|

|

【原文标题】Exile meets homeland: politics, performance, and authenticity in the Tibetan diaspora

【原文作者】Emily T Yeh(叶蓓,美国科罗拉多大学地理系)

【登载媒体】Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2007, volume 25, pages 648 - 667

【来源地址】http://spot.colorado.edu/~yehe/society%20and%20space.pdf

【声明】本译文供Anti-CNN网站使用,未经译者和网站同意请勿转载,谢谢!

【编译校对】政治不正确、墨羽、音乐盒、忧心、rlsrls08、rhapsody

【译者前言】本文系学术论文,由于译者水平有限,译文难免出现错漏,望有识者指正,谢谢!

叶蓓,是一位美籍台湾人,嫁了给一位流亡印度藏人。她精通汉、藏、英三语。她这篇论文以详实的事例举证,客观的分析,指出海外的藏独运动只是人为地制造了西藏,印度与美国不同地方藏人文化的割裂。事实上藏人对什么为藏族文化的定义都很模糊,三地的藏族文化都在受到外来的影响不断地演化中。海外藏独运动把文化发展政治化,不仅不利于藏文化的发展,而且使藏人不能享受文化应该给他们带来的乐趣。

政治不正确 发表于 2009-3-23 02:19

叶蓓

【摘要·译文】

Tibetans are often imagined as authentic, pure, and geographically undifferentiated, but Tibetan identity formation is, in fact, varied and deeply inflected by national location and transnational trajectories. In this paper I examine the frictions of encounter between three groups of Tibetans who arrived in the USA around the same time, but who differ in their relationships to the homeland. The numerically dominant group consists of refugees who left Tibet in 1959 and of exiles born in South Asia; second are Tibetans who left Tibet after the 1980s for India and Nepal; and third are those whose routes have taken them from Tibet directly to the United States. Whereas the cultural authority claimed by long-term exiles derives from the notion of preserving tradition outside of Tibet, that of Tibetans from Tibet is based on their embodied knowledge of the actual place of the homeland. Their struggles over authenticity, which play out in everyday practices such as language use and embodied reactions to staged performances of 'traditional culture', call for an understanding of diaspora without guarantees. In this paper I use habitus as an analytic for exploring the ways in which identity is inscribed on and read off of bodies, and the political stakes of everyday practices that produce fractures and fault lines.

藏族常常被想象成正统﹑纯粹,和毫无地区差异的。但事实上,藏族身份的形成是多样化的,并且深受国家区位以及跨国轨迹的影响。本文将探讨生活在美国的三个不同藏族群体交往中发生的摩擦。他们几乎在同一个时期来到美国,但他们与家乡存在着不同的联系。人数上占主导地位的一个群体是那些1959年逃亡或者出生在南亚的流亡者;第二群是在上世纪80年代离开西藏前往印度和尼泊尔的藏人;第三群是那些直接从西藏来到美国的藏人。长期流亡藏人宣称的文化权威源于在西藏境外保存传统的信念,而本土藏人的文化权威却是基于其对家乡这一实际地方的具体认知。藏族侨民团体间对于“正统”的争议,从语言运用和具体反应等日常活动,到传统文化表演,都有待研究。本文用”惯习”(habitus)作为分析方法,探讨民族身份是如何形成的,又是如何体现的,以及对日常行为的政治划分是如何造成分裂与断层的。

"Oil and water cannot mix

Tibetans and Chinese cannot mix ...

We are Buddhists

You are its destroyers

We are yak meat-eaters

You are dog meat-eaters

We are tsampa-eaters

You are worm-eaters"

Red Chinese Robber Gang by Techung, a California-based Tibetan artist

“油水不可交溶

藏汉不可交溶

我们信仰佛教

你们将其破坏

我们吃牦牛

你们吃狗肉

我们吃糌粑

你们吃虫子”

——《红色匪帮》,加州藏族艺术家德琼

【正文·译文】

一个侨民的故事 (A diasporic story)

In February 2004 the board of directors of a regional Tibetan Association received an anonymous letter, written in bright red capital letters, accusing one of its members of "faxing documents to the Chinese government" about Tibetans in the USA, and of receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars for his 'spying' activities. The accused, who I will call Tenzin, is a Tibetan man in his mid-thirties. Raised in a village in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, he fled to India after participating in Tibetan independence protests in the late 1980s. Not long after arriving in Dharasmala, India, seat of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government in exile, he was picked by lottery to participate in the Tibet US Resettlement Project. In the USA he has been actively involved in the local Tibetan community. He also communicates regularly by telephone with family and friends in Tibet, remaining up to date on the latest trends in music and the changing economy of his home village.

