinese mothers said that they believe their children can be "the best" students, that "academic achievement reflects successful parenting," and that if children did not excel at school then there was "a problem" and parents "were not doing their job." Other studies indicate that compared to Western parents, Chinese parents spend approximately 10 times as long every day drilling academic activities with their children. By contrast, Western kids are more likely to participate in sports teams.

What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you're good at it. To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences. This often requires fortitude on the part of the parents because the child will resist; things are always hardest at the beginning, which is where Western parents tend to give up. But if done properly, the Chinese strategy produces a virtuous circle. Tenacious practice, practice, practice is crucial for excellence; rote repetition is underrated in America. Once a child starts to excel at something—whether it's math, piano, pitching or ballet—he or she gets praise, admiration and satisfaction. This builds confidence and makes the once not-fun activity fun. This in turn makes it easier for the parent to get the child to work even more.

Chinese parents can get away with things that Western parents can't. Once when I was young—maybe more than once—when I was extremely disrespectful to my mother, my father angrily called me "garbage" in our native Hokkien dialect. It worked really well. I felt terrible and deeply ashamed of what I had done. But it didn't damage my self-esteem or anything like that. I knew exactly how highly he thought of me. I didn't actually think I was worthless or feel like a piece of garbage.

From Ms. Chua's album: 'Mean me with Lulu in hotel room... with score taped to TV!'

As an adult, I once did the same thing to Sophia, calling her garbage in English when she acted extremely disrespectfully toward me. When I mentioned that I had done this at a dinner party, I was immediately ostracized. One guest named Marcy got so upset she broke down in tears and had to leave early. My friend Susan, the host, tried to rehabilitate me with the remaining guests.

The fact is that Chinese parents can do things that would seem unimaginable—even legally actionable—to Westerners. Chinese mothers can say to their daughters, "Hey fatty—lose some weight." By contrast, Western parents have to tiptoe around the issue, talking in terms of "health" and never ever mentioning the f-word, and their kids still end up in therapy for eating disorders and negative self-image. (I also once heard a Western father toast his adult daughter by calling her "beautiful and incredibly competent." She later told me that made her feel like garbage.)

Chinese parents can order their kids to get straight As. Western parents can only ask their kids to try their best. Chinese parents can say, "You're lazy. All your classmates are getting ahead of you." By contrast, Western parents have to struggle with their own conflicted feelings about achievement, and try to persuade themselves that they're not disappointed about how their kids turned out.

I've thought long and hard about how Chinese parents can get away with what they do. I think there are three big differences between the Chinese and Western parental mind-sets.

Newborn Amy Chua in her mother's arms, a year after her parents arrived in the U.S.

.

First, I've noticed that Western parents are extremely anxious about their children's self-esteem. They worry about how their children will feel if they fail at something, and they constantly try to reassure their children about how good they are notwithstanding a mediocre performance on a test or at a recital. In other words, Western parents are concerned about their children's psyches. Chinese parents aren't. They assume strength, not fragility, and as a result they behave very differently.

For example, if a child comes home with an A-minus on a test, a Western parent will most likely praise the child. The Chinese mother will gasp in horror and ask what went wrong. If the child comes home with a B on the test, some Western parents will still praise the child. Other Western parents will sit their child down and express disapproval, but they will be careful not to make their child feel inadequate or insecure, and they will not call their child "stupid," "worthless" or "a disgrace." Privately, the Western parents may worry that their child does not test well or have aptitude in the subject or that there is something wrong with the curriculum and possibly the whole school. If the child's grades do not improve, they may eventually schedule a meeting with the school principal to challenge the way the subject is being taught or to call into question the teacher's credentials.

If a Chinese child gets a B—which would never happen—there would first be a screaming, hair-tearing explosion. The devastated Chinese mother would then get dozens, maybe hundreds of practice tests and work through them with her child for as long as it takes to get the grade up to an A.

Chinese parents demand perfect grades because they believe that their child can get them. If their child doesn't get them, the Chinese parent assumes it's because the child didn't work hard enough. That's why the solution to substandard performance is always to excoriate, punish and shame the child. The Chinese parent believes that their child will be strong enough to take the shaming and to improve from it. (And when Chinese kids do excel, there is plenty of ego-inflating parental praise lavished in the privacy of the home.)

Sophia playing at Carnegie Hall in 2007.

Second, Chinese parents believe that their kids owe them everything. The reason for this is a little unclear, but it's probably a combination of Confucian filial piety and the fact that the parents have sacrificed and done so much for their children. (And it's true that Chinese mothers get in the trenches, putting in long grueling hours personally tutoring, training, interrogating and spying on their kids.) Anyway, the understanding is that Chinese children must spend their lives repaying their parents by obeying them and making them proud.

By contrast, I don't think most Westerners have the same view of children being permanently indebted to their parents. My husband, Jed, actually has the opposite view. "Children don't choose their parents," he once said to me. "They don't even choose to be born. It's parents who foist life on their kids, so it's the parents' responsibility to provide for them. Kids don't owe their parents anything. Their duty will be to their own kids." This strikes me as a terrible deal for the Western parent.

Third, Chinese parents believe that they know what is best for their children and therefore override all of their children's own desires and preferences. That's why Chinese daughters can't have boyfriends in high school and why Chinese kids can't go to sleepaway camp. It's also why no Chinese kid would ever dare say to their mother, "I got a part in the school play! I'm Villager Number Six. I'll have to stay after school for rehearsal every day from 3:00 to 7:00, and I'll also need a ride on weekends." God help any Chinese kid who tried that one.

Don't get me wrong: It's not that Chinese parents don't care about their children. Just the opposite. They would give up anything for their children. It's just an entirely different parenting model.

Here's a story in favor of coercion, Chinese-style. Lulu was about 7, still playing two instruments, and working on a piano piece called "The Little White Donkey" by the French composer Jacques Ibert. The piece is really cute—you can just imagine a little donkey ambling along a country road with its master—but it's also incredibly difficult for young players because the two hands have to keep schizophrenically different rhythms.

Lulu couldn't do it. We worked on it nonstop for a week, drilling each of her hands separately, over and over. But whenever we tried putting the hands together, one always morphed into the other, and everything fell apart. Finally, the day before her lesson, Lulu announced in exasperation that she was giving up and stomped off.

"Get back to the piano now," I ordered.

"You can't make me."

"Oh yes, I can."

Back at the piano, Lulu made me pay. She punched, thrashed and kicked. She grabbed the music score and tore it to shreds. I taped the score back together and encased it in a plastic shield so that it could never be destroyed again. Then I hauled Lulu's dollhouse to the car and told her I'd donate it to the Salvation Army piece by piece if she didn't have "The Little White Donkey" perfect by the next day. When Lulu said, "I thought you were going to the Salvation Army, why are you still here?" I threatened her with no lunch, no dinner, no Christmas or Hanukkah presents, no birthday parties for two, three, four years. When she still kept playing it wrong, I told her she was purposely working herself into a frenzy because she was secretly afraid she couldn't do it. I told her to stop being lazy, cowardly, self-indulgent and pathetic.

Jed took me aside. He told me to stop insulting Lulu—which I wasn't even doing, I was just motivating her—and that he didn't think threatening Lulu was helpful. Also, he said, maybe Lulu really just couldn't do the technique—perhaps she didn't have the coordination yet—had I considered that possibility?

"You just don't believe in her," I accused.

"That's ridiculous," Jed said scornfully. "Of course I do."

"Sophia could play the piece when she was this age."

"But Lulu and Sophia are different people," Jed pointed out.

"Oh no, not this," I said, rolling my eyes. "Everyone is special in their special own way," I mimicked sarcastically. "Even losers are special in their own special way. Well don't worry, you don't have to lift a finger. I'm willing to put in as long as it takes, and I'm happy to be the one hated. And you can be the one they adore because you make them pancakes and take them to Yankees games."

I rolled up my sleeves and went back to Lulu. I used every weapon and tactic I could think of. We worked right through dinner into the night, and I wouldn't let Lulu get up, not for water, not even to go to the bathroom. The house became a war zone, and I lost my voice yelling, but still there seemed to be only negative progress, and even I began to have doubts.

Then, out of the blue, Lulu did it. Her hands suddenly came together—her right and left hands each doing their own imperturbable thing—just like that.

Lulu realized it the same time I did. I held my breath. She tried it tentatively again. Then she played it more confidently and faster, and still the rhythm held. A moment later, she was beaming.

"Mommy, look—it's easy!" After that, she wanted to play the piece over and over and wouldn't leave the piano. That night, she came to sleep in my bed, and we snuggled and hugged, cracking each other up. When she performed "The Little White Donkey" at a recital a few weeks later, parents came up to me and said, "What a perfect piece for Lulu—it's so spunky and so her."

Even Jed gave me credit for that one. Western parents worry a lot about their children's self-esteem. But as a parent, one of the worst things you can do for your child's self-esteem is to let them give up. On the flip side, there's nothing better for building confidence than learning you can do something you thought you couldn't.

There are all these new books out there portraying Asian mothers as scheming, callous, overdriven people indifferent to their kids' true interests. For their part, many Chinese secretly believe that they care more about their children and are willing to sacrifice much more for them than Westerners, who seem perfectly content to let their children turn out badly. I think it's a misunderstanding on both sides. All decent parents want to do what's best for their children. The Chinese just have a totally different idea of how to do that.

Western parents try to respect their children's individuality, encouraging them to pursue their true passions, supporting their choices, and providing positive reinforcement and a nurturing environment. By contrast, the Chinese believe that the best way to protect their children is by preparing them for the future, letting them see what they're capable of, and arming them with skills, work habits and inner confidence that no one can ever take away.

—Amy Chua is a professor at Yale Law School and author of "Day of Empire" and "World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability." This essay is excerpted from "Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother" by Amy Chua, to be published Tuesday by the Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Amy Chua. |