2004年2月,一个地方的藏族协会的理事会收到一封用红色大写字母写的匿名信,举报其中一个会员把关于在美藏人的文件传真给中国政府,并且凭这些间谍活动得到数十万美元的收入。被告发的是一个35岁左右的藏人,笔者将称他为丹增。他出生在中国西藏自治区的一个村庄,在80年代末参加了争取西藏独立示威后逃亡到印度。到达兰萨拉(达赖喇嘛和西藏流亡政府所在地)不久后,他获抽签选中参加“藏人定居美国计划”。他在美国积极加入到当地藏族社区,也经常电话联系仍在西藏的家人和朋友,了解最新的音乐潮流和老家村庄的经济变化。

Despite having been naturalized as a US citizen, Tenzin has not returned to Tibet because of lingering fear for his family members and because of the fact that they have already been made to suffer for his actions; one brother was jailed for six years. When I met his elderly mother in Tibet, she pleaded, "please, tell him not to come back for another couple of years at least" even though she longed to see her son after a separation of more than a decade. The family's experience is both tragic and exemplary of the type of political repression to which the transnational Tibet Movement has called attention. The fact that he is a political refugee, together with his dedication to improving conditions in Tibet, suggest that Tenzin should be a poster child for the Tibet Movement, held out by the community as a model for others. Why, then, has he instead been suspected and accused (more than once) of being a spy for China?

尽管丹增已归化为美国公民,但出于难以挥去的对家人的担忧,他还没有回过西藏;他的家人们确实也因为他的活动而受苦,他的一个兄弟就坐了六年牢。当笔者在西藏见到他年迈的母亲时,虽然她很想见到分别十多年的儿子,但仍然恳求道:“请你告诉他别要回来,至少要等多几年”。这个家庭的经历既是一个悲剧,也是一个跨国西藏运动要唤起世人注意的政治压迫的典型案例。丹增作为政治难民的事实以及他对改善西藏状况的努力表明他应该是西藏运动的一个模范,被社区当作典型来进行宣传。那么为什么恰恰相反,他(不止一次地)被怀疑及指控为中国间谍?

Significantly, Tenzin is one of the very few Tibetans in the area to have spent a good part of his life in Tibet, rather than in India or Nepal. To at least a few Tibetans from India, the fact that he is from Tibet, is very active in the local organization, and has at times refused to have his photograph posted on community websites is 'proof ' enough that he is a spy. More generally, his strong ties to the homeland, and the way the homeland is inscribed on his body, make him the object of derision and suspicion.

值得注意的是,在当地社区中,丹增是为数不多的在西藏本土而不是在印度或尼泊尔渡过大部分人生的藏人。至少对于一部分从印度来的藏人来说,他来自西藏、在当地组织非常活跃、有时拒绝把他的相片放在社区网站上,这些事实已经足够“证明”,他是一个间谍。更广泛地来说,他与家乡的紧密联系,以及他身上所铭刻的那种家乡的印记都使得他成为一个被嘲笑与怀疑的对象。

Migrants' stories have theoretical power beyond their own uniqueness. Tenzin's story alerts us to some of the political and cultural contradictions of the Tibetan diaspora which emerge around the issues of migrants' roots and routes. Like other groups of transnational immigrants, Tibetans in the USA"forge and sustain multistranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement". Yet the structure of Tibetan immigration to the USA is such that the 'society of origin' to which the vast majority of Tibetans have immediate ties is in South Asia, not in Tibet. Tibetan immigrants in the USA can be divided into three groups vis-à-vis their embodied experience of Tibet and their immediate society of origin. First, the largest group is comprised of those who either left Tibet in 1959 or were born in South Asian refugee communities: for convenience, I refer to them here as 'exile Tibetans'. Second, a smaller number, who I refer to as 'new arrivals', were born and raised in Tibet, but left for India or Nepal in the 1980s and 1990s. Third, the smallest group are those whose routes have taken them directly from Tibet to the United States; I call them 'Tibetans from Tibet'.

移民的故事具有超越其自身独特性的理论性力量。丹增的故事提醒我们注意一些由移民的原籍和路线的不同而在藏族侨区引起的政治上和文化上的矛盾。与其它跨国移民群体一样,在美国的藏人也“形成并维系着千丝万缕的社会关系,这些关系联结着他们的原居地社群和移居地社群”。然而移居美国藏人的构成现况是这样:对大部分藏人来说,“原居地社群”最直接指向的地方是南亚而不是西藏。根据他们的原居地社群和体现的西藏经历,在美国的藏族移民可以分为三组:第一组,也是最大的一组由1959年离开西藏或者出生在南亚的难民社区难民组成,为方便起见,我把他们称为“流亡藏人”;第二组是人数较少的一组,我称他们为“新来者”,他们在西藏出生和长大,但在上世纪八九十年代前往印度或尼泊尔;第三组是人数最少的一组,是那些直接从西藏来到美国的藏族人,我把他们称为“本土藏人”。

In this paper I examine struggles over the authenticity of everyday embodied practices as well as of staged performances of 'Tibetan culture', which fracture the imagined unity of a seamless diasporic community. Marked as 'Tibetan' in distinct ways by the varied national locations through which they have traveled, Tibetans also draw on different strategies for establishing their authority to speak as Tibetan. Tibetans from Tibet draw on the embodied knowledge and experience of homeland, whereas 'exile Tibetans' seek to recenter authentic Tibet-ness away from the physical territory of the homeland and toward other geographical spaces - particularly Dharamsala. Exile Tibetans are numerically dominant in the USA, and it is their views that set the discursive terrain. However, their authority is challenged by the Tibetans from Tibet whom they encounter. The project of recentering the locus of authenticity is thus unstable, and requires an enormous amount of everyday cultural work.

本文将探讨关于日常生活中以及舞台表演的“藏族文化”正统性的冲突,这些冲突撕破了藏族侨区看似天衣无缝的和谐幻像。虽同为“藏族”,但经由不同的国家地区迁居而来的藏人群体,都在运用不同的策略来争取让自己成为权威的藏族发言人。本土藏人倚仗的是他们对家乡的具体认知和经验。相反的,流亡藏人寻求把“正统藏族”重新定位,由地理上的传统家园转移到其它区域,尤其是达兰萨拉。在美国,流亡藏人在数量上居主导地位,这种不着边际的地理定位也正是他们的观点所在。但是他们的权威受到了本土藏人的挑战。因而正统性地理中心的重新定位这一课题是不牢靠的,需要进行大量的日常文化工作。

侨居、身份与惯习 (Diaspora, identity, and habitus)

Responding to celebrations of diaspora and of border crossings as metaphors of emancipation, transgression, and subversion, critical geographers have suggested rethinking diaspora as being 'without guarantees', to borrow from Hall. That is, a diasporic condition may indeed be subversive or transgressive, but it is not necessarily so. Furthermore, diasporic identities and communities are always multiple and contested. All of this is quite evident in the lyrics of Red China Robber Gang by Techung, a popular California-based Tibetan singer. In exuding a sense of defiance and pride in Tibetan identity, the song also plays directly into existing Western stereotypes of Chinese as alien, dog-eating, and/or Communist Others. This demonization of the Chinese is often extended by Tibetans reared in South Asia to Tibetans who have grown up in Tibet - who are suspected of being 'brainwashed' by China.

对于把藏族侨区和跨越国境宣扬为解放、抵制和反抗的象征,地理批评家主张重新审视藏族侨区,为“缺乏理据”的——一个引自霍尔的词汇。也就是说,侨区状况可能真的具有颠覆性或进攻性,但不是非得如此。此外,侨民身份和侨民群体一直是多样化及具争议性的。由加州藏族流行歌手德琼创作的《红色中国匪帮》的歌词是其中一个很好的例证,除了流露出(对汉族的)蔑视以及对藏族身份的自豪感外,这首歌直截了当地附和了西方对中国人的刻板印象:怪异、吃狗肉以及共产党异类。在南亚长大的藏人经常把对中国人的妖魔化扩大至在西藏长大的藏人,怀疑他们已经被中国洗脑。

The need to recognize that a diasporic condition is not always already politically progressive is acute in the Tibetan case, because of the way in which the diasporic struggle has been structured by the Cold War and by the conflation of Chinese-ness with Communism. The CIA's covert support for the Tibetan resistance army, Chushi Gangdrug, from 1956 until 1972 grew directly out of the Cold War project to contain Communism. These geopolitical entangle- ments have made for strange political bedfellows; former Republican Senator Jesse Helms, known for his distaste for what he called "Red China" and the "barbarous, Communist Chinese government", was one of the earliest and most vocal supporters of the Tibetan cause in the US government. In an ironic twist, perfor- mances in the 1970s by the Dharamsala-based Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts were heckled vociferously by audiences in Washington DC, Madison, and Berkeley, who were ideologically supportive of, if not well-informed about, the Communist project in China. The partial structuring of the internal politics of Tibetan communities by this field of global geopolitics makes their dynamics all the more important to tease apart.

认识到侨区状况在政治上不一定总是进步的,对西藏运动至关重要,因为流亡藏人的抗争方法跟冷战以及中国特色与共产主义的结合息息相关。中央情报局从1956年到1972年间对四水六岗藏人抵抗军队的秘密援助,完全是出于遏制共产主义的冷战策略。这些地缘政治上的瓜葛造就了政治上的临时伙伴;以憎恶中国并称之为“红色中国”、“野蛮的中国共产党政府”而闻名的前共和党参议员杰西·赫尔姆斯,是美国政府中最早和最强烈的西藏运动支持者之一。一个啼笑皆非的插曲是,上世纪七十年代,达兰萨拉藏族表演艺术学院的演出常常被华盛顿、麦迪逊和伯克利的观众喝倒彩,他们在意识形态上支持中国共产党,尽管不甚了解。藏族群体内部的党派政治斗争在世界地缘政治的大气候中得到了加强而不是分裂。

Of course, Tibetan communities have always been cross cut by multiple identities. Nevertheless, practices such as long-distance trade and pilgrimage gave a relative coherence to Tibetan cultural identity, including a sense of shared history, a common literary language, aspects of genealogy, myth, and religion, and folkloric notions such as Tibetans as eaters of tsampa (ground barley flour). However, the 'imagined community' of Tibet as a nation and the belief that Tibetans should thus have a unique nation-state, emerged strongly only in the early 20th century, after the 13th Dalai Lama fled to India and then to Mongolia after British and Chinese invasions, and especially after the 1951 incorporation of Tibet into the People's Republic of China (PRC).

当然,藏人群体一直为各种各样的身份特征所切割。尽管如此,长途贸易和朝圣等活动使藏族文化具有了特征相对的连贯性,包括共同的历史、共同的书面语言、血缘联系、神话和宗教,还有比如藏族吃糌粑(青稞粉)的民俗概念。然而,到了二十世纪初期,在十三世达赖喇嘛因为英国和中国的侵略而逃亡到印度再前往蒙古,尤其是1951年西藏并入中华人民共和国后,把藏族群体想象成一个国家,并且认为藏人应该有一个单一民族的国家的信念强烈地凸显了出来。

Prior to this century, Tibetans conceived of themselves primarily in relation to sectarian and regional affiliations. Thus, the term Bod-pa, now a general term for 'Tibetan', was used only in reference to nonnomadic inhabitants of Central Tibet. Even in the 1970s the Tibetan government in exile worked hard to forge a national Tibetan identity to supercede divisive regional and sectarian identifications. In exile communities today there are still undercurrents of regional divisiveness, but, like the 'Kham for the Khampas' movements of the 1930s and the history of the Kham-oriented Chushi Gangdrug resistance movement (McGranahan, 2005), they are largely papered over in the transnational nation-building project of the Tibetan government in exile and of the Tibet Movement. Tibetans in exile insist today that, "For more than two thousand years, Tibet ... existed as a sovereign nation". As Renan has observed, "To forget and ... to get one's history wrong, are essential factors in the making of a nation."

在二十世纪以前,藏人对自身的认识主要是宗派和区域的隶属关系。因此,bod-pa,也就是现在的"藏人(Tibetan)"这个词,仅仅指生活在西藏中部的非游牧民。甚至到了上世纪七十年代的时候,西藏流亡政府还在致力锻造一个全民族的藏族特性,来取代地区性和宗派性的身份认同。直至现在流亡藏人群体内仍涌动着地区派系的暗潮,例如三十年代的“康巴人的康区”运动和起源于康区的四水六岗抵抗运动。但这些历史大体上被西藏流亡政府和西藏运动的跨国建国计划隐瞒了。如今的流亡藏人坚称:“在超过二千年的时间里,西藏一直是一个主权国家”。正如Renan评论道的那样:“忘记……或者错误地理解历史,是编造一个国家的必要因素。”

In addition to regional affiliation, axes of identification that were socially relevant both in the 1950s and today (in diaspora as well as in Tibet) include gender, age, class, and social status (aristocrats and commoners), religious and sectarian affiliation, and the lay-monastic divide. However, these differ from the contestation of identities that are the specific focus of this paper: the varying routes to the US diaspora through different national locations, and the consequent forms of identification with homeland. The latter are the product of the diasporic process itself, and thus constitute a newly formed axis of struggle and consent. This axis is not, however, independent of other axes of identification, particularly that of region, as I discuss below. Though these distinctions are relatively new and are not as formalized in linguistic categories as are other types of identifications, they are nevertheless social facts that permeate everyday practices and struggles around recognition.

无论是五十年代还是在今天(包括流亡聚居地和西藏),民族特征组成的基准除了区域隶属之外,在社会关系上还包括:性别、年龄、阶级与社会地位(贵族与平民)、宗教和派系从属,以及教徒与僧侣的区别。但是这些都与本文所专注讨论的民族特征不同:从不同的居住地经由不同的路线前往美国侨居,和由此形成的对家园的认定。后者是侨居过程的自身产物,由此构成了新的争论与认同的基准。但这一基准并不是独立于其它民族特征之外的,特别是我将在下面讨论的区域性特征。虽然这些差异性相对来说比较新,并且不像其它特征那样有一个正式的名称,但它们却渗透到日常活动中并寻求认同。

The importance of everyday practice, and the ways in which the 'authenticity' of Tibetan identities is both inscribed on and read off of bodies, suggests habitus as a productive analytical frame. Bourdieu emphasizes that habitus is a set of 'durable dispositions', a kind of historical sedimentation in and of the body: "The habitus, a product of history, produces individual and collective practices ... it ensures the active presence of past experiences which, deposited in each organism in the form of schemes of perception, thought and action, tend to guarantee the 'correctness' of practices and their constancy over time, more reliably than all formal rules and explicit norms". Habitus mediates between places and selves; it is the way in which bodies bear traces of the places in which they have dwelled. Casey describes these traces as being "continually laid down in the body, sedimenting themselves there and thus becoming formative of its specific somatography."

日常活动的重要性,以及所谓的“正统”藏族身份形成和表现于个体的方式,说明“惯习”是一个有效的分析框架。布尔迪厄强调,惯习是一系列“持久的习性”,一种历史的沉淀,它作用于机体又由其表现出来:“惯习是历史的产物,产生个体和集体的实践活动……它确保既往经验的有效存在,这些既往经验以感知、思维和行为图式储存在每个人身上,与各种形式规则和明确的规范相比,能更加可靠地保证实践活动的一致性和它们历时而不变的特性。”惯习作用于场所与自身之间;个体透过这种方式表现出它栖身过的场所的痕迹。凯西将这些痕迹描述为“持久地潜藏并自我沉降于个体里,且由此成为其自我生发的形成要素”。

Despite the remarkable influence that this concept has had on contemporary understandings of culture and society in critical human geography, habitus has been relatively neglected in geographical studies of diaspora and transnationalism. However, Kelly and Lusis write that "the habitus of Filipino immigrants is constructed not just within a geographically contiguous space, but also through transnational linkages with their place of origin", a useful observation for understanding how Tibetan immigrants, who imagine that they should share a set of unique and recognizable characteristics with all other Tibetans, nevertheless have divergent embodied, durable dispositions, constructed through transnational linkages with different national locations. The variations in habitus encounter the expectation of similarity and recognizability, leading to the frictions explored here.

“惯习”的概念显著影响了当代人文地理学中对文化和社会的认识,然而在对侨居和跨国现象的地理学研究中,它相对而言被忽略了。然而,凯莉和露西斯写道“菲律宾移民的惯习不仅形成于地理学的邻近空间中,还通过他们与原居地的跨国关联”,这一观察有助于理解藏族移民的思维。藏族移民设想所有藏人应该具有共同的独特性和易于辩认的特征,但他们有通过不同民族区域的跨国关联而形成的不同的持久习性。当惯习的变更与相似和易辨的预期相遇时,就产生了本文所要探讨的摩擦。

Sedimentations in the body include the deployment of particular languages and of words within a language, as well as taken-for-granted dispositions such as intonation, gestures, and 'taste', appreciation for or reaction against particular styles, such as of dress, food, and staged performances of 'authentic' song and dance. Habitus is durable, but not eternal. As a sedimentation of past determinations it has a certain inertia which confers "upon practices their relative autonomy with respect to the external determinations of the immediate present". On the other hand, change - within limits of continuity - can occur through a dialectical confrontation between habitus and social field; this happens when "dispositions encounter conditions (including fields) different from those in which they were constructed and assembled", such as in a rapidly changing society. This describes the Tibetan diaspora in the USA, in which the habitus of Tibetans from Tibet, of Tibetans from exile, and of those who have experienced both are unmoored from their social fields and places of sedimentation and encounter each other. Thus, I do not argue in what follows that the community fractures described here are fixed forever, but rather try to capture the present moment of confrontation and negotiation.

沉积在个体里的习性包括:特定语言的使用,和一种语言中特定词汇的运用,自然而然的腔调、势态和“品味”,对特定风格的好恶,比如衣着、饮食,还有舞台表演中的“正宗”歌舞。惯习是持久的,但不是永恒不变的。作为过往判断的沉积,惯习具有惯性,受制于当前的外部影响。另一方面,在保持有限的延续性的同时,惯习与社会环境也会辩证的对抗。这种情况发生在”习性遇到与之形成过程中完全不同的条件(包括场域)时”,比如一个急速变化着的社会。它描述了美国侨居藏人的状态,其中包括来自西藏的藏人、流亡藏人和那些兼具两处体验的藏人,他们离开了他们的社交场所和沉积惯习的地方,并遭遇彼此。因此,我不去争论本文所描述的群体断裂会以何种形式永久固定下来,而宁愿试着去捕捉当前这一对峙与妥协的瞬间。

After a brief overview of the Tibetan diaspora, I trace the experience of 'new arrivals' such as Tenzin from India to the USA. Next, I turn to two key arenas of struggle over authenticity: language choice and staged 'cultural' performances, includ- ing embodied reactions of appreciation or distaste for certain types of performances. Of importance here is not only the fact that dispositions, mannerisms, and apprecia- tion of style are different but that each set of dispositions is understood as the only way to be authentically Tibetan. After this I examine different strategies of establishing cultural authority, and, finally, look at the political stakes in seemingly inconsequential matters of taste.

在对侨居藏人作一番简要概述后,笔者会追踪“新来者”的经历,比如从印度来美国的丹增。接下来,会转而介绍正统之争的两个关键场所:语言选择和舞台“文化”表演,包括对某些表演形式的具体反应为欣赏或厌恶。重要的是,各方不仅仅性情、癖好和欣赏方式有所不同,而且都认为自己才是唯一的藏人正统。之后,笔者将审视建立文化权威的不同策略,最后会讨论在看似无足轻重的品味里所含的政治利害关系。

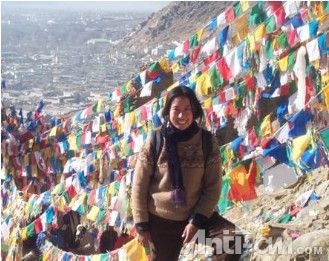

The multisited ethnography presented here draws upon participant observation and a series of semistructured interviews with Tibetans living in Lhasa, Tibet, northern California, and the Denver metro area of Colorado. By participant observation, I refer to attendance at picnics, meetings, parties, discussions, and performances, and visits in private homes. The approach is grounded in the understanding that "unearth[ing] what the group takes for granted" requires extensive interactions and familiarity with social setting. Interviews and unstructured conversations and interactions were conducted primarily in Tibetan, and, less frequently, in Chinese.

这里出现的多点民族志,借由参与观察法和一系列对藏人的半结构访谈来实现,被采访者居住在西藏拉萨、加利福尼亚州北部和科罗拉多州丹佛地区。我的参与观察法,指的是出席(藏人的)野餐、会议、聚会、讨论、表演和到私人家里拜访。此方式建立的基础,是发掘这一群体视之为理所当然之处需要广泛的互动和对社会情境的熟悉。访谈,随性的对话及互动主要以藏语进行,其次以汉语。

藏族侨区概况 (The Tibetan diaspora in brief)

After the failed uprising in Lhasa in 1959, roughly 80 000 Tibetans followed the 14th Dalai Lama to exile in South Asia. Some lived in towns such as Kathmandu, Delhi, Mussoorie, and Dharamsala, and others settled in agricultural and handicraft settlements established by the government in exile with the help of Western aid organizations. After the peak years of exodus from 1959 to 1961, the borders of Tibet were effectively closed. The political isolation of China meant that there was very little contact between Tibetans inside Tibet and the refugee community for more than two decades.

在1959年的拉萨暴动失败后,约8万名藏人随14世达赖喇嘛往南亚流亡。一些人住在加德满都、德里、马苏里和达兰萨拉等城镇,其他人定居在西方援助组织帮助流亡政府建立的农业和手工业定居区里。在1959至1961的出走高峰年份之后,西藏边境事实上被封锁了。中国的政治孤立意味着西藏境内的藏人和(境外流亡的)难民团体之间有二十多年是几近隔绝的。

Only after the death of Mao, the beginning of reform, and the then Chinese Party Secretary Hu Yaobang's fact-finding visit to Tibet in 1980 were restrictions somewhat loosened. In the early 1980s refugees were allowed to visit their relatives in Tibet if they applied for 'overseas Chinese' passports (many refused to do so). Between 1985 and 1988 some Tibetans were given permission to go on pilgrimage and to visit relatives in India, where many of them stayed. At the same time, parents began to send their children to schools in India to receive a Tibetan education.

只有到了毛泽东去世后,改革开始之际,以及当时的中共总书记胡耀邦1980年到西藏的实地考察之后,才使得限制稍微有所放松。上世纪八十年代早期,难民被允许到西藏探亲,如果他们申请“华侨”护照的话(许多人拒绝这么做)。在1985到1988年间,一些藏人获得许可去印度朝圣和探亲,许多人就在那儿呆了下来。同时,家长们开始将他们的孩子送到印度的学校以接受藏族教育。

However, the pro-independence demonstrations in Lhasa from 1987 to 1989 led to the imposition of martial law. Traveling legally to India became difficult once more, but the political crackdown that ensued produced another wave of Tibetans who fled to India. An estimated 2000 - 3000 Tibetans continue to leave illegally for India every year, though in recent years this has become increasingly difficult with the Chinese government's pressure on Nepal to arrest and forcibly repatriate Tibetans passing through to India. 'New arrivals' - as members of this second wave of Tibetans arriving in India are often referred to - are estimated to constitute more than 10% of the total diasporic population, which was estimated at 150 000 in 2002.

然而,1987到1989年间拉萨支持独立的示威致使政府实施戒严。合法前往印度再度变得困难,但接踵而来的政治镇压却在藏人中掀起了又一波逃往印度的浪潮。近年来,中国政府对尼泊尔施压要求逮捕和强制遣返经由尼泊尔入印度的藏人,又使情形随之变得日益困难,但据估计,每年仍有二到三千名藏人继续非法前往印度。这第二波抵达印度的藏人成员常常被称为“新来者”,据估计在2002年侨居藏人的15万总人口中占到了超过10%的比例。

The two major processes in the Tibetan diaspora of interest here are, first, the arrival of this second wave of refugees from Tibet after 1985; and, second, the large-scale movement of Tibetans from South Asia to the USA after the passage of the 1990 Immigration Act. Section 134 of the Act, the Tibetan US Resettlement Program (TUSRP), granted permanent resident status to 1000 Tibetans living in South Asia. These were chosen by quota according to categories, including 100 slots for 'new arrivals' from Tibet. Beginning in 1996 the lottery winners, who had been assigned to resettlement clusters in eighteen states, became eligible to bring their families to the USA.

侨居藏人的两大进程令人感兴趣,第一,1985年后这第二波来自西藏的难民的到来;第二,在《1990年移民法》通过后,藏人自南亚大举迁至美国。根据该法案第134章,藏人定居美国计划(下简称TUSRP),居住于南亚的1000名藏人被授予了(美国的)永久居留权。这些人是依照各类别配额被选中的,包括给来自西藏的“新来者”的100个名额。1996年开始采取抽签的办法,已被分配到18个州定居点的抽中者,可以将他们的家人带到美国。

A secondary effect of both the remittances that they began to send home and the heavy representation of Tibetan elites among the participants was the accumulation of social capital to the migrants. This has motivated and facilitated the migration of Tibetans from Nepal and India through non-TUSRP channels as well. The current estimate of 10 000 Tibetans in North America is far beyond what TUSRP had originally envisioned. Economically, there is intense pressure for remittances, and, symbolically, 'the West' has come to be seen in South Asian exile communities as a surrogate Shangri-la, diametrically opposed to China.

他们开始往家里汇款以及参与者中许多是藏族中的精英这两个因素产生了一个次生效应,即移民社会资本的积聚。这一效应同样诱使和便利了藏人通过非TUSRP渠道从尼泊尔和印度向外移民。当前估计有1万藏人生活在北美,已远远超过TUSRP的初始预想。在经济意义上,对汇款的需求相当迫切;而在象征意义上,“西方”已经成了在南亚的流亡团体眼中“香格里拉”的代名词,与中国一词截然相反 。

Increasingly, however, the USA has also become the destination of Tibetans who travel directly from Tibet. They are few in number, no more than a handful in all but the largest Tibetan communities (such as, New York or San Francisco). Though a few have rural origins and minimal educational background, the dominant pattern of their transnational migration is through channels that rely on extensive education in the PRC, which in turn favors urban backgrounds. Some were cadres or staff for the small but increasing number of foreign development projects in Tibet, who come to the USA as visitors, trainees, or students. Their numbers also include a few who had come under political suspicion in their work units in Tibet. The contentious politics of authenticity between the long-time exiles, the 'new arrivals', and the Tibetans from Tibet, in the USA, grows out of the earlier reception of 'new arrivals' in India, to which I turn next.

渐渐地,美国也成为了来自西藏的藏人的直接目的地。他们数量很少,零星地散布在各个藏人群体里,除却一些大型社区(比如,纽约或旧金山)。尽管有少数人出自农村,只受过基础教育,但他们跨国移民的主要方式是通过在中国受高等教育而得来的出国渠道,而城市的藏人更容易享有这种机会。西藏对外发展项目数量虽少却在日益增多,有些人是这些项目的干部或员工,他们到美国探访、培训或留学。一些在他们西藏的工作单位受到政治上的怀疑的人也在其中。在美国的长期流亡者、“新来者”,以及本土藏人间对于正统的争议政见,产生于接收来自印度的“新来者”的早期,接下来我会谈到这个。 |

侨居, 政治, 流亡, 演出, 藏族, 侨居, 政治, 流亡, 演出, 藏族, 侨居, 政治, 流亡, 演出, 藏族

